By Sophie Theis, Ruth Meinzen-Dick, Agnes Quisumbing, and Chiara Kovarik on November 2, 2015

This post is part of the “Science on the Pulse” series - a two-part quarterly review on the latest literature on ecosystem services and on gender.

What are we actually talking about when we refer to women’s land rights?

In the lead up to the Global Landscapes Forum event, This land is our land: Perspectives on land access and restoration, Thrive asked the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) to share ten essential articles for gaining an understanding of the key issues in gender and land tenure.

Before you read ahead, please note that an investigation of the local context is always necessary. But here’s what the research is showing us. The following ten papers from IFPRI authors and partners highlight what we know and what we don’t know - but really should! - about gender and land tenure.

1. Gender, assets, and agricultural development: A conceptual framework by Meinzen-Dick, R. et al. (2011)

This article provides a great foundation for readers who want to better understand the significance of assets, including land. It also formed the basis for the Gender, Assets, and Agriculture Project.

The authors offer a conceptual framework to understand how men and women’s ability to access, control, and own productive assets such as land, livestock, finance, and social capital enables them to create stable and productive lives. Unlike previous frameworks, this model recognizes that men and women not only control, own, and dispose of assets in different ways, but also access, control, and own different kinds of assets. It also explicitly recognizes that some assets are held individually, and some jointly between household members.

2. Gender inequalities in ownership and control of land in Africa: myth and reality by Doss, C., et al. (2015)

Do women really own less than 2% of the world’s land? If you’ve heard this zombie statistic before, you’re not alone. These types of numbers continue to circulate in part because we do not have better data. However, in order to articulate specific policy responses to these inequalities, it is critical to fill these data gaps.

In this paper, the authors explore what the data actually say about the gender gap in ownership and control of land in Africa. They highlight the challenges to defining ownership: Does it require formalization and documentation? Does it imply rights to sell land? Who defines ownership? Answers to these questions depend in part on what development outcomes are expected from gender-equitable land “ownership” in the given context.

The authors do not find adequate evidence to create a single statistic on women’s land ownership for Africa, but they do find that across multiple measures in Africa – from reported landownership, documentation of ownership, operation, management, and decision making – there are wide gender gaps.

Read the study for recommendations on standardizing the collection of sex-disaggregated, individual-level land data.

3. Examining gender inequalities in land rights indicators in Asia by Kieran, C et al. (2015)

In a related piece to #2, Kieran et al. investigate the quality and coverage of data on men and women’s land rights in nationally-representative datasets from Bangladesh, Tajikistan, Vietnam, and Timor-Leste, the only four countries in Asia with adequate data to calculate the five recommended indicators from Doss et al. (2015) that provide a comprehensive picture of women’s land ownership. The authors find that women are consistently disadvantaged compared with men with respect to reported ownership, documented ownership, and plot size.

Available open access as an IFPRI discussion paper.

4. Who owns the land? Perspectives from rural Ugandans and implications for large-scale land acquisitions by Doss, C. et al. (2014)

In Uganda, although many households report husbands and wives as joint owners of the land, women are less likely to be listed on ownership documents, especially titles. Examining the wide array of land ownership definitions reveals that a simplistic focus on title to land misses much of the reality regarding land tenure and could especially have an adverse impact on women’s land rights.

Available open access as an IFPRI discussion paper.

5. The gender implications of large-scale land deals by Behrman, J. et al. (2012)

Our review would not be complete without mentioning large-scale land deals. Whether viewed as “land grabs” or as agricultural investments for development, key stakeholders have paid little attention to an important dimension of these deals that is essential to understanding their impact: gender.

The costs and benefits of these deals are likely to be experienced differently by different household members. The authors point out that the way land deals interact with existing land tenure situations can yield a range of impacts on women’s land rights.

The authors also highlight the risk that those with undocumented property rights, especially women, are likely to be left out of negotiations over land transactions, even when their livelihoods are affected.

6. Can government-allocated land contribute to food security? Intrahousehold analysis of West Bengal’s land titling program by Santos, F. et al. (2014)

What are the benefits when simple changes are made to land registration rules to account for gender? Santos et al. examine impacts of a joint land titling and allocation scheme implemented by the Government of West Bengal in India that promotes the inclusion of women’s names on land titles. They find that inclusion of women as co-owners leads to improved security of tenure, agricultural investments, and women’s involvement in food and agricultural decisions.

Available open access as an IFPRI discussion paper.

7. Land rights knowledge and conservation in rural Ethiopia: Mind the gender gap by Quisumbing, A. and Kumar, N. (2014)

Laws and regulations regarding land tenure are important but not sufficient to encourage investment behavior on land that improves gender equality and resilience. Even though Ethiopia implemented a highly successful gender-sensitive reform of land rights, gender gaps in knowledge about the reform limited women’s adoption of both soil conservation practices and the planting of tree crops and legumes.

In a related paper, Kumar and Quisumbing find that awareness of Ethiopia’s land registration program is positively correlated with a shift in support for the equal division of land and livestock upon divorce. However, women are less likely than men to be aware of the land registration process.

The policy implications are significant: legislation mandating equal property rights is only as effective as the extent to which people know the different dimensions of their rights. Accompanying measures to overcome gender gaps in access to information are therefore critical.

8. Filling the legal void? Experimental evidence from a community-based legal aid program for gender-equal land rights in Tanzania by Mueller, V. et al. (2015)

If not only land policies matter, but also women’s knowledge of their rights, what is needed to create this awareness?

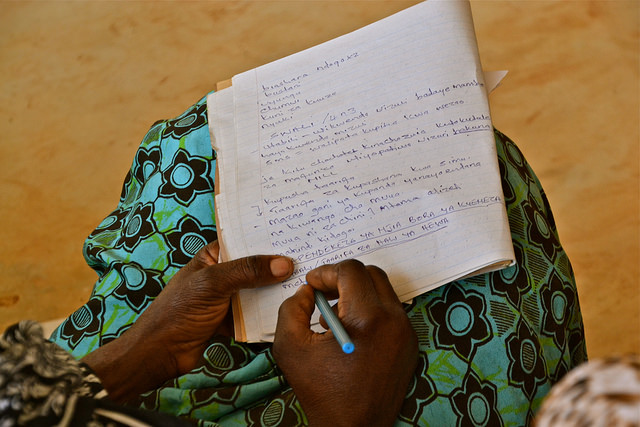

Community-based legal aid programs have been promoted as one way to expand access to justice for marginalized populations, through provision of free legal aid and education. The authors conduct one of the first rigorous evaluations of the impacts of such a program.

The authors find limited success in their evaluation of a short-term legal aid program in Tanzania, but note that altering strong social norms in favor of women’s land rights may require more time and resources to reach women.

9. Can integrated agriculture-nutrition programs change gender norms on land and asset ownership? Evidence from Burkina Faso by Van den Bold, M. et al. (2015)

Can gender norms surrounding land rights really change? Yes they can, suggests this study from Hellen Keller International’s homestead food production program in Burkina Faso, which made community land available to women through land leases, transferred small livestock to women, and taught women how to grow nutritious vegetables in their home gardens. Though men still own and control most assets, in treatment areas, women developed greater decision-making power and control over home gardens and their produce, and attitudes towards women owning property became more favorable.

10. Bargaining power and biofortification: The role of gender in adoption of orange sweet potato in Uganda by Gilligan, D. et al. (2014)

How do land rights affect decision making? It turns out that gender matters here too, but not exactly as you might expect. In Uganda, Gilligan et al. found that adoption of orange sweet potato, promoted as part of a strategy to reduce Vitamin A deficiency, is more likely on plots that are jointly owned by husband and wife, but where the wife has primary decision making on what to grow. Interestingly, plots of land exclusively controlled by women are not more likely to grow orange sweet potato, and plots exclusively controlled by men are least likely to contain orange sweet potato. These findings reflect the importance of joint ownership and how joint ownership is not equivalent to perfectly joint decision making.

So, what can we draw from these papers? Even though all existing evidence points towards large gender gaps in ownership and control over land, significant data shortcomings and substantial variations in definitions and implications of land rights make it difficult to generalize about land tenure situations, monitor progress, or formulate policy responses. These papers spotlight where evidence is needed to move forward.

Given the context-specific nature of gender relations and land tenure, it would be dangerous to apply a one-size-fits-all solution to closing gender gaps in land rights. However, it is clear that legal reforms alone are not enough: women and men need to be made aware of such changes. Ultimately, social norms need to change for more equitable distribution of property rights, and changes in these norms are possible.

Originally posted on the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystem blog Thrive.