By Marie Gagné, revised by Ibrahima Ka, Professional in charge of rural land tenure at the WAEMU Commission.

This is a translated version of the country profile originally written in French.

Senegal has the particularity of being the westernmost point of the African continent, which is located at the tip of Almadies in Dakar, the country's capital. With an area of 196,722 km2 , Senegal is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Mauritania to the north, Mali to the east and Guinea and Guinea-Bissau to the south. The Gambia, a country located on either side of the river bearing the same name, forms an enclave within Senegal. The relief of Senegal is generally flat and low, with an average altitude of less than 50 metres over three quarters of the territory.

The urbanization rate has increased from 34% in 1976 to 47.38% in 2021. Nevertheless, the majority of the population remains rural, with 52.62% living in the countryside.

Photo: Sylvain Cherkaoui/DFID/ECHO/ACF/Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

After Côte d'Ivoire, Senegal is the second largest economy in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) within the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU). Since the 1960s, the contribution of the agricultural, forestry and fisheries sectors to Senegal's GDP has been on a downward trend, but there has been an upturn since 2007. This rate will reach 17% in 20201.

Agricultural production, defined in the broadest sense (agriculture, arboriculture, fishing and livestock), represented the main income-generating activity for 49.5% of households in Senegal in 2013. The agricultural sector remains dominated by small family farms (less than 5 hectares for three quarters of households), which mostly practice rain-fed agriculture and, to a lesser extent, flood recession and irrigated crops. Livestock occupies 28.2% of Senegalese households and provides 55-75% of income in rural areas2. In 2017, the national livestock population numbered 17,865,881 head, mostly composed of sheep (39%), goats (33%) and cattle (20%)3.

In both urban and rural areas, land in this small country is highly coveted by domestic and foreign actors with diverse and even incompatible objectives. In addition to the demand for family and industrial agriculture, pastoralism, mining, infrastructure, tourism and housing, the pressure on land is amplified by population growth and soil degradation4.

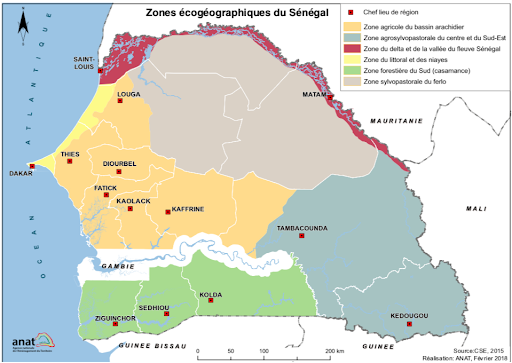

These land tenure issues differ according to the six eco-geographical zones in Senegal.

- The groundnut basin: This is an area where groundnut cultivation has been dominant since colonial times. This cultivation has led to massive deforestation and soil exhaustion, although the trend has been reversed since the 1980s with a reduction in cultivated areas and the regrowth of vegetation in the old fields. The groundnut basin also has a tradition of mining (phosphates, sand, clays and peat) in several open pits.

- The Senegal River Valley: located in the north of the country, this valley with an arid climate is crossed by the second largest river in West Africa, the Senegal River, which is 1,750 kilometres long. For a long time an area of recession agriculture on the alluvial plains,irrigated crops have been developing since the commissioning of the Diama and Manantali dams which control the flow of water. Animal husbandry is practised on the sandy uplands.

- The Niayes: these fertile lowlands along the maritime coast between Dakar and Saint-Louis are favourable to market gardening. However, droughts have led to a drop in the water table and salinization of the soil. Urbanisation, road infrastructure development and mining also threaten peri-urban agriculture.

- The sylvo-pastoral zone of the Ferlo: the main activity in this zone is extensive livestock farming. It is characterised by low rainfall, to which are added overgrazing and bush fires as factors degrading the woody potential.

- The sylvo-pastoral zone of the centre and south-east: often called Eastern Senegal, agriculture and livestock breeding are practised here, as well as the exploitation of the forest for the production of charcoal. The region of Kédougou is also rich in mining resources, especially gold.

- Casamance: This forested area with a tropical climate has seen an increase in temperature and rainfall in recent years. Rice cultivation in the lowlands is widespread, but is increasingly subject to salinity and acidity of the soil. Logging and bush fires are also reducing the forest cover5.

Source: CSE, 2015; development: ANAT, February 2018

Historical context

In Senegal, the colonial economy was largely based on the production and export of groundnuts, mainly under the aegis of religious leaders of the Mouride Muslim brotherhood. These religious leaders, known as marabouts, received from the French administration vast areas of land cultivated by their disciplines6. The colonial state also tried to create some experimental farms and irrigation schemes in the Senegal River valley.

After independence, the Senegalese government maintained these orientations and became actively involved in the supervision, financing and marketing of agricultural production. From the 1980s onwards, however, the agricultural sector experienced a decline, due to droughts affecting rainfed crops, the fall in world groundnut prices and structural adjustment policies that led to the disengagement of the state from the economy7.

Since the 2000s, there has been a renewed interest in the agricultural sector. President Abdoulaye Wade, who was in power from 2000 to 2012, established various programs to revive agriculture and develop biofuel production. In 2006, Wade set up the Plan Retour vers l'Agriculture (REVA Plan) to create integrated village farms as a means of containing illegal emigration to Europe. One of the components of the REVA Plan was the development of jatropha curcas cultivation8 at a rate of 1,000 hectares per rural community, for a total of 321,000 hectares throughout Senegal. Wade also established the Great Agricultural Offensive for Food and Abundance (GOANA) to increase local production of food and industrial crops. Combined with the triple food, financial and energy crisis of 2007-2008, these programmes contributed to a wave of large-scale land acquisitions by domestic and foreign investors.

President Macky Sall, elected in 2012 and re-elected in 2019, has largely continued these efforts in agricultural development. The main document currently guiding the government's policies is the Emerging Senegal Plan (ESP). The first strategic axis of this plan aims to achieve a "structural transformation of the economy" through the development of agriculture, social housing, tourism, industry and the mining sector, all areas of activity with a high land impact9.

Land legislation and regulations

In Senegal, access to land in rural areas is still governed by Law No. 64-46 of 17 June 1964 on the national domain. Originally, the post-colonial government wanted to use this law to put an end to customary land management and to allocate land to those who could actually cultivate it. This law stipulates that rural councils administer the land within the terroir zones. These councils are elected by the population of a rural community, a jurisdiction comprising several villages. The councils do not grant a permanent property right, but rather a right of use for an unlimited period of time based on development and granted to residents of the rural community. These allocations cannot be subject to any form of transaction such as sale, lease or pledge. The sub-prefect, as the representative of the State, must approve the allocations and deallocations by the rural council.

With the adoption of Law No.o 2013-10 of 28 December 2013 (known as Act III of Decentralisation), all rural communities have been transformed into communes. Several land reform efforts have also been carried out since the 1990s, with the last attempt in 2012. To this end, a National Commission on Land Reform was created to propose amendments to the body of legislation. However, President Macky Sall dissolved the National Land Reform Commission in 2017 without implementing its recommendations.

Although land reform remains incomplete, the government nevertheless seems to want to better supervise, and even recentralise, land management. In 2020, the government issued a decree requiring that any allocation of more than 10 hectares be approved by a government representative at the departmental or regional level10. In addition, the Senegalese government launched the Land Registry and Security Project (PROCASEF) in 2021 with funding from the World Bank. PROCASEF aims to register existing land rights to ensure effective land management11.

The mining sector, for its part, is framed by the Mining Policy Declaration adopted on 06 May 2003 and Law n°2016-32 of 08 November 2016 on the Mining Code and its implementing decree n°2017-459 of 20 March 2017. As the mining subsoil belongs to the State, the latter is responsible for granting exploration and mining permits.

Land tenure system

Land in Senegal is divided into three main domains: (1) the national domain, (2) the state domain, and (3) the private domain, which are themselves composed of subcategories. The national domain, which covers most of the country, belongs to the nation as a whole. Within the national domain, the terroir areas include all lands that have not been registered in the private or State domain six months after the promulgation of the 1964 Act.

The State domain includes the movable and immovable property of the State. It is divided into two categories: public and private. The public domain of the State cannot be privately appropriated and is reserved for public purposes. However, the State may sell land or buildings in its private domain. It may also grant long leases for up to 50 years with the possibility of renewal.

Private property includes land owned by natural or legal persons, mainly in urban areas. Private property is registered in the Land Register.

| Categories of land | Subcategories | Owner/Manager | Main legal texts | |

| National domain | Classified areas

| Directorate of Water, Forests, Hunting and Soil Conservation National Parks Branch

| - Law No. 2018-25 of 12 November 2018 on the Forestry Code | |

| Urban areas | City Councils | - Law No.o 64-46 of 17 June 1964 on the National Domain - Law No. 2008-43 of 20 August 2008 on the Town Planning Code - Law No. 2013-10 of 28 December 2013 on the General Code of Local Authorities

| ||

| Terroir areas | Rural Councils (now Municipal Councils) | - Law No.o 64-46 of 17 June 1964 on the National Estate - Law No.o 72-25 of 19 April 1972 on rural communities - Law No. 2013-10 of 28 December 2013 on the General Code of Local Authorities - Decree No. 2020-1773 amending Decree No. 72-1288 of 27 October 1972 - Law n°2021-38 of December 03, 2021

| ||

| Frontier areas (gradually being phased out) | Société d'aménagement et d'exploitation des terres du delta du fleuve Sénégal (SAED) | - Law No.o 64-46 of 17 June 1964 on the National Estate | ||

| State domain | Private domain | Directorate General of Taxes and Estates | - Law No. 76-66 of 2 July 1976 on the State Property Code | |

| Public domain | Natural domain | |||

| Artificial domain | ||||

| Private domain of individuals | Individuals holding title to land | - Law No. 2011-07 of 30 March 2011 on land ownership | ||

| Source: adapted from Gagné, Marie. 2020. The Politics of Large-Scale Land Acquisitions: State Support, Community Responses, and Variations in Corporate Land Control in Senegal. D. thesis, Department of Political Science, University of Toronto, Canada. | ||||

Under these categories, land can be obtained through three main mechanisms: (1) an "allocation" granted by a municipal council that confers use rights on land belonging to the terroir area; (2) long leases authorised by the central government for land located on the state's private domain; and (3) title deeds under the private domain12.

Land use trends

In Senegal, pressure on land is fuelled by population growth. Senegal's population has more than tripled in four decades, from 4.96 million in 1976 to 17.21 million in 2021. Cities are absorbing much of this population growth. Thus, the urbanisation rate has increased from 34% in 1976 to 47.38% in 2021. Nevertheless, the majority of the population remains rural, with 52.62% living in the countryside.

At the national level, the population density was 65 inhabitants per km² in 2013, reaching 88 inhabitants per km² in 2021. However, the density varies greatly by region. The population is concentrated in the western and central parts of the country. In particular, the Dakar region recorded a density of 5 739 inhabitants per km² in 2013, reaching a peak of 25 385 inhabitants per km2 in the department of Guédiawaye. The East and North are comparatively sparsely populated. With 9 inhabitants per km2 , the Kédougou region has the lowest density in the country13.

Forest area is declining in Senegal, although the rate of decline has slowed in recent years. Between 1990 and 2000, it is estimated that 45 000 hectares of forest disappeared per year.From 2000 to 2010, the annual rate of forest area loss decreased to 38,500 hectares, and between 2010 and the present, the net annual loss has increased to 40,000 hectares. In 30 years, Senegal's forests have lost 1,235,000 hectares, from 9,303,160 hectares in 1990 to 8,068,160 hectares in 2020. If we relate these figures to the total surface area of the country, this means that forests currently cover approximately 41% of Senegal's territory. However, many of these forests are severely degraded.

Among the causes of deforestation are the supply of woody fuels to households for charcoal making, bush fires, land clearing and slash-and-burn for agriculture, as well as illegal wood trafficking in the south of the country. The Senegalese government has promised to create nine new classified forests in 2021, with a total area of 84,726 hectares. Before this announcement, classified forests in Senegal covered 1,385,110 hectares14.

Baobab and palm forest in Senegal, photography by ManuB (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Arab lands cover 7,899,090 hectares in Senegal. In 2010, cultivated land represented a total of 4,713,878 hectares, i.e. 24% of Senegalese territory15. The fertility of Senegal's land has declined sharply due to water and wind erosion, the use of chemical fertilisers, reduction in vegetation cover, deforestation, overgrazing, neglect of fallow land, erratic rainfall, as well as soil salinisation and acidification. It is estimated that in 2010, 63% of arable land in Senegal was severely degraded. According to another study, only 15% of the land is suitable or moderately suitable for agriculture, while the remaining 85% varies from moderately poor to unsuitable16.

In addition, rising ocean water levels are likely to increase saltwater intrusion and thus worsen soil salinity problems in coastal areas. Under different scenarios by 2100, coastal erosion could result in the loss of 11-157 km2 of land, while flooding could engulf up to 2149 km2 of land17.

Boy preparing land in Senegal, photo by IFPRI/Milo Mitchell (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Investments and land acquisitions

Land acquisitions by domestic and foreign investors have increased significantly in Senegal since the 2000s. The practice of selling and lending land, in principle illegal, has intensified throughout the country, especially "in areas of high agricultural potential" such as the Niayes or the Senegal River valley18.

These large-scale land acquisitions peaked in 2008 and then declined from 2012. It is not uncommon for local people to oppose the arrival of investors from outside their community, contributing to the stopping of contested projects. In addition, after a boom, the government-promoted biofuel sector has virtually collapsed. As of 2020, many biofuel projects covering over 524,030 hectares have been abandoned19.

The mining industry is also growing in Senegal. Long dominated by phosphate mining, the sector has seen the opening of gold mines in the southeast of the country in recent years. Three gold companies are currently operating in the Kédougou region and other mining projects are in the pipeline. Zircon mining on the coastline between Dakar and Saint-Louis is also under development. In 2007, Australia's Mineral Deposits Limited (Mdl) obtained a 25-year licence to establish the world's third largest zircon and ilmenite mine. 50,000 people are reportedly affected by the company's activities, of whom 1,500 have been displaced so far. The forthcoming expansion of the mine raises concerns about the sustainability of market gardening and tourism activities in the area20. Like agricultural projects, mining concessions are often blocked or delayed because of opposition from the populations concerned. Overall, only 35% of the agricultural and mining projects announced since 2000 in Senegal are operational, the rest being completed, suspended or uncertain21.

In addition, the government of Abdoulaye Wade allowed the installation of several hotel complexes along the coast on land belonging to the public maritime domain22. The development of infrastructures by the Senegalese State under Abdoulaye Wade and Macky Sall (such as Blaise-Diagne International Airport, the mineral port of Bargny, various urban centres, the Dakar Regional Express Train) has also led to several displacements of populations and declassification of forests.

Community land rights

An increasing number of individuals are seeking to formalise their land ownership through an allotment granted by municipal councils (formerly called rural councils), mainly in agro-industrial areas. However, the majority of people in rural areas continue to own their land under customary law. As of 2015, only 152,000 land titles had been issued, out of a population of 13 million23.

Under customary law, access to land is largely determined by social rank, gender, marital status and age in Senegal. Descendants of the first group historically settled in a given area are the owners of the land, who transmit their land heritage within the lineage. Customary land allocation tends to perpetuate social inequalities, as the descendants of the former landowners

continue to control the majority of land. For example, in the Senegal River valley, men from the noble caste rent out part of their land holdings to individuals from lower castes in a form of sharecropping. Unmarried men, on the other hand, have no managerial power over the land of the lineage and only obtain a plot once they are married24.

Women's land rights

The National Estate Act promulgated in 1964 is essentially aimed at promoting access to land by those who can cultivate it. Although the law does not mention women, it does in principle allow women to obtain land allocations as long as they maintain their capacity to develop their plots.

More recent laws and measures contain explicit provisions for greater gender equality in land tenure. For example, Article 15 of the 2001 Constitution clearly states that "Men and women shall have equal access to the possession and ownership of land under the conditions determined by law"25.

For its part, the 2004 Agro-Sylvo-Pastoral Orientation Law, through its Article 54, charges the State with ensuring "parity of rights between men and women in rural areas, in particular farming" and granting women "facilities to access land and credit"26. In 2016, Senegal also joined the campaign of the African Union (AU) Commission, the UN Economic Commission for Africa and the African Development Bank to allocate 30% of documented land to African women to improve their land rights27.

Despite these legislative and political advances, only 15% of plots are exploited by women in Senegal28. The State itself is struggling to achieve its own objectives. Thus, the Société d'Aménagement et d'Exploitation des Terres du Delta du Fleuve Sénégal (SAED), the state agency in charge of developing irrigated areas, aims to allocate only 15% of new agricultural developments to women29.

Women's lack of awareness of their land rights, the persistence of traditional identity norms and discriminatory socio-cultural dynamics are among the factors limiting women's access to land in Senegal. In addition, the municipal councils responsible for allocating land remain dominated by male notables who have an interest in maintaining the status quo or defying the authority of customary chiefs in land management.

The patrilineal mode of descent amplifies men's resistance to allocating land permanently to women, as they fear the fragmentation of land assets outside the lineage. Women's access to land is mainly precarious through their husbands. In most societies in Senegal, women cannot inherit land, either from their family of origin or from their family by marriage. When the husband dies, the land reverts to the family or sons of the deceased. In the event of divorce, the man keeps the land without paying compensation to his wife for her years of contribution to the farm work.

Women have little better access through allocation by municipal councils. Because women generally obtain land through groups, the areas they cultivate amount to a few square metres per capita. Often these are plots of land that are not used by men because of their low fertility or their distance from water sources. In order to farm individually, women usually have to rent the land at a high price and hire farm labourers, thus limiting their profit margin30.

Urban Land Tenure

Law No. 66-49 of 27 May 1966 on the town planning code, revised in 1988 and 2008, is the main document regulating urban development. However, the development of cities takes place largely outside the legal framework.

Located on the Cape Verde peninsula, the city of Dakar has experienced a marked demographic increase since the 1970s, fuelled by rural emigration and a high natural growth rate. The population has risen from 400,000 in 1970 to 3.9 million in 2021. Although its surface area represents only 0.3% of the national territory, the administrative region of Dakar was home to nearly a quarter of the total population (23.2%) in 2013. With the horn of Cape Verde saturated, the city is experiencing a strong urban sprawl to the east, encroaching on former rural land.

Land scarcity also stimulates real estate speculation. The high cost of rents and the lack of housing lead to overcrowding and the expansion of informal settlements. Thus, it is estimated that 35 to 40% of the urbanised area of the Dakar region is made up of irregular neighbourhoods poorly provided with services and infrastructure31.

Aerial view of Dakar, photography by Gabriel de Castelaze (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Since the 1980s, some regional cities and the outlying districts of Dakar have experienced periodic flooding during the rainy season. In Dakar, these floods occur in a context of occupation of wet marshy areas (the Niayes), poorly controlled urban development and the absence of a rainwater drainage system. These floods alter the urban landscape: they destroy buildings, infrastructures such as roads and bridges, as well as peri-urban agricultural areas. Entire neighbourhoods have been abandoned to water and vegetation that has become overgrown. In 2006, the government started the construction of subsidised housing to relocate people from flooded neighbourhoods to the greater periphery. Since 2010, concerted actions and the installation of underground canals draining rainwater to the sea have reduced the flooded areas in the suburbs. However, there are still pockets of flooding in some municipalities32.

In order to relieve congestion in the capital, the government has been building various urban centres, such as Daga Kholpa and Diamniadio, for several years. The State has thus secured a land base of 13,000 hectares which it intends to develop for the creation of 27 urban centres. Of these 13,000 hectares, 10,800 are located in the Dakar-Thiès-Mbour axis alone33. However, the construction of new housing in peri-urban areas often competes with market gardening areas.

Land innovations

Coastal Senegal has a particular ecosystem: that of the mangroves. These are mangrove forests that grow in the Casamance River, in the Saloum estuary and at the mouth of the Senegal River. Senegal's former environment minister, Haïdar El Ali, launched a vast mangrove reforestation programme in 2009 to combat rising water levels and soil salinisation in Casamance. Since then, 152 million trees have been planted, enabling the recovery of 10 000 hectares of mangroves34.

Mangrove in the Saloum delta, photography by tjabeljan (CC BY 2.0)

Timeline - milestones in land governance

1964: With the adoption of Law 64-46 of 17 June 1964 on the National Domain, the Senegalese government aims to abolish customary land rights.

1972: Law 72-25 of 19 April 1972 marks the advent of rural communities, which are responsible for managing land in local areas. A total of 320 rural communities are gradually created.

1996: With Law No. 96-06 of 22 March 1996 on the Local Authorities Code, the government continued its decentralisation process and transferred various powers to the regional councils, including forest clearing authorizations.

2013 : Senegal initiates a new reform called "Act III of Decentralisation" whose objective is to organise Senegal "into viable, competitive territories that bring sustainable development." The government abolishes the regional councils in the process.

2012: The government launches a reform process to modernise the architecture of land laws. However, the reform remains incomplete.

2020 : The government enacts legislation to regulate land allocations by municipal councils.

Where to go next?

The author's suggestions for further reading

I recommend the series Terres de feu produced by the Maison des Reporters in 2020. The various reports and interviews offer a panorama of the various issues of land governance in Senegal (peri-urban agriculture, women's rights, land reform, mining, etc.).

For a portrait of urban land transformations due to industrialization, I suggest an interactive website dedicated to the municipality of Bargny, which discusses the difficulties encountered by the area's residents, from the installation of a cement factory in 1948, to the construction of a coal-fired power plant, the development of an urban pole and the announcement of the arrival of an ore port. Located in the suburbs of Dakar, this township inhabited by fishermen is also suffering from coastal erosion. The site contains several photos, videos, maps and testimonies that reflect the reality experienced by the local populations.

For an assessment about the state of land information in Tanzania - how open and accessible land information is - please check the SOLI report for this country published by the Land Portal.

References

[1] World Bank. 2021. « Country profile : Senegal », World Development Indicators. URL:https://data.worldbank.org/country/senegal.

[2] Agence nationale de la statistique et de la démographie. 2014. Rapport définitif. RGPHAE 2013. Dakar : République du Sénégal. URL : https://www.ansd.sn/ressources/rapports/Rapport-definitif-RGPHAE2013.pdf. Centre de suivi écologique. 2020. Rapport sur l’état de l’environnement au Sénégal. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/rapport-sur-l%C3%A9tat-de-lenvironnement-au-s%C3%A9n%C3%A9gal.

[3] Agence nationale de l'Aménagement du Territoire. 2020. Plan national d’aménagement et de développement territorial (PNADT): Horizon 2035. Dakar: République du Sénégal. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/plan-national-d%E2%80%99am%C3%A9nagement-et-de-d%C3%A9veloppement-territorial-pnadt

[4] Niang, Aminata, Ndèye Fatou Mbenda Sarr, Ibrahima Hathie, Ndèye Coumba Diouf, Cheikh Oumar Ba, Ibrahima Ka, and Marie Gagné. 2017. Understanding changing land access and use by the rural poor in Senegal. London: IIED. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/understanding-changing-land-access-and-use-rural-poor-senegal.

[5] Agence nationale de l'Aménagement du Territoire. 2020. Plan national d’aménagement et de développement territorial (PNADT): Horizon 2035. Dakar: République du Sénégal. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/plan-national-d%E2%80%99am%C3%A9nagement-et-de-d%C3%A9veloppement-territorial-pnadt. Tappan, G.G., M.Sall, E.C. Wood, and M.Cushing. 2004. « Ecoregions and land cover trends in Senegal ». Journal of Arid Environments no. 59:427-462. https://www.environnement.gouv.sn/informations-sur-l-environnement/environnement-et-ressources-naturelles

[6] Cruise O'Brien, Donal B. 1975. Saints & politicians: Essays in the organisation of a Senegalese peasant society. London: Cambridge University Press.

[7]Delgado, Christopher L., and Sidi Jammeh. 1991. « Introduction: Structural change in an hostile environment ». The political economy of Senegal under structural adjustment, Christopher L. Delgado et Sidi Jammeh (dir.). New York: Praeger Publishers, 1-20.

[8]Le jatropha curcas est une plante non comestible dont les grains peuvent être transformés en huile utilisée dans la fabrication du biocarburant.

[9] République du Sénégal. Non daté. Plan Sénégal Émergent. URL : https://www.un-page.org/files/public/plan_senegal_emergent.pdf.

[10] République du Sénégal, Décret n° 2020-1773 modifiant le décret n° 72-1288 du 27 octobre 1972 relatif aux conditions d’affectation et de désaffectation des terres du domaine national. URL :https://landportal.org/library/resources/d%C3%A9cret-n%C2%B0-2020-1773-modifiant-le-d%C3%A9cret-n%C2%B0-72-1288-du-27-octobre-1972-relatif-aux

[11]http://www.finances.gouv.sn/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/PROCASEF-Cadre-de-Gestion-Environementale-et-Sociale.pdfé

[12] Dieye, Abdoulaye. 2020. « La question foncière au Sénégal : une équation... ». Gouvernance foncière au Sénégal: Terres de feu. Dakar: La Maison des Reporters. URL :Gagné, Marie. 2020. The Politics of Large-Scale Land Acquisitions: State Support, Community Responses, and Variations in Corporate Land Control in Senegal. Thèse de doctorat, Département de science politique, University of Toronto, Canada

[13] Agence nationale de l'Aménagement du Territoire. 2020. Plan national d’aménagement et de développement territorial (PNADT): Horizon 2035. Dakar: République du Sénégal. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/plan-national-d%E2%80%99am%C3%A9nagement-et-de-d%C3%A9veloppement-territorial-pnadt

Agence nationale de la statistique et de la démographie. 2014. Rapport définitif. RGPHAE 2013. Dakar : République du Sénégal. URL : https://www.ansd.sn/ressources/rapports/Rapport-definitif-RGPHAE2013.pdf.

ANSD. « Le Sénégal en bref ». URL : https://satisfaction.ansd.sn. Voir aussi https://satisfaction.ansd.sn/ressources/publications/indicateurs/Projections-demographiques-2013-2025.htm.

[14] Badji, Mamadou, and Olimata Faye. 2020. Évaluation des ressources forestières mondiales. Rapport Sénégal. Rome: FAO. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/e%CC%81valuation-des-ressources-forestie%CC%80res-mondiales-rapport-s%C3%A9n%C3%A9gal.

Le Quotidien. 2021. « Protection de l’environnement : 9 nouvelles forêts classées dans 4 régions ». 2 mars. URL : https://landportal.org/news/2022/01/protection-de-l%E2%80%99environnement-9-nouvelles-for%C3%AAts-class%C3%A9es-dans-4-r%C3%A9gions.

[15] Agence nationale de l'Aménagement du Territoire (ANAT). 2020. Plan national d’aménagement et de développement territorial (PNADT): Horizon 2035. Dakar: Ministère des Collectivités territoriales du Développement et de l’Aménagement des Territoires; République du Sénégal. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/plan-national-d%E2%80%99am%C3%A9nagement-et-de-d%C3%A9veloppement-territorial-pnadt.

Centre de suivi écologique. 2020. Rapport sur l’état de l’environnement au Sénégal. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/rapport-sur-l%C3%A9tat-de-lenvironnement-au-s%C3%A9n%C3%A9gal.

[16] Centre de suivi écologique. 2020. Rapport sur l’état de l’environnement au Sénégal. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/rapport-sur-l%C3%A9tat-de-lenvironnement-au-s%C3%A9n%C3%A9gal.

Ndiaye, Mansour. 2015. « La dégradation des terres au Sénégal : la réponse à partir des Arbres Fertilitaires ». Agridape no. 31 (1):14-15. URL : https://www.iedafrique.org/IMG/pdf/AGRIDAPE_31-1_Des_Sols_durables.pdf.

[17] République du Sénégal. 2009. Rapport national sur le développement humain au Sénégal. Changement climatique, sécurité alimentaire et développement humain. URL: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/rndh_senegal_2010.pdf

[18] Delville, Philippe Lavigne, Jean-Philippe Colin, Ibrahima Ka, and Michel Merlet. 2017. Étude régionale sur les marchés fonciers ruraux en Afrique de l’Ouest et les outils de leur régulation. UEMOA/IPAR.

Touré, Oussouby, Cheikh Oumar Ba, Abdoulaye Dieye, Mame Ounéta Fall, and Sidy Mohamed Seck. 2013. Cadre d’Analyse de la Gouvernance Foncière au Sénégal (CAGF). Dakar: Initiative Prospective Agricole et Rurale (IPAR). URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/cadre-d%E2%80%99analyse-de-la-gouvernance-fonci%C3%A8re-au-s%C3%A9n%C3%A9gal-french.

[19] Gagné, Marie, and Ashley Fent. 2021. « The faltering land rush and the limits to extractive capitalism in Senegal ». The Transnational Land Rush in Africa: A Decade After the Spike, Logan Cochrane et Nathan Andrews (dir.), 55-85. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/faltering-land-rush-and-limits-extractive-capitalism-senegal.

[20] Idrac, Charlotte. 2021. « Sénégal: exploitation du zircon, quel impact social et environnemental ». RFI, 7 novembre. URL: https://www.rfi.fr/fr/podcasts/reportage-afrique/20210710-sénégal-exploitation-du-zircon-quel-impact-social-et-environnemental.

Pauron, Michael. 2012. « Sénégal - Mines, naissance d'un géant, au nord de Diogo ». Jeune Afrique, 22 mars. URL: http://www.jeuneafrique.com/Article/JA2670p058-059.xml0/.

Sidy, Abdoulaye. 2013. « Exploitation de zircon a Diogo - Les populations au régime sec ». Walfadjri, 31 juillet. URL: http://fr.allafrica.com/stories/201308010043.html.

[21] Gagné, Marie, and Ashley Fent. 2021. « The faltering land rush and the limits to extractive capitalism in Senegal ». The Transnational Land Rush in Africa: A Decade After the Spike, Logan Cochrane et Nathan Andrews (dir.), 55-85. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/faltering-land-rush-and-limits-extractive-capitalism-senegal.

[22] Laplace, Manon, et Marième Soumaré. 2020. « Sénégal : Dakar, presqu’île en danger. » Jeune Afrique, 14 juillet. URL : https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1009473/politique/senegal-dakar-presquile-en-danger/.

[23] Agence de presse sénégalaise. 2015. « 95% des terres échappent aux Sénégalais (Moustapha Sourang) ». 29 mai. URL: http://www.aps.sn/articles.php?id_article=142754.

[24] Parent-Chartier, Clothilde. 2020. « Quels sont les facteurs de résistance à l’égalité des genres? Le cas de l’accès des femmes à la terre dans la région du Fuuta ». Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue canadienne d'études du développement no. 41 (4):544-560. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/quels-sont-les-facteurs-de-re%CC%81sistance-a%CC%80-l%E2%80%99e%CC%81galite%CC%81-des-genres

[25]République du Sénégal, Loi n° 2001-03 du 22 janvier 2001 portant Constitution, JORS, numéro spécial 5963 du 22 janvier 2001, p. 27. URL: https://www.sec.gouv.sn/lois-et-reglements/constitution-du-sénégal.

[26] République du Sénégal, Loi n° 2004-16 du 4 juin 2004 portant loi d’orientation agro-sylvo-pastorale. J.O. N° 6176 du SAMEDI 14 AOUT 2004. URL: http://www.jo.gouv.sn/spip.php?article5381.

[27] Diallo, Seydina Bilal. 2020. « Foncier agricole au Sénégal: Quand le machisme pollue la terre! ». Gouvernance foncière au Sénégal: Terres de feu. Dakar: La Maison des Reporters. URL: https://landportal.org/node/98198.

[28] Direction de l'Analyse, de la Prévision et des Statistiques Agricoles. 2020. Rapport de la phase 1 de l’Enquête Agricole Annuelle (EAA) 2019-2020. URL : https://dapsa.gouv.sn/sites/default/files/publications/Rapport_final_EAA_2018_2019_5.pdf

[29] Dakaractu. 2021. « Accès des femmes au foncier : L’engagement des ministères en charge de la femme et de l’agriculture ». 18 décembre. URL: https://landportal.org/news/2022/01/acc%C3%A8s-des-femmes-au-foncier-l%E2%80%99engagement-des-minist%C3%A8res-en-charge-de-la-femme-et-de-l

[30] Diallo, Seydina Bilal. 2020. « Foncier agricole au Sénégal: Quand le machisme pollue la terre! ». Gouvernance foncière au Sénégal: Terres de feu. Dakar: La Maison des Reporters. URL: https://landportal.org/node/98198.

Enda Pronat. 2011. Amélioration et sécurisation de l’accès des femmes au foncier au Sénégal. Dakar. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/am%C3%A9lioration-et-s%C3%A9curisation-de-l%E2%80%99acc%C3%A8s-des-femmes-au-foncier-au-s%C3%A9n%C3%A9gal.

Parent-Chartier, Clothilde. 2020. « Quels sont les facteurs de résistance à l’égalité des genres? Le cas de l’accès des femmes à la terre dans la région du Fuuta ». Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue canadienne d'études du développement no. 41 (4):544-560. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/quels-sont-les-facteurs-de-re%CC%81sistance-a%CC%80-l%E2%80%99e%CC%81galite%CC%81-des-genres.

[31] ANSD. 2014. Rapport définitif. RGPHAE 2013. Dakar: Agence nationale de la statistique et de la démographie, Ministère de l’Economie, des Finances et du Plan, République du Sénégal. URL: https://www.ansd.sn/ressources/rapports/Rapport-definitif-RGPHAE2013.pdf.

ANSD. « Le Sénégal en bref ». URL: https://satisfaction.ansd.sn.

Mane, Mansour. 2021. « Les pôles urbains du triangle Dakar – Thiès – Mbour et la politique du logement social ». ACRESA. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/les-po%CC%82les-urbains-du-triangle-dakar-%E2%80%93-thies-%E2%80%93-mbour-et-la-politique-du-logement.

[32] GFDRR. 2014. Sénégal: Inondations urbaines. URL: https://www.gfdrr.org/sites/default/files/publication/rfcs-2014-senegal-fr.pdf

Leclercq, Romain. 2019. « L’action publique à l’épreuve des inondations dans la banlieue de Dakar ». Anthropologie & développement no. 50:31-50. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/l%E2%80%99action-publique-%C3%A0-l%E2%80%99%C3%A9preuve-des-inondations-dans-la-banlieue-de-dakar

[33] https://www.urbanisme.gouv.sn/realisations/100-000-logements

[34] Delpierre, Antoine. 2019. « Au Sénégal, 152 millions d'arbres plantés dans la mangrove du delta de Casamance ». TV5 Monde, 24 octobre. URL : https://information.tv5monde.com/video/au-senegal-152-millions-d-arbres-plantes-dans-la-mangrove-du-delta-de-casamance.https://information.tv5monde.com/video/au-senegal-152-millions-d-arbres-plantes-dans-la-mangrove-du-delta-de-casamance.

Authored on

24 August 2022