Until now, a comprehensive study of national-level expropriation, compensation, and resettlement procedures in 50 countries across has not been conducted. My PhD research project, facilitated by the University of Groningen Faculty of Law, aims to bridge this gap by providing a broad comparative analysis of nation legal frameworks in 50 countries across Asia, Africa, and Latin America to determine whether legal procedures in these countries adopt internationally recognized standards on expropriation, compensation, and resettlement. The newest dataset on Land Book addresses whether laws require assessors to account for various tangible and intangible land values when calculating compensation, and whether there are legal processes in place that allow affected landholders to negotiate compensation amounts, receive prompt payments, and hold governments accountable by appealing compensation decisions in courts or before tribunals.

The legal indicators are based on the United Nations (UN) Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries, and Forests in the Context of National Food Security (2012) (the “VGGTs”). The dataset serves as a reference point and benchmark for progress in reforming expropriation, compensation, and resettlement laws. Through examining current statutory and regulatory compensation procedures, and highlighting whether those procedures adopt internationally recognized standards or “best practices”, the VGGT dataset seeks to inform legal and policy debates around the world.

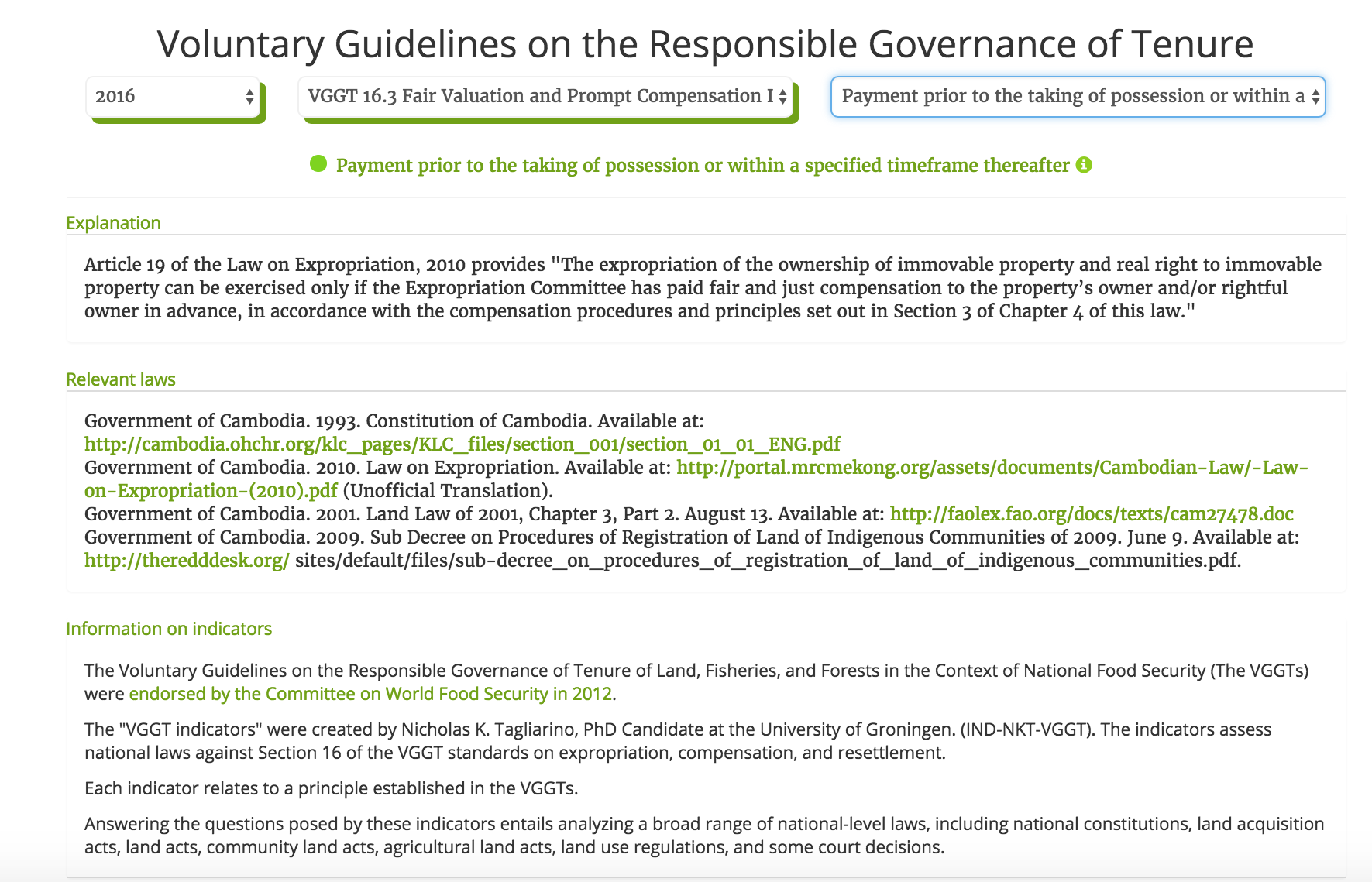

On Land Book, the VGGT dataset is displayed in a user-friendly infographic that provides links to the relevant laws, explanations of the legal indicator scores, and information on the legal indicators. The VGGT infographic now shows two datasets: one dataset on VGGT principle 16.1 (expropriation and compensation eligibility) and another dataset on VGGT principle 16.2 (fair valuation and prompt compensation). By clicking on the name of the indicator or holding the mouse over the small "i" button, one can see information on the legal indicators. Later this year, the infographic will show additional legal indicators on expropriation, compensation, and resettlement.

Background

Insufficient compensation can increase poverty levels, cause joblessness and hunger, tear apart social fabrics, and trigger conflicts. The combination of forced eviction and insufficient compensation may be particularly burdensome for poor and marginalized groups, such as Indigenous Peoples and local communities, who depend on their land for food, nutrition, income, traditional practices, and other basic needs. In many countries, the amount of compensation granted to affected populations is often insufficient to restore their livelihoods when land is taken for "public purposes" pursuant to expropriation laws. According to a UN Habitat study, the amount of compensation and resettlement assistance provided to affected populations in Cambodia, Indonesia, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines was not enough to cover their losses, allow them to purchase alternative land, and sustain an adequate standard of living after their land was expropriated. In China, a survey of 476 expropriation cases revealed that 65.5 percent of affected farmers were dissatisfied with the amount of compensation allotted. In Cambodia, failure to adequately compensate landholders affected by the construction of a railroad has recently led to impoverishment and unrest among landholders. The World Bank’s Land Governance Assessment Framework (hereinafter “LGAF”) found affected populations in Afghanistan, Brazil, Ethiopia, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania and other countries were not granted sufficient compensation in many cases. In Nigeria, for example, the LGAF study found “a large number of acquisitions occurs without prompt and adequate compensation, thus leaving those losing land worse off, with no mechanism for independent appeal even though the land is often not utilized for a public purpose.” The recurring problem of insufficient compensation begs the question of what can be done to diminish impoverishment risks and ensure affected populations are not worse-off than before land was expropriated.

Rule of law and good governance are essential “preconditions” for the satisfication of international standards, including the VGGTs and Sustainable Development Goals.[1] But the rule of law must provide people with clear and effective guidance.[2] In theory, if compensation procedures are designed to ensure a fair valuation of compensation which accounts for all of the losses borne by affected landholders, then the impoverishment and other risks associated with dispossession and displacement may be reduced. According to Cernea, “all forced displacements are prone to major socio-economic risks, but not fatally condemned to succumb to them.”

On the other hand, if compensation procedures contain gaps and ambiguities, there may be an increased risk that governments and acquiring bodies may expropriate land while paying insufficient compensation to affected landholders. Moreover, if decisions on compensation valuation are made in an ad-hoc or arbitrary manner then the rule of law may be contravened. Unless compensation procedures provide adequate redress mechanisms (e.g. a right to challenge compensation decisions in court or before a tribunal), affected populations may be unable to hold governments and acquiring bodies accountable for poor compensation decision-making.

Research Findings

An assessment of national-level compensation procedures in 50 countries across Asia, Africa, and Latin America reveals:

In most of the 50 countries assessed, compensation is based on the land's "fair market value" (FMV), which is commonly defined as the amount that a willing buyer would pay a willing seller on the open market where some choice exists. However, eight of the 50 countries[3] establish alternative approaches to the "fair market value" (FMV) approach to calculating compensation, which can be applied in cases where land markets are weak or non-existent. For example, Tanzania’s Village Land Regulations, 2001 provide “the market value of any land and unexhausted improvement shall be arrived at by use of a comparative method evidenced by actual recent, sales of similar properties or by the use of income approach or replacement cost method where the property is of a special nature and not saleable."[4] Similarly, in Sierra Leone, the “replacement cost” approach may be used to calculate compensation if the land is devoted to a purpose of such a nature that there is no general demand or market for land for that purpose.[5]

Alternatives to the FMV approach to valuing compensation may be needed in a variety of contexts. In many countries, accurately determining FMV is difficult if not nearly impossible. For instance, in many areas there are rural communities, including indigenous and local communities with customary tenure rights, who have lived on their land for centuries and never sold it. Some countries have laws that impose restrictions or limitations on the ability of rural landholders to sell their land, which further makes it difficult to ascertain the land’s market value. In India, for example, tribal landholders cannot accurately assess the FMV of land because restrictions on alienation have prevented tribes from selling their land since the 1970s.

Only two of the 50 countries assessed (India and Laos) have compensation procedures that partially protect women from expropriation without fair compensation. Compensation and resettlement procedures may disproportionately burden women landholders if procedures do not establish special protections ensuring women are sufficiently compensated. Women in rural areas play a crucial role in sustaining rural societies by caring for household members, attending to family vegetable gardens, feeding animals, collecting firewood, and supplementing income with jobs outside of the home. Yet, according to Landesa, women in more than half the world’s countries are denied the ability to own, inherit, or manage land by law or custom. The effect of gender-neutral compensation procedures, particularly in patriarchal societies, may be that compensation is paid only to the male head of household.[6] As discussed in the 2008 FAO study on compulsory acquisition and compensation, "if compensation is paid to the male head of the household, the needs of women and children may be ignored as the money vanishes, to the detriment of the family’s health and welfare."

Seven of the 50 countries provide compensation for community tenure rights regardless of whether those rights are formally registered or not. [7] For a discussion of why registration processes potentially put Indigenous Peoples and local communities at risk of expropriation without fair compensation, see the previous VGGT blog posted on Land Portal.

Twenty-six of 50 countries provide compensation for economic activities (e.g. business) associated with the land.[8]

Thirty-two of 50 countries have laws that provide compensation for improvements made on the land.[9] "Improvements" refers to the land's attached and unattached assets, including crops, buildings, and fixtures.

In addition to section 18.2 of the VGGTs, Article 5 of International Labour Organization Convention 169 (the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention) also calls for recognition of intangible, non-market values and states, “the social, cultural, religious and spiritual values and practices of [Indigenous and tribal peoples] shall be recognized and protected.” Moreover, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and IFC Performance Standard 7 indicate that ancestral territories and other lands used for religious, cultural, and traditional practices must be protected and respected. However, only two of 50 countries (Bhutan and the Philippines) have laws that explicitly require acquiring bodies to consider the land’s intangible land values (e.g. historical, cultural, spiritual values) when assessing compensation.[10] Eight of 50 countries received “partial” scores because their laws require assessors to account for intangible land values to some extent. However, these countries’ legal provisions do not ensure that intangible land values will be accounted for in every case.[11]

Nineteen of 50 countries have laws that provide affected populations with a right to opt for alternative land instead of or in addition to compensation. [12]

Twenty-one of 50 countries have laws that require governments to pay compensation before acquiring land or within a specified timeframe thereafter. [13]

Twenty-seven of 50 countries have laws that provide affected populations the right to negotiate compensation levels.[14]

Thirty-four of 50 countries have laws that grant affected populations the right to challenge compensation decisions in courts or before tribunals.[15]

*A forthcoming paper analyzes these findings in more detail.

A benchmark for progress

This dataset establishes a benchmark for progress to assist civil society organizations, NGOs, policymakers, land rights advocates, affected landholders, and other stakeholders in measuring government progress towards adopting VGGT standards on expropriation, compensation, and resettlement in domestic laws. In terms of compensation valuation, some countries, such as India, Laos, Philippines, Tanzania, Indonesia, and Cambodia, have enacted laws with relatively robust compensation procedures that largely adopt the VGGT standards on compensation. However, there is ample room for progress. In most of the 50 countries assessed, there are a number of gaps in national laws that put affected populations at risk of being insufficiently compensated upon expropriation. These legal gaps must be filled if national laws are to adopt the VGGT and other international standards on ompensation. Strong legal rights to fair compensation are necessary to ensure affected landholders are not worse-off than before their land was taken, but strong legal rights may be insufficient. Governments must also respect and enforce legal rights to compensation in order to afford protection to landholders affected by expropriation.

*It is important to note that the legal indicator scores are based on the written laws, and do not reflect how the laws operate in practice. I am continuing to update and refine the VGGT infographic. I welcome any feedback and suggestions on how to improve the infographic's usability and the information provided.

References

[1] Uygur, G. “The Rule of Law: Is the Line Between the Formal and the Moral Blurred?” in Law, Liberty, and the Rule of Law edited by Imer B. Flores and K. E. Hiima , Springer Publishing, New York, 2013, p. 119.

[2] J. Raz, ‘The Rule of Law and Its Virtues in The Authority of Law: Essays on Law and Morality, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1979, pp. 210, 213, 218; Dagan, H. Expropriatory Compensation, Distributive Justice, and the Rule of Law in Rethinking Expropriation Law I: Public Interest in Expropriation edited by B. Hoops, E. J. Marais, H. Mostert, J.A.M.A. Sluysman, and L.C.A. Verstappen. Den Haag, The Netherlands: Eleven International Publishing. Dagan notes that “at times, commitment to the rule of law implies allowing, or even preferring, that the social practice of a legal topic be formed around a vague but informative standard….[but] by contrasts, open-ended references to justice, fairness, good faith, or reasonableness….fail to ensure proper predictability or properly constrain law appliers. They should therefore be criticized as a n invitation to ad hoc discretion, which affronts the rule of law.”

[3] Belize, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Ghana, Laos, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tanzania

[4] Government of Tanzania. 2001. Village Land Regulations, Sec. 10.

[5] Government of Sierra Leone. 1960. Public Lands Ordinance, Ch. 116 (1960), Section 18(1)(g).

[6] United Nations. 2013b. “Realizing Women’s Rights to Land and other Productive Resources.” HR/PUB/13/04. New York, NY and Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/realizingwomensrightstoland.pdf

[7] Laos, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia

[8] Afghanistan, Angola, Bangladesh, Belize, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, China, Ethiopia, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Laos, Mexico, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Taiwan, Tanzania, Trinidad and Tobago, Vietnam, Zambia, Zimbabwe

[9] Bangladesh, Belize, Botswana, Brazil, Cambodia, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Laos, Lesotho, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Peru, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Tanzania, Thailand, Vietnam

[10] According to Bhutan’s Land Act, 2007, for example, “the valuation of the land and property shall consider…other elements such as scenic beauty, cultural and historical factors, where applicable." The Philippine’s Indigenous People’s Rights Act, 1997 helps ensure that compensation payments reflect the historical/cultural connections associated with land. In addition to establishing special protections for ancestral lands held by Indigenous Peoples, the Act establishes an Ancestral Domains Fund, which can be used to compensate Indigenous Peoples when their ancestral domains are expropriated.

[11] Article 20(3) of the Ghana’s Constitution, for example, requires that "where compulsory acquisition or possession of any land effected by the State...involves displacement of any inhabitants, the State shall resettle the displaced inhabitants on suitable alternative land with due regard for their economic well-being and social and cultural values." However, Ghana received a "partial" score because Ghana has not passed legislation or regulations, which provide procedures for implementing this provision.

[12] Afghanistan, Cambodia, Eritrea, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Laos, Mongolia, Nepal, Nigeria, Philippines, Rwanda, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Vietnam, Zambia

[13] Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Botswana, Cambodia, Ecuador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Laos, Lesotho, Mexico, Philippines, Rwanda, Swaziland, Taiwan, Thailand, Uganda, Vietnam, Zimbabwe

[14] Argentina, Belize, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, China, Eritrea, Ghana, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Laos, Malaysia, Mongolia, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Vietnam, Zambia

[15] Argentina, Bangladesh, Belize, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, China, Ecuador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Honduras, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Laos, Liberia, Malaysia, Mongolia, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Uganda, Zambia

For country scores, explanations, and relevant laws, see Land Book.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the Land Portal team, in particular Marcello Demaria, Carlos Tejo, and Jules Clement, for their invaluable support in developing the VGGT infographic. If you have any questions or comments on the dataset, please contact nicholas.tagliarino@landportal.info. Also, please contact me or marcello.demaria@landportal.info if you are interested in linking open access data to the Land Portal. The Land Portal Research Unit can support organizations in curating their qualitative and quantitative data to make it user-friendly and easy to access on Land Portal.