By Daniel Hayward, reviewed by Dr. Joanna Millar, Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University, Australia

16 September 2021

Bhutan is a small landlocked country sandwiched between the two economic powerhouses of India and China. It covers 38,394km2, which is slightly smaller than Switzerland. In 2020, the population stood at 771,612, and even though this figure has tripled since 1960, it is still less than 10% the population of present-day Switzerland1. Geographically, the country comprises foothills and high mountainous terrain in the eastern Himalayas2. Administratively, it is split into twenty dzongkhag (districts).

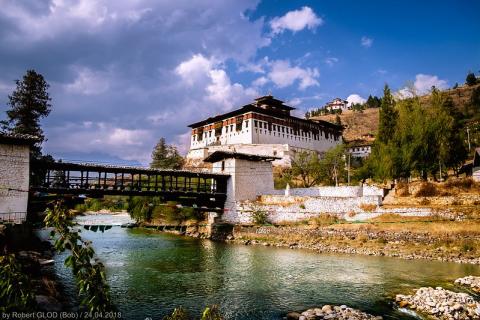

Land is often registered in the names of women, however, decisions about land may remain with male members of the household

Photo: Robert Glod/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

A hereditary monarchy has ruled Bhutan since 19073. In 1998 direct royal rule ceased under the 4th King, replaced by an appointed cabinet of ministers. In 2008, a new constitution was enacted stipulating the transition to an elected parliamentary democracy4. Three elections have been held since this shift, most recently in 2018 where the People-Centered and Pragmatic Party (DNT - Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa) gained power5. The state is officially secular, although Buddhism has a key role throughout society and culture. The present monarch is Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, the 5th King of Bhutan.

Paro Taktsang Buddhist monastery, CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication

Bhutan is seen as a development success story. There was a significant drop in poverty since the millennium, decreasing by more than 60% (according to the national poverty rate) in the ten years up to 20196. The country is still classed as an LDC (Least-Developed Country) but is hoping to graduate upwards in 2023. Bhutan measures development in both economic and non-economic terms, through the index of Gross National Happiness (GNH). The index was first conceptualised in 1972, operating around four key pillars of sustainable socio-economic development, environmental conservation, the preservation and promotion of culture, and good governance. Economic development in Bhutan carries strong potential through abundant access to natural resources and human capital. Between 1981 and 2017 GDP grew by an average of 7.5% per annum, placing Bhutan as one of the top five fastest growing economies in the world. A major influence on these figures is hydropower generation7.

Another significant factor is high-end tourism, which generates both revenue and employment opportunities, and focuses on nature- and culture-based experiences8. With thousands of Bhutanese workers working and studying abroad, there is also an important inflow of remittances to the country. Agriculture remains vital to the livelihoods of a predominantly rural population, even if the harsh topography of the country limits the availability of arable land9.

Land legislation and regulations

The modern legal system of Bhutan is quite young, with the country only becoming organised as a centralised state during the reign of the 3rd King (1952-72)10. The 2008 Constitution signals the shift to an elected democracy and allows all citizens the right to own property, including land.

The principal legislation for land is the Land Act. The most recent 2007 Land Act defines the categories that may be kept as thram or private land (see next section on land tenure). Stipulations are provided on how to register land, the rights and obligations of landowners, and regulations on transfer and sale. A land ceiling is given at 25 acres per family (with certain exemptions such as for members of the royal family, government institutions, and community groups owning land for social and religious purposes). The National Land Commission acts to administer the law, bringing all registered land under cadastral survey.

There are also definitions in the Land Act on state-owned land, which is split into government land (in urban areas) and government reserved forest land (rural). There is an express aim in the law to counter historical inequalities in land access and ownership, by redistributing grazing leases through the nationalisation of grazing land (tsamdro)11. This process was first stipulated in the 1979 Land Act, and the 2007 version confirms that tsamdro and sokshing (managed forest areas for leaf litter) are no longer forms of thram, with a government aim to buy back rights from titleholders and convert these areas to reserved forest land12.

Following the process of nationalisation, a leasing program was planned for 2017/ 2018, although some leaseholds were already submitted in 2015. The aim is to end inter-district pastoralism and improve sustainable and economically productive use of land. However, progress in providing leaseholds has been slow, further delayed by the onset of COVID-19. The governance of leaseholds is supported through 2018 Land Lease Rules and Regulations. The Rules encourage farmers to sub-lease their own land to consolidate and improve productivity13.

Forestlands were nationalised through the Forest Act of 196914. The first National Forest Policy was introduced in 1974, with a further update in 2011. The main legislation governing forests in the present day is the Forest and Nature Conservation Act of 1995, which has been supplemented through Forest and Nature Conservation Rules in 2006 and then 201715.

Land tenure classifications

There are two basic forms of land tenure in Bhutan, namely freehold and leasehold. Traditionally, private land (thram) was owned through a system of deeds by which taxes were paid to the king16. The two main areas of agricultural thram are chhuzhing (areas of wetland cultivation) and kamzhing (areas if dryland cultivation). Both these are present as traditional categories and in the 2007 Land Act. Further categories of private land (thram) in the Land Act include:

- Areas for cash crop production

- Residential land

- Industrial land

- Commercial land

- Recreational land

- Institutional land

As designated in the 1979 and 2007 Land Acts, two private (or communal) land categories have been nationalised:

- sokshing (a managed tree area for leaf litter)

- tsamdo (pasturelands)

Traditionally, little distinction is made between pastureland, rangeland and forest, particularly since grazing often takes place in forest areas17. Tsamdro were traditionally governed under customary rights, but many areas are now located in protected areas of Bhutan18. In the transition to nationalise tsamdro and sokshing, with the intention to lease back to herders, an unclear communication of legal changes has created confusion and concern in the herder community19.

Yak grazing on dwarf bamboo, entrance of Phobjikha valley, Bhutan, photo by L. Shyamal, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.5) license

There is an issue of land scarcity in Bhutan, with a lack of arable land, and increasing fragmentation of existing holdings20. One means to address this situation has been through the kidu land programme. Dating from the 17th century, kidu is a form of social security where the king provides relief for the poor and vulnerable (for example in money, land, or citizenship). It was given emphasis by the king in the 1950s as part of a series of reforms, including the provision of land to the landless21. From 2009-13, the programme had 61,339 beneficiaries22.

According to national surveys, the security of property rights is not deemed to be the base for serious conflict in Bhutan23. Yet there are examples of local conflict over land-use and other resources, for example between yak herders and downstream communities where property rights remain unclear24. Another issue of contention involves the Lhotshampa. These are people of Nepalese origin, who make up around one sixth of the national population but are not permitted Bhutanese citizenship and so are unable to exercise property rights. Since the late-1980s, there have been periods of mass expulsion of Lhotshampa groups from the country, and there remain 18,000 refugees in camps in Nepal, hoping to return to Bhutan25.

Land use trends

Due to the mountainous terrain, there is a limited area suitable for agriculture, with less than 2% of total land deemed arable26. Farming is predominantly limited to river valleys and are generally small parcels on sloping land. Via government statistics from 2015, the average land holding is 1.4 ha27. There is also a considerable amount of pastoralism in Bhutan, led by yak herding28.

Despite the small land area used for crop production, subsistence farming remains a key economic activity, in 2019 employing 56% of the national workforce but contributing only 16% of GDP29. Land scarcity is further exacerbated by rural to urban migration, resulting in a feminisation of the agricultural sector, lack of mechanisation and irrigation, and land conversion for urban development30. This threatens national food security, with 30% of food imported from India31. In 2020, 42.3% of the population were residing in municipal areas32. The capital Thimpu grew from 30,000 residents in 1993 to 138,736 in 2017 which is 19.1% of the national population33.

View of Thimphu city, photo by Gerd Eichmann, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license

Forest covers 72% of Bhutan, and the constitution sets a minimum coverage of 60% national land34. Almost all forest areas are under public governance, with less than 1% being private forest. 51% of public forest is designated protected status. There are five national parks, four wildlife sanctuaries, one strict nature reserve, and nine interconnecting biological corridors35. The rest is ‘government reserve forest’ sub-divided in categories such as forest management unit, local forest, and community forest. Nevertheless, although there is some illegal logging, there is yet to be a significant exploitation of forests, with only 6% of forest areas under commercial management. By 2018, there were 718 community forests, benefitting a third of the population36.

Bhutan has abundant water resources with great potential for hydropower. There is a strong impact of monsoon rains from late June to late September, which contribute to floods and landslides37. There are also risks from earthquakes, glacial lake outbursts and droughts, which could be exacerbated by climate change.

Land investments and acquisitions

Large development projects in Bhutan have centred around hydropower. These have taken place since the 1970s, including the Chukha and Tala projects, and with the support of financing from India38. They have provided a significant contribution to GDP growth in the country. Further mega-hydropower projects are set to go into operation in 2022 and 2024/5, hoping to take advantage of a power export market. For these and other investments, the constitution states that land may be acquired in the public interest and in payment of fair compensation.

Government and State-owned enterprises dominate the employment market in urban areas. An underdeveloped private sector requires further investment, and certainly in urban areas there is a lack of infrastructure and connectivity. The small domestic market and weak economies of scale, together with a status as a landlocked nation vulnerable to natural disasters, affects Bhutan’s ability to attract foreign investment39. FDI has been less than $20 million per year since 2010, which is a lower proportion of GDP compared to other South Asian countries. There is a limited relationship with China despite sharing a border. Instead, there is a dependency on support from India. 85% of exports are to this country via a liberal trade agreement, and the Bhutanese currency (ngultrum) is pegged to the Indian rupee. Via the constitution, foreign ownership of land is not permitted.

There has been slow progress registering land through the National Land Commission, which otherwise could facilitate acquisition for investment projects. There is also a need to implement legal reform for the support of private sector investors.

Women’s land rights

Under national law, men and women share equal rights40. Equal rights for inheritance to male and female children are stipulated through the 1980 Inheritance Act. However, customary practices may determine ground-level reality. This can benefit women, depending on whether they are part of matrilineal (western and central regions) or patrilineal (south and east) systems found in Bhutan41. Nevertheless, in general women enjoy more freedom and equality than many other developing countries. This extends to land ownership, which is often registered in the names of women42. In economic terms there are a couple of qualifications here. Firstly, the land market is small, and women are less likely than men to use their land to access financing for other businesses. Secondly, decision-making concerning land may remain with male members of the household, regardless of where the registration lies. On 17th July 1980, the Bhutanese government signed the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), ratifying it on 31st August 1981.

Women are underrepresented in both secondary education (completed by 6% of women compared to 14% of men) and the workforce (58% of women employed compared to 83% men)43. There are limitations in career choices for women, who are confined to lower-paid sectors such as agriculture or household-based activities. The 2018-19 economic census sees women’s earnings at 75% the level of men44. With men more likely to migrate to urban areas in search for paid work, the agricultural sector employs more women than men.

In the 2018 national elections, two female candidates were nominated to the National Council and seven to the National Assembly45. Although an improvement, parliamentary representation for women remains weak at 8.3%. Participation is sometimes better at other tiers of authority. For example, most community forestry committee positions are taken by women (in 2010 standing at 58%)46. In 2004, the National Commission for Women and Children (NCWC) was established under the Ministry of Health, carrying organisational autonomy from 200847. Important domestic NGOs catering to gender issues include Respect, Educate, Nurture and Empower Women (RENEW); Bhutan Association of Women Entrepreneurs (BAOWE); and Bhutan Network for Empowering Women (BNEW).

Voluntary Guidelines on Responsible Tenure (VGGT)

FAO has not conducted any VGGT-related activities in Bhutan.

Timeline - milestones in land governance

1972 – Conceptualisation of Gross National Happiness (GNH) index

Perhaps Bhutan’s most famous export, GNH operates around the four key pillars of sustainable socio-economic development, environmental conservation, the preservation and promotion of culture, and good governance.

1995 – Promulgation of Forest and Nature Conservation Act

This is the main legislation governing forests in the present day, supplemented through Forest and Nature Conservation Rules in 2006 and then 2017.

2007 – Promulgation of Land Act

The act defines land types, sets a ceiling for private ownership per family, and stipulates on land management.

2008 – Transition to an elected parliamentary democracy.

In the same year a new constitution is promulgated, confirming the movement away from direct royal rule.

2009-2019 – GDP growth at 7.5% per annum

This places Bhutan as one of the top five fastest growing economies in the world, with hydropower generation a major influence on economic production.

2018 – 718 community forests

This benefits a third of the population.

2019 – Agriculture employs 56% of the population

Subsistence farming dominates the sector, contributing only 16% of GDP.

2021 – Forest covers 72% of Bhutan, with over half this area given protected status

There are five national parks, four wildlife sanctuaries, one strict nature reserve, and nine interconnecting biological corridors.

Where to go next?

The author’s suggestion for further reading

Compared to its close neighbour Nepal, Bhutan is under-researched, lacking an extensive analysis of its land system. Of available works, the author suggests Pain and Pema’s interesting view of land tenure through customary and legal systems prior to the 2007 Land Act48. Their paper pays particular attention on the position of women in these systems. For a subsequent view of how the 2007 Land Act affects grazing rights, the reader is recommended to look at Tenzing et al. 201749. Concerning the land environment in Bhutan, there is important reporting on protected areas (Lham et al. 201850) and forest management (Sears et al. 201751). Finally, for a view of development challenges including how to deal with the lack of private sector investment and climate change, please go to the following World Bank report52.

***References

[1] World Bank. (2021). World Bank Open Data. The World Bank: Working for a World Free of Poverty. https://data.worldbank.org

[2] FAO. (2011). Country profile – Bhutan (FAO Aquastat Reports). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://landportal.org/library/resources/country-profile-%E2%80%93-bhutan

[3] Ibid.

[4] Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2020). BTI 2020 Country Report Bhutan. Bertelsmann Stiftung. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bti-2020-country-report-bhutan

[5] World Bank Group. (2020). Bhutan Systematic Country Diagnostic: Taking Bhutan’s Development Success to the Next Level. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-systematic-country-diagnostic

[6] World Bank. (2019). Bhutan Forest Note: Pathways for Sustainable Forest Management and Socio-equitable Economic Development. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-forest-note

[7] World Bank Group. (2020). Bhutan Systematic Country Diagnostic: Taking Bhutan’s Development Success to the Next Level. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-systematic-country-diagnostic

[8] Ghosh, B. K., & Suman, S. (2020). Implications of Paradigm Shift in Tourism Policy: An Evidence of Bhutan. Prabandhan Indian Journal of Management. https://landportal.org/library/resources/09752854/implications-paradigm-shift-tourism-policy-evidence-bhutan

[9] CIAT. (2017). Climate-Smart Agriculture in Bhutan. International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), the World Bank, the UK Government’s Department for International Development (DFID). https://landportal.org/node/86941

[10] Pain, A., & Pema, D. (2004). The matrilineal inheritance of land in Bhutan. Contemporary South Asia, 13(4), 421–435.

[11] Tenzing, K., Millar, J., & Black, R. (2017). Changes in Property Rights and Management of High-Elevation Rangelands in Bhutan: Implications for Sustainable Development of Herder Communities. Mountain Research and Development, 37(3), 353–366.

[12] Namgay, K., Millar, J. E., & Black, R. S. (2017). Dynamics of grazing rights and their impact on mobile cattle herders in Bhutan. The Rangeland Journal, 39(1), 97–104.

[13] World Bank Group. (2020). Bhutan Systematic Country Diagnostic: Taking Bhutan’s Development Success to the Next Level. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-systematic-country-diagnostic

[14] Bruggeman, D., Meyfroidt, P., & Lambin, E. F. (2018). Impact of land-use zoning for forest protection and production on forest cover changes in Bhutan. Applied Geography, 96, 153–165.

Phuntsho, K., Aryal, K. P., & Kotru, R. (2015). Shifting Cultivation in Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Nepal: Weighing Government Policies against Customary Tenure and Institutions ICIMOD Working Paper 2015/7. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD). https://landportal.org/library/resources/isbn-978-92-9115-349-7-printed-978-92-9115-350-3-electronic/shifting-cultivation

[15] Sears, R. R., Phuntsho, S., Dorji, T., Choden, K., Norbu, N., & Baral, H. (2017). Forest ecosystem services and the pillars of Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness (Occasional Paper 178). Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). https://landportal.org/library/resources/handle1056895081/forest-ecosystem-services-and-pillars-bhutan%E2%80%99s-gross-national

World Bank. (2019). Bhutan Forest Note: Pathways for Sustainable Forest Management and Socio-equitable Economic Development. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-forest-note

[16] Pain, A., & Pema, D. (2004). The matrilineal inheritance of land in Bhutan. Contemporary South Asia, 13(4), 421–435.

[17] Namgay, K., Millar, J. E., & Black, R. S. (2017). Dynamics of grazing rights and their impact on mobile cattle herders in Bhutan. The Rangeland Journal, 39(1), 97–104.

[18] Gyeltshen, T., Tshering, N., Tsering, K., & Dorji, S. (2010). Implication of Legislative Reform under The Land Act of Bhutan, 2007: A case study on Nationalization of Tsamdro & Sokshing and its associated socioeconomic and environmental consequences. Watershed Management Division, Department of Forests and Park Services, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests. https://landportal.org/library/resources/implication-legislative-reform-under-land-act-bhutan-2007-case-study

[19] Tenzing, K., Millar, J., & Black, R. (2017). Changes in Property Rights and Management of High-Elevation Rangelands in Bhutan: Implications for Sustainable Development of Herder Communities. Mountain Research and Development, 37(3), 353–366

[20] Bhutan National Statistics Bureau, & World Bank. (2014). Bhutan Poverty Assessment 2014. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/oaiopenknowledgeworldbankorg1098620353/bhutan-poverty-assessment-2014

[21] Ugyel, L. (2018). Inequality in Bhutan: Addressing it Through the Traditional Kidu System. Journal of Bhutan Studies, 39, 1–20.

[22] Bhutan National Statistics Bureau, & World Bank. (2014). Bhutan Poverty Assessment 2014. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/oaiopenknowledgeworldbankorg1098620353/bhutan-poverty-assessment-2014

[23] Ibid.

[24] Tenzing, K., Millar, J., & Black, R. (2017, July 8). Conflict and mediation in high altitude rangeland property rights in Bhutan. International Association for the Study of the Commons Biennial Conference 2017, Utrecht. https://landportal.org/library/resources/conflict-and-mediation-high-altitude-rangeland-property-rights-bhutan

[25] Aryal, P. (2021, July 15). Bhutan’s well-kept secret: The Lhotshampa Exodus and the plight of the 100,000. Strife. https://www.strifeblog.org/2021/07/15/bhutans-well-kept-secret-the-lhotshampa-exodus-and-the-plight-of-the-100000/

Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2020). BTI 2020 Country Report Bhutan. Bertelsmann Stiftung. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bti-2020-country-report-bhutan

[26] FAOSTAT. (2021). FAOSTAT database. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/

[27] Chhogyel, N., & Kumar, L. (2018). Climate change and potential impacts on agriculture in Bhutan: A discussion of pertinent issues. Agriculture & Food Security, 7(1), 79. https://landportal.org/library/resources/climate-change-and-potential-impacts-agriculture-bhutan-discussion-pertinent

[28] Gyeltshen, T., Tshering, N., Tsering, K., & Dorji, S. (2010). Implication of Legislative Reform under The Land Act of Bhutan, 2007: A case study on Nationalization of Tsamdro & Sokshing and its associated socioeconomic and environmental consequences. Watershed Management Division, Department of Forests and Park Services, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests. https://landportal.org/library/resources/implication-legislative-reform-under-land-act-bhutan-2007-case-study

[29] World Bank. (2021). World Bank Open Data. The World Bank: Working for a World Free of Poverty. https://data.worldbank.org/

[30] Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2020). BTI 2020 Country Report Bhutan. Bertelsmann Stiftung. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bti-2020-country-report-bhutan

World Bank Group. (2020). Bhutan Systematic Country Diagnostic: Taking Bhutan’s Development Success to the Next Level. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-systematic-country-diagnostic

[31] Chhogyel, N., & Kumar, L. (2018). Climate change and potential impacts on agriculture in Bhutan: A discussion of pertinent issues. Agriculture & Food Security, 7(1), 79. https://landportal.org/library/resources/climate-change-and-potential-impacts-agriculture-bhutan-discussion-pertinent

CIAT. (2017). Climate-Smart Agriculture in Bhutan. International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), the World Bank, the UK Government’s Department for International Development (DFID). https://landportal.org/node/86941

[32] (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2020)

[33] Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2020). BTI 2020 Country Report Bhutan. Bertelsmann Stiftung. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bti-2020-country-report-bhutan

[34] CIAT. (2017). Climate-Smart Agriculture in Bhutan. International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), the World Bank, the UK Government’s Department for International Development (DFID). https://landportal.org/node/86941

World Bank Group. (2020). Bhutan Systematic Country Diagnostic: Taking Bhutan’s Development Success to the Next Level. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-systematic-country-diagnostic

[35] Lham, D., Wangchuk, S., Stolton, S., & Dudley, N. (2019). Assessing the effectiveness of a protected area network: A case study of Bhutan. Oryx, 53(1), 63–70. https://landportal.org/library/resources/assessing-effectiveness-protected-area-network-case-study-bhutan

[36] World Bank. (2019). Bhutan Forest Note: Pathways for Sustainable Forest Management and Socio-equitable Economic Development. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-forest-note

[37] FAO. (2011). Country profile – Bhutan (FAO Aquastat Reports). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://landportal.org/library/resources/country-profile-%E2%80%93-bhutan

[38] World Bank Group. (2020). Bhutan Systematic Country Diagnostic: Taking Bhutan’s Development Success to the Next Level. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-systematic-country-diagnostic

[39] Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2020). BTI 2020 Country Report Bhutan. Bertelsmann Stiftung. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bti-2020-country-report-bhutan

[40] JICA. (2017). Survey of Country Gender Profile (Kingdom of Bhutan). Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), IC Net Limited. https://landportal.org/library/resources/survey-country-gender-profile-kingdom-bhutan

[41] World Bank Group. (2020). Bhutan Systematic Country Diagnostic: Taking Bhutan’s Development Success to the Next Level. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-systematic-country-diagnostic

[42] World Bank. (2013). Bhutan Gender Policy Note. World Bank. https://landportal.org/node/32390

[43] Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2020). BTI 2020 Country Report Bhutan. Bertelsmann Stiftung. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bti-2020-country-report-bhutan

[44] World Bank Group. (2020). Bhutan Systematic Country Diagnostic: Taking Bhutan’s Development Success to the Next Level. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-systematic-country-diagnostic

[45] Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2020). BTI 2020 Country Report Bhutan. Bertelsmann Stiftung. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bti-2020-country-report-bhutan

[46] World Bank. (2019). Bhutan Forest Note: Pathways for Sustainable Forest Management and Socio-equitable Economic Development. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-forest-note

[47] JICA. (2017). Survey of Country Gender Profile (Kingdom of Bhutan). Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), IC Net Limited. https://landportal.org/library/resources/survey-country-gender-profile-kingdom-bhutan

[48] Pain, A., & Pema, D. (2004). The matrilineal inheritance of land in Bhutan. Contemporary South Asia, 13(4), 421–435.

[49] Tenzing, K., Millar, J., & Black, R. (2017). Changes in Property Rights and Management of High-Elevation Rangelands in Bhutan: Implications for Sustainable Development of Herder Communities. Mountain Research and Development, 37(3), 353–366.

[50] Lham, D., Wangchuk, S., Stolton, S., & Dudley, N. (2019). Assessing the effectiveness of a protected area network: A case study of Bhutan. Oryx, 53(1), 63–70. https://landportal.org/library/resources/assessing-effectiveness-protected-area-network-case-study-bhutan

[51] Sears, R. R., Phuntsho, S., Dorji, T., Choden, K., Norbu, N., & Baral, H. (2017). Forest ecosystem services and the pillars of Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness (Occasional Paper 178). Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). https://landportal.org/library/resources/handle1056895081/forest-ecosystem-services-and-pillars-bhutan%E2%80%99s-gross-national

[52] World Bank Group. (2020). Bhutan Systematic Country Diagnostic: Taking Bhutan’s Development Success to the Next Level. World Bank. https://landportal.org/library/resources/bhutan-systematic-country-diagnostic

Authored on

16 September 2021