By Rick de Satgé (Land Portal), reviewed by Joseph Holenu Mangenda, Associate Professor at the University of Kinshasa

The DRC has been described as “a rich country of poor people”1. It covers an area of 2,345,410 km². It has a population of some 89 million people and a surface area equivalent to that of Western Europe. It is the largest country by area in sub–Saharan Africa. Four national languages are recognised, but overall, more than 200 languages are spoken within its borders, albeit with varying reaches2.

While it is clear that there are deep seams of conflict shaping the history of the DRC, it has been argued that it is misleading to make this the primary lens through which to view land and resource disputes. Rather these need to be understood in relation to accelerating structural processes of exclusion and dispossession.

Deforestation near Weko, DRC. Photo by Axel Fassio, CIFOR, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license

The DRC shares borders with nine neighbouring states, of which two to the north – the Central African Republic and South Sudan have been characterised as collapsed states3. The Great Lakes region to the East which includes Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi have long been zones of high conflict and instability. Large numbers of people displaced by conflicts in the Great Lakes region cross borders, raising tensions and driving up competition for land and other resources.

Camps for people displaced by conflict in North Kivu. Photo by Marie Frechon, UN Photo, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license

According to the UNDP HDI index the DRC is one of the poorest nations in the world. DRC GDP per capita was ranked 11th lowest in the world in 20194. It ranks 112 out of 113 in the Global Food Security Index. It is one of the most mineral rich countries on the planet with huge reserves of gold, copper, diamonds, oil, uranium, manganese, silver and tin as well as the largest deposits of cobalt and coltan globally. It has been estimated that the DRC has untapped mineral reserves worth an estimated $24 trillion5. At the same time DRC has a tropical forestry potential second only to Brazil6. Despite this mineral and natural resource wealth, the country displays all the features of the so-called ‘resource curse’7, where instead of contributing to economic growth, mineral and forest riches have fuelled localised conflicts, enabled the growth of powerful elites and created conditions of super exploitation of conflict minerals, often involving child labour.

Artisanal cobalt mining. Photo by Afrewatch IIED CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license

The country has endured recurrent cycles of violence throughout its history. These commence with the impacts of slavery which segued into the private plunder of King Leopold and subsequent Belgian colonial rule, characterised by extreme brutality. This was punctuated by a brief democratic interlude following independence. However, this was brought to an abrupt close by the execution of Patrice Lumumba – the first Prime Minister. The country was then ruled for 32 years by Mobutu Sese Seko who seized power following a military coup in 1965. From the mid-1990s-2003 the DRC experienced unparalleled instability. In the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide, Interahamwe militia, along with hundreds of thousands of refugees fled into the eastern DRC. The complex national and regional conflict and its impacts on access to land, livelihoods and food security, and utilisation of forest and mineral resources can only be briefly described within this short country profile.

Waves of conflict have resulted in the multiplication of scores of armed militias. The cumulative death toll spanning different historical periods – from the Congo, post-independence to Mobutu’s renamed Zaire and the DRC of the Kabila era, is now reported to be in excess of 5 million lives. In February 2021, the World Food Programme reported that there were 5.2 million internally displaced people in the DRC and 19.6 million people in need of humanitarian assistance. This situation was further exacerbated by the spread of Covid-19, although the impact of this has yet to be assessed.

Historical backdrop

In 1870 the vast majority of sub-Saharan Africa was still governed by diverse African polities. In the Congo basin such polities had a long history. Large parts of eastern Congo were characterized by stratified social structures which regulated access rights to customary-held land in return for rent8.

As early as the 1300’s the Kongo Kingdom straddled territory in contemporary northern Angola and Western Congo, as well as central Katanga. This remained a coherent social force for around 500 years. The arrival of Portuguese navigators at the mouth of the Congo River in the 1480s prefaced the transatlantic slave trade. Between 1500 and 1800 an estimated 5 million people were enslaved across the Congo basin. The slave trade involved lucrative deals between Kongo intermediaries and a succession of Portuguese, Dutch, French and other slavers. The slave trade created deep social fault lines in Congolese society which the Portuguese entrenched by seeking to instal pliant rulers. A strategy of divide and rule and shifting alliances has characterised subsequent colonial and post-colonial interventions.

In 1884 Belgian King Leopold authored a unique chapter in global colonial history, establishing himself as the ‘proprietor’ of a vast private colony known as the Congo Free State. Here, he set about hunting for ivory and establishing rubber plantations. Leopold’s 19,000 strong private army, the Force Publique policed this trade, implementing systems of forced labour marked by extraordinary brutality. An estimated ten million people – half the population of the Congo – died between 1880 and 19209.

Following public exposure of widespread atrocities committed by his agents, the Belgian King decided to sell off ‘his’ colony to the Belgian state. Throughout its rule the Belgian government implemented a strict system of racial segregation and persisted with systems of forced labour, which required all Congolese to work 60 days a year. In the early part of the 20th century Belgian colonial rulers began to exploit the

Congo’s valuable mineral resources, commencing with industrial scale copper production in Katanga province in 1913. Following a protest strike in 1941, which was harshly repressed by Belgian colonial authorities, the Belgian government doubled the number of days Congolese were required to work to 120 days a year.

In 1959 urban riots and mounting resistance to colonial rule countrywide pushed the Belgians into hurriedly granting independence to an unstable coalition government. In 1960, Joseph Kasavubu was installed as President and Patrice Lumumba – leader of the emergent nationalist movement, as Prime Minister. Joseph Mobutu, a former soldier in the Force Publique was appointed Secretary of State for Defence. Within days of the independence ceremony, the Congolese army had mutinied against its Belgian officers, while a Belgian backed secessionist movement pushed for independence for the mineral rich Katanga province. The resultant Congo crisis prompted UN intervention. Mobutu briefly seized control of the government and arrested Prime Minister Lumumba, who was flown to Katanga and summarily executed, with the complicity of the Belgian and U.S governments10. Mobutu, who initially restored the government to President Kasavubu, was appointed Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces – a position which enabled him to lead a military coup to seize and retain political power in 1965.

Throughout his 32-year rule, Mobutu received support from the United States and other western countries, despite promulgating the Bakajika Law in 196611, which was aimed at undoing colonial concessions granted before independence and nationalising mines and businesses for a period. However, the combination of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, which ended the Cold War, and Mobutu’s default on international loans, prompted a US policy shift. Mobutu came under pressure to open up Zaire to multiparty democracy. In 1998 a transitional government was appointed and the ban on multi-party politics was lifted. At the same time the country began to suffer from massive inflation which reached 8000% on a yearly basis.

In 1994, Zaire experienced major impacts from the deep-seated conflicts in neighbouring Rwanda, a small country first colonised by the Germans as part of German East Africa. After Germany was defeated in World War I, Belgium was given a mandate to administer both Rwanda and Burundi. Belgian social engineering and promotion of perceived ethnic identities, served to enlarge social differences and entrench fundamentally unequal relations of power between people in a densely populated and land hungry country. Belgian social policy partially fabricated and actively favoured a Tutsi minority and discriminated against the Hutu majority. However, in the late 1950’s, just a few years prior to Rwandan independence, Belgian policy underwent a polar shift in favour of the Hutu majority. These interventions generated rolling cycles of conflict and displacement in the region, swelling a massive refugee population, leading to uprisings and invasions, and laying the groundwork for the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

The Interahamwe Hutu militia killed an estimated 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu who favoured peaceful relations with their neighbours. Tutsi rebels of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) overthrew the Hutu government and took control of the country, prompting between one and two million Hutu to flee. The majority of Hutu refugees crossed the border into Zaire around Northern Kivu, while others sought refuge in camps across the region in Tanzania, Uganda, Congo-Brazzaville, and the Central African Republic.

Following their expulsion, Interahamwe militia based in Zaire, terrorised the local population and carried out cross border raids into Rwanda. This prompted the Congolese Banyamulenge Tutsi, resident in Eastern Zaire, to rise in a bid to force the Rwandan Hutu out of the country. The Rwandan and Ugandan armies invaded the DRC in support of the uprising, while backing an anti-Mobutu rebel group led by Laurent Kabila. As the invading force advanced on Kinshasa, Mobutu fled the country, never to return.

After Kabila was installed as president in 1997, he pressed for the withdrawal of foreign forces from the DRC, while allowing Hutu militia to regroup in the Eastern DRC. This prompted renewed resistance by the Banyamulenge and prompted a second invasion by Rwandan and Ugandan forces now in opposition to Kabila’s government. Laurent Kabila was assassinated in 2001 and was succeeded by his son.

The conflict in the DRC rapidly escalated into a five-year Second Congo War. This involved troops from Zimbabwe, Namibia and Angola fighting alongside Kabila’s armed forces in the DRC to repel Rwandan and Ugandan forces. The conflict provided a gateway for military linked entrepreneurs to profit from the militarisation of mining and timber extraction and associated opportunities of a war economy12, while fostering the rise of hundreds of armed militias.

A combination of external intervention and internal negotiations finally resulted in an agreement on power sharing arrangements and a transitional constitution in 2003 which limited the office of future Presidents to two terms. However, despite these agreements Joseph Kabila, who was due to step down in 2015, sought to extend beyond his second term unilaterally, prompting violent protests. Elections in 2018 were won by an opposition candidate Felix Tshisekedi, but allegations have been made that the results were manipulated, following a behind the scenes power sharing deal to ensure protection of the former president’s interests after 18 years in power13.

Conflict remains a feature of daily life in parts of the DRC with most of the fighting taking place in the Eastern DRC and North and South Kivu, adjacent to the DRC/Rwanda border. “The presence of foreign forces and militia groups, based in ‘‘the unoccupied spaces’’, with the capacity to threaten or destabilise either the DRC or neighbouring states remain the single most important dimension of the protracted instability”14.

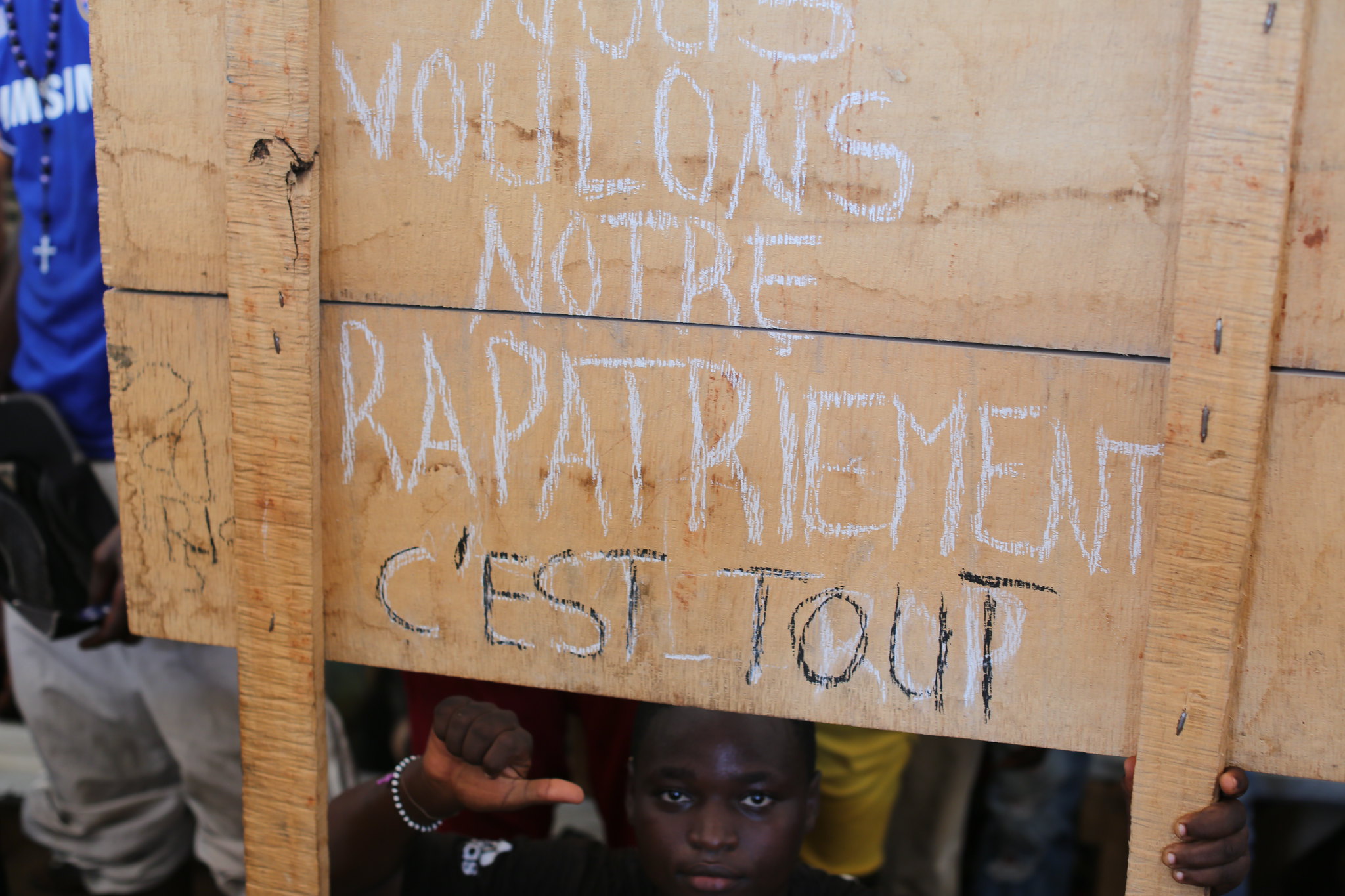

Refugee demands. Photo by Myriam Asmani, CC BY 2.0 license

While it is clear that there are deep seams of conflict shaping the history of the DRC, it has been argued that it is misleading to make this the primary lens through which to view land and resource disputes. Rather these need to be understood in relation to accelerating structural processes of exclusion and dispossession.

“Behind the more ‘spectacular’ manifestations of violence, less visible processes of rural differentiation may unfold in which the interests of landed elites and the rural poor increasingly diverge. This deepens existing inequalities and leads to multiple forms of dispossession”15.

Land legislation and regulations

During the colonial period, a dual land-system was installed in which state law governed state land (terres domaniales), and customary law governed indigenous land (terres indigènes)16. “There was a de jure recognition of customary land tenure, but colonial interests always overruled local ones”17.

Shortly after independence in 1966, the Congolese government promulgated the Bakajika Law, which was aimed at undoing colonial concessions granted before independence18 and imposed a requirement of 100% Congolese ownership of all farming, industrial and other enterprises.

“The new land law system effectively continued the colonial system of land control, which enabled state ownership of all wealth ‘above and below’ the ground, thereby ensuring that public mineral (and oil) rights went to the government”19. As a result foreign mining companies withdrew their investment, and many enterprises were bankrupted.

In July 1973, the General Property Law was enacted as part of the country's new legal framework concerning land issues. These laws meant that all land now belonged to the state, and individual land rights had to derive from either state concessions, or indigenous systems of customary law20.

The 1973 Act created uncertainty around the legal status of land occupied by communities and indigenous people, “providing that usufruct rights acquired according to custom would be settled by order of the President of the Republic. This order was never signed”21. “Since 1973, the legal status of customary tenure rights has, to say the least, been highly ambiguous”22.

Village near Yangambi, DRC. Photo by Axel Fassio, CIFOR, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license

A Forestry Law passed in 2002 created a legal framework for community owned and managed forest areas – but these only recently materialised in 2016, through regulations which enable communities to apply for customary ownership rights on forest areas, not exceeding 50,000 ha.

The 2006 Constitution provides the state with sovereignty over land resources and guarantees individual and collective land rights, together with those of women. However, the realisation of these rights remains remote.

An Agricultural Law passed in 2011 restricts land ownership to those of Congolese nationality but has yet to be implemented in practice. It also reportedly remains vague with respect to customary land holdings and fails to practically advance women’s land rights23.

In 2011 President Joseph Kabila announced the need to “put the DRC on the path to modernity”. He identified the need to bring about land reform in order to create an environment conducive to socio-economic development and to reduce tensions around land. A national land reform commission (CONAREF) was established to oversee the process24. However it has been noted that these developments took place against a background of political turmoil and were practically subjugated by other government priorities25.

In July 2012, the Ministry of Land Affairs with the support of some partners (e.g., Comité de Pilotage de la Réforme des Entreprises du Portefeuille de l'Etat-COPIREP, Rights and Resources Initiative-RRI, UN Habitat) initiated a national dialogue on land tenure through a three-day workshop, bringing together all provincial and national stakeholders. A consensual roadmap for an inclusive and participatory reform was reported to have resulted from this process. The roadmap sought to guide the land reform process in the DRC through the drafting of an appropriate land policy; extensive legal reform; the clarification of institutional responsibilities along with an implementation and related capacity development programme.

The roadmap also identified the need for improved and decentralised land governance to strengthen the business climate. This reflected DRC’s intention to become a signatory to the OHADA Treaty of 1993, under which fourteen countries from West and Central Africa agreed to harmonise their legal systems in the area of business law26. The road map also emphasised the need to clarify the role and status of customary leaders and develop alternative mechanisms for the prevention and resolution of land conflicts.

A baseline study on land governance completed in 2013 with funding from the World Bank and Belgium recommended:

- establishment of a multi actor platform to harmonise policies across government;

- piloting data collection as the basis for land reform and to simplify processes for issuing certificates/titles;

- demarcating of fields/forest/community land mapping;

- the codification of local land rights.

Given the turbulent history outlined above, in practice there has been little sustained attention paid to the elaboration of land law, tenure security and land rights management in the DRC. Concerns have been expressed handed over design and implementation of the land reform process to donors while placing CONAREF staff under the administration of UN-Habitat. Relations between donors, UN agencies and local organisations are characterised by competition and weak coordination27. To date the DRC has not yet finalised a land policy, or a system of land use planning28.

Land and natural resources remain vested in the state or are allocated informally through customary law. However, there is mounting evidence that opportunistic customary leaders manipulate land allocations to their personal benefit, or for patronage purposes29.

Overall, land reforms remain very slow moving in the DRC. Despite the delays, local actors are reported to recognise that a participatory and consensual land reform at the national level could greatly contribute to the pacification and reconstruction of the country. There are also expectations that a land tenure system capable of securing the rights of individuals and local communities while guaranteeing a favourable environment for investment would be conducive to economic and social development, as set out in the GPRSP9 and in the MDGs.

There are recent reports of provincial land policy consultations countrywide which are intended to help shape policy development and prepare for the drafting of a new law30, while local and international organisations have invested in systems to locally manage land rights, issue certificates and address land conflicts, with very mixed results. Many of these externally driven initiatives have still to be legitimated by the state.

Land tenure classifications

The land sector in the DRC has been usefully characterised as a complex hybrid space in which “diverse and competing governance structures, sets of rules, logics of behaviour, and claims to power co-exist, overlap, interact, and intertwine in the access to and control over resources”31.

De jure, the 1973 land law is still in force, but has since been amended by the 2006 constitution so that the state retains sovereignty over all land, as opposed to ownership. Individual land rights derive from either state concessions or indigenous customary law – itself of uncertain status and highly contextually specific. In practice however 70% of land is held and allocated under customary tenure32.

Due to the frequently opaque nature of land acquisition, land disputes are ubiquitous and where rights of different ethnic groups become contested, these disputes can easily spiral into violence33.

Community land rights issues

There have been some recent initiatives to promote localised land rights and promote decentralised land governance systems in the DRC, based on issuing certificates of customary ownership. Several national and international organizations and UN agencies are involved in various individual and collective land formalization processes, with the support of some donors34. However, these initiatives remain poorly coordinated and weakly supported by the state.

A mosaic of forests and fields. Photo by CIFOR CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license

Overall, community rights to land and forest resources remain under threat and vulnerable to land grabs often linked to mining and logging, although the extent of this will vary widely across the different districts. The imprint of armed conflict is evident in major social and environmental impacts across the DRC. In conflict prone districts people living in fear of militia attacks relocate to seek security in the core forest. This increases household dependence on natural resources, while simultaneously accelerating forest fragmentation. Similarly, the movement of hundreds of thousands of refugees and internally displaced people has exacerbated local land and resource conflicts and undermined local land rights institutions. This has also contributed to forest loss and degradation, as refugees are forced to rely on forest resources and shifting cultivation to sustain their livelihoods35.

Land use trends

The Congo basin contains the second largest and least degraded area of equatorial rainforest in the world. which is 2 million square kilometres in extent. The Congo forests have been described as the lanet’s “second lung and contains approximately 8% of global forest-based carbon36. However, a range of factors threaten this resource which is of global importance.

Both artisanal and large-scale logging and mining are increasingly understood to have impacts which can radiate far beyond the footprint of the land directly impacted by the activity. Mining can result in radical changes in the areas where minerals are found. For example, in the Tenke Fungurume mine in the southeast of the country the region’ population “trebled virtually overnight”37. Rapid population changes impact on land uses and land rights. Frequently the artisanal and commercial logging and mining sectors find themselves in fierce competition with each other. In 2019 state security forces expelled 10,000 artisanal miners reported to be encroaching on two of the largest industrial mining sites in Haut-Katanga and Lualaba provinces38.

Artisanal Coltan mining. Photo by Sylvain Liechti, MONUSCO, CC BY 2.0 license

The establishment of palm oil and eucalyptus plantations have also resulted in major changes of land use. Overall, however shifting cultivation remains the primary proximate driver of deforestation39.

The DRC has established numerous protected areas including Garamba, Virunga, Maiko, Upemba and Salonga national parks – several of which have World Heritage status.

Many people in urban areas in DRC use wood and charcoal for cooking which places pressure on forest resources particularly in peri urban areas. Forests within a 50 km radius of the metropolitan Kinshasa – home to an estimated 15,6 million people have been depleted. Firewood collection has been estimated to lead to the deforestation of 60,000 ha a year in the DRC40.

Informal charcoal production. Photo by Axel Fassio, CIFOR, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license

REDD+, a UNFCCC Conference of the Parties framework adopted in 201341 aims to curb deforestation and habitat reduction and allows countries to seek and obtain results-based payments. Notionally this should provide a source of income for community resource users and managers, although this has been criticised for enabling ‘green grabbing’42 and has opened doors to elite capture of benefits.

Land investments and acquisitions

Foreign land acquisition in the DRC is significant, although significantly less than originally projected in the literature published on ‘the global land rush’43. In late 2019, there were reported to be 53 deals in the DRC across all land uses, involving an estimated 7.5 million ha of land. These fall into four categories – logging projects, mining concessions, agricultural business parks, together with land acquisitions made by domestic companies and individuals44. However it is uncertain how much of the land nominally allocated is actually used.

Much of the large-scale logging in the DRC does not meet legal requirements, which include an approved management plan. “More than 30 of the current 57 legally issued large-scale logging concessions in DRC, covering just over five million hectares, have no valid management plan more than five years after their concession contracts were signed”. In 2014 it was reported that 90% of logging in the DRC was illegal or informal, supplying domestic and regional markets. The actual log harvest in the DRC was estimated to be around eight times the official harvest45.

Cutting timber. Photo by Axel Fassio CIFOR, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license

In 2018, two Chinese companies were reported to have been allocated logging concessions in environmentally sensitive equatorial forest areas, despite a moratorium on new logging contracts. Laterin the year a representative of the Chinese logging company ‘Maniema Union 2’ was reported to have been arrested on charges of illegal logging. However, in May 2019 the company was reportedly acquitted after payment of a “transactional fine”46.

Large agricultural estates like the Feronia palm oil plantation, involve land leases issued over more than a 100,000 ha of land. There has been ongoing tension with villagers in the concession area over land rights, with violent confrontations reported in 201947. There are suggestions that companies involved in plantation agriculture may collude with logging companies to expand palm plantations into logged areas, thereby changing land uses48.

A mining code was developed in 2002 which sought to incentivise foreign investment. The code is silent on the status of customary land rights in relation to mining. Mining was extensively militarised in the Eastern DRC as a consequence of armed conflict and civil war49. Mining activities have expanded rapidly since the second Congo war, with large multinational companies investing in the DRC. Where mineral rights have been allocated to foreign companies, community rights and those of artisanal miners have frequently been overridden without compensation being paid50. Exploitative working conditions have been reported across the mining sector in the DRC. Child labour has been documented in the cobalt mining segment. In 2019 a precedent setting legal case was filed in the US by Congolese families, accusing the world’s largest tech companies Apple, Google, Dell, Microsoft and Tesla of complicity in the death, or maiming of their children employed to mine for cobalt, used to power smartphones, laptops and electric cars51.

Extensive research has been carried out on how profits from the mining industry have been appropriated by predatory elites and their allies in the DRC52. In 2018 the “wide spectrum of corruption in the cobalt trade, combined with abuses at and around cobalt mine sites and links to state-sanctioned violence and grand corruption” was characterised as forming “a crucial pillar in Congo’s violent kleptocratic system”53.

Prospecting is also threatening biodiversity. In 2018 oil companies were granted exploration rights which include rights to prospect in portions of two key national parks.

With regard to agricultural land, there have been numerous grand plans to kick start a ‘modern agricultural sector’ and ‘transform’ Congolese agriculture. The National Agricultural Investment Plan developed in 2013 sought to issue leases on 21 massive agribusiness parks, totalling more than a quarter of the total land area in the country. “The first agro-industrial park was conceived as a pilot project in Bukanga Lonzo, some 260 km southeast of the capital Kinshasa. It was set up through a public-private partnership between the government and a South African company, on 80,000 ha of land for the production of corn and other agricultural commodities”[54]. The pilot collapsed in 2017 and the South African company launched a court action for non-payment of their expenses.

Women’s land rights

Woman clearing land. Photo by Kjersti Lindoe, Norad, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license

Women’s land rights, although protected by the 2006 Constitution, remain vulnerable in practice. In 2012 following a national workshop on land reform the state undertook to better protect land rights of individuals and legal entities, both public and private, with particular attention to vulnerable populations and women55. Numerous donor funded programmes in the DRC have focused on the formalisation of land rights, which have included a focus on women. For example, in Kalehe, a donor organisation is reported to have paid for and granted householders, including hundreds of women, attestations pour l’occupation et l’exploitation d’un terrain coutumier (certificates for the occupation and exploitation of customary land). There is also some evidence – though largely anecdotal – of women being better enabled to claim inheritance rights and secure rights in land.

Overall recent research highlights “a deep gap in the way policy makers, donors, and local actors understand the concept of land security”56 and this extends to approaches to address the land rights of women.

Urban tenure issues

The population of Kinshasa, the capital, has doubled every five years since 1950 and currently stands at 15,6 million. It is one of the top five most populous cities on the African continent. Toward the mid-1990s, only 5%–10% of Kinshasa’s population was estimated to participate in the formal economy, a situation that “condemned everybody else to the “informal” survival strategies and the small-scale corruption”57. Conflict and forced displacement had led to rapid and unplanned urbanisation. Informality is the sole land and housing access option for the vast majority of the urban population. The World Bank estimates that more than half the peri-urban land in the DRC is under informal tenure58. Other sources suggest that this may be an underestimation.

Kinshasa street scene. Photo by Steve Evans, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license

“Dynamics of war, military interventions as well as humanitarian- and peacebuilding interventions have introduced a variety of ‘new’ actors such as armed groups, formal and informal protection entrepreneurs, self-defence groups, peace-keeping forces and humanitarian agencies to practices of urban governance”59. This has resulted in the creation of multiple zones and sites of power, characterised by locality focused systems of informal land allocation and dispute resolution.

In the Eastern DRC conflict economies have transformed urban centres along the borderlands with Rwanda and Uganda into “booming cross-border trading hubs and central nodes in (political) economic networks that connect the mineral-rich Congolese hinterlands to the global markets”.

Timeline - milestones in land governance

1500 - 1800 - An estimated 5 million people are enslaved to feed the transatlantic slave trade. Slavery aggravates local political rivalries and escalates social conflict.

1884 - King Leopold creates a private colony Congo Free State and appoints himself as ruler.

1908 - King Leopold sells the Congo to the Belgian state.

1959 - Anti-colonial riots in Kinshasa fuel demand for independence from Belgium.

1960 - The Congo achieves independence, but is immediately propelled into conflict, power and succession struggles.

1961 - Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Congo is dismissed by the President, abducted and executed with the collusion of Belgium and the United States.

1965 - General Mobutu seizes state power in a coup to rule for 32 years.

1966 - The Congolese government promulgates the Bakajika Law to nationalise mines, estates and enterprises.

1971 - Mobutu renames the Congo Zaire.

1973 - The Land Law is passed. All lands now belonged to the state, and individual land rights have to derive from either state concessions or indigenous customary law.

1990 - The US, a long-time supporter of Mobutu, applies pressure for a transition to multiparty politics.

1994-1996 - The Rwandan genocide leads to a massive influx of refugees and armed militia leading to regional instability and war.

1997 - Rwandan and Ugandan troops invade Zaire in alliance with AFDL rebels led by Laurent Kabila to overthrow Mobutu. Kabila is declared President and Zaire is renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

1998-1999 - Kabila switches allegiance, triggering Second Congo war which draws in troops from multiple African nations before a first ceasefire agreement is signed in August 1999. The war results in millions of deaths and internally displaced people and involves plunder of mineral and forest resources.

2001 - Laurent Kabila is assassinated and is succeeded by his son Joseph. The UN panel of Experts on Illegal Exploitation reports that the Congo war has evolved into a conflict for access and control over minerals.

2002 - The DRC introduces a new mining code consistent with the World Bank’s 1992 strategy for Africa mining.

2006 - New Constitution is promulgated.

2011 - President Kabila announces that land reform is a priority for the Congolese government.

2012 - DRC announces a process of land reform and establishes CONAREF – the national land reform commission.

2012-2021 - The Ministry of Land Affairs experiences eight changes of Minister undermining the land reform process.

2013 - National Agricultural Investment Plan proposes issuing leases for 21 massive agribusiness parks.

2017 - Pilot agribusiness park collapses.

2018 - Two Chinese companies were reported to have been allocated logging concessions in environmentally sensitive equatorial forest areas. Oil companies are granted exploration rights which include rights to prospect in portions of two key national parks. Widely reported abuses occur in the mining sector – particularly involving child labour and exploitative working conditions.

2019 - Precedent setting legal case was filed in the US by Congolese families suing the world’s largest tech companies for the death or maiming of their children employed to mine for cobalt. A total of 53 land deals are reported in the DRC across all land uses involving an estimated 7.5 million ha of land.

Where to go next?

The author's suggestion for further reading

The history of the DRC and its place in the politics of Central Africa is probably unparalleled in its complexity. Unfortunately, many key resources on its history are out of print and unavailable online. These include much of the wide-ranging work by Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, and Adam Hothschild60. A recent illustrated guide to the history of the Congo has been prepared by Salim Baraza for the Africa report.

Key contemporary resources relating to land issues include the analysis by Chris Huggins61 of the domestic and foreign land rush in the DRC, while David Betge62 and Bisoka and Claessens63 review land tenure and governance issues. The writings of anthropologist Filip de Boeck provide important insights into Congolese society and city life. Human Rights Watch has published several reports on the troubled mining sector, along with several others cited in the references. Theodore Trefon64 provides valuable analysis of the DRC’s environmental paradox, illustrating how a resource rich country remains one of the world’s poorest and most conflicted nations.

References

[1] Trefon, T. (2016). Congo's Environmental Paradox: potential and predation in a land of plenty, Zed Books Ltd.

[2] Translators without borders. (2021). "Language data for the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)." Retrieved 6 March 2021, 2021, from https://translatorswithoutborders.org/language-data-for-the-democratic-republic-of-congo-drc/.

[3] Rupiya, M. (2018). "What Explains President Joseph Kabila’s Quest for a Third Term until Pressured to Reluctantly Relinquish Power, late in 2018?" International Journal of African Renaissance Studies - Multi-, Inter- and Transdisciplinarity 13(2): 42-58.

[4] UNDP. (2019). "DRC Human Development Indicators." Retrieved 3 March, 2021, from http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/COD.

[5] USAID. (2018). "“The Dream” of a Responsible Minerals Trade in the DRC Becomes a Reality." Landlinks Retrieved

[6] Mpoyi, A. M., F. B. Nyamwoga, F. M. Kabamba and S. Assembe-Mvondo (2013). The context of REDD+ in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Drivers, agents and institutions, CIFOR.

[7] Papyrakis, E. and R. Gerlagh (2004). "The resource curse hypothesis and its transmission channels." Journal of Comparative Economics 32(1): 181-193.

[8] Vlassenroot, K. (2005). "Households land use strategies in a protracted crisis context: land tenure, conflict and food security in eastern DRC." Conflict Research Group, University of Ghent.

[9] Lowes, S. and E. Montero (2020). Concessions, violence, and indirect rule: Evidence from the Congo Free State, National Bureau of Economic Research.

[10] US Senate (1975). Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders.” In Declassified Interim Report with respect to Intelligence Activities. S. C. t. S. G. Operations. Washington DC, US Government.

[11] De Boeck, F. (2020). "Urban expansion, the politics of land, and occupation as infrastructure in Kinshasa." Land Use Policy 93: 103880.

[12] Nest, M. (2001). "Ambitions, Profits and Loss: Zimbabwean Economic Involvement in the Democratic Republic of the Congo." African Affairs 100(400): 469-490.

[13] Engelbert, P. (2019). "Congo’s 2018 elections: An analysis of implausible results." African Arguments https://africanarguments.org/2019/01/drc-election-results-analysis-implausible/ 2021.

[14] Rupiya, M. (2018). "What Explains President Joseph Kabila’s Quest for a Third Term until Pressured to Reluctantly Relinquish Power, late in 2018?" International Journal of African Renaissance Studies - Multi-, Inter- and Transdisciplinarity 13(2): 42-58.

[15] van Leeuwen, M., G. Mathys, L. de Vries and G. van der Haar (2022). "From resolving land disputes to agrarian justice–dealing with the structural crisis of plantation agriculture in eastern DR Congo." The Journal of Peasant Studies 49(2): 309-334.

[16] Bisoka, A. N. and K. Claessens (2019). "Real Land Governance and the State: Local Pathways of Securing Land Tenure in Eastern DRC." Negotiating Public Services in the Congo State, Society and Governance: 190-213.

[17] Ibid.

[18] De Boeck, F. (2015). "“Poverty” and the politics of syncopation: urban examples from Kinshasa (DR Congo)." Current Anthropology 56(S11): S146-S158.

[19] Ibid.

[20] De Boeck, F. (2020). "Urban expansion, the politics of land, and occupation as infrastructure in Kinshasa." Land Use Policy 93: 103880.

[21] Rukundo, T. and D. Betge (2020). The land reforms in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Coordinates. Netherlands.

[22] Bisoka, A. N. and K. Claessens (2019). "Real Land Governance and the State: Local Pathways of Securing Land Tenure in Eastern DRC." Negotiating Public Services in the Congo State, Society and Governance: 190-213.

[23] Huggins, C. (2021). Overlaps, Overestimates and Oversights: Understanding Domestic and Foreign Factors in the Land Rush in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Transnational Land Rush in Africa: A Decade After the Spike. L. Cochrane and N. Andrews. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 235-260.

[24] Mudinga, E. M. and C. I. Wakenge (2021). Land Crisis and Stakeholders’ Responses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Congo Research Briefs Issue 9, SSRC, Governance in Conflict Network, GEC-SH, CRG and CRP.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Kahindo, N. A. (2014). International sales contracts in Congolese law: a comparative analysis.

[27] Mudinga, E. M. and C. I. Wakenge (2021). Land Crisis and Stakeholders’ Responses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Congo Research Briefs Issue 9, SSRC, Governance in Conflict Network, GEC-SH, CRG and CRP.

[28] Huggins, C. (2021). Overlaps, Overestimates and Oversights: Understanding Domestic and Foreign Factors in the Land Rush in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Transnational Land Rush in Africa: A Decade After the Spike. L. Cochrane and N. Andrews. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 235-260.

[29] Claessens, K., E. Mudinga and A. Ansoms (2014). "Competition over soil and subsoil: Land Grabbing by Local Elites in Eastern DRC (Kalehe, South Kivu)."

[30] Huggins, C. (2021). Overlaps, Overestimates and Oversights: Understanding Domestic and Foreign Factors in the Land Rush in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Transnational Land Rush in Africa: A Decade After the Spike. L. Cochrane and N. Andrews. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 235-260.

[31] Overbeek and Tamas (2018, 3) in Huggins (2021, 238)

[32] Bayengeha, F. (2014). Harnessing political will to induce land reform: The story of the Democratic Republic of Congo land reform. presentation at the 2014 World Bank Conference On Land And Poverty, Washington DC, The World Bank, March.

[33] Huggins, C. (2021). Overlaps, Overestimates and Oversights: Understanding Domestic and Foreign Factors in the Land Rush in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Transnational Land Rush in Africa: A Decade After the Spike. L. Cochrane and N. Andrews. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 235-260.

[34] Betge, D. (2019). Making land rights work: ZOA land rights guidelines. The Netherlands, ZOA.

[35] Molinario, G., M. Hansen, P. Potapov, A. Tyukavina and S. Stehman (2020). "Contextualizing landscape-scale forest cover loss in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) between 2000 and 2015." Land 9(1): 23.

[36] Tongele, T. N. (2021). "Human Ways of Life and Environmental Sustainability: Congo Basin Case Study." Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture 15: 547-559.

[37] International Crisis Group (2020). Mineral Concessions: Avoiding Conflict in DR Congo’s Mining Heartland. Africa Report N°290.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Molinario, G., M. Hansen, P. Potapov, A. Tyukavina and S. Stehman (2020). "Contextualizing landscape-scale forest cover loss in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) between 2000 and 2015." Land 9(1): 23.

[40] Behrendt, H., C. Megevand and K. Sander (2013). "Deforestation Trends in the Congo Basin."

[41] https://unfccc.int/topics/land-use/workstreams/redd/what-is-redd

[42] Fairhead, J., M. Leach and I. Scoones (2012). "Green grabbing: a new appropriation of nature?" Journal of peasant studies 39(2): 237-261.

[43] Huggins, C. (2021). Overlaps, Overestimates and Oversights: Understanding Domestic and Foreign Factors in the Land Rush in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Transnational Land Rush in Africa, Springer: 235-260.

[44] Huggins, C. (2021). Overlaps, Overestimates and Oversights: Understanding Domestic and Foreign Factors in the Land Rush in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Transnational Land Rush in Africa: A Decade After the Spike. L. Cochrane and N. Andrews. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 235-260.

[45] Lawson, S. (2014). "Illegal logging in the Democratic Republic of the Congo." Energy, Environment and Resources EER: 2014.

[46] Rainforest Foundation UK. (2019). "Donors called on to address breakdown in forest governance in Dr Congo as Chinese company accused of widespread illegal logging." Retrieved 8 March 2021, from https://www.rainforestfoundationuk.org/global-donors-called-to-address-forest-governance-breakdown-in-dr-congo-as-chinese-company-accused-of-widespread-illegal-logging.

[47] RIAO-RDC. (2019). "Violent tensions at Feronia's oil palm plantations in the DR Congo." Retrieved 30 May 2022, from https://grain.org/en/article/6182-violent-tensions-at-feronia-s-oil-palm-plantations-in-the-dr-congo.

[48] Huggins, C. (2021). Overlaps, Overestimates and Oversights: Understanding Domestic and Foreign Factors in the Land Rush in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Transnational Land Rush in Africa: A Decade After the Spike. L. Cochrane and N. Andrews. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 235-260.

[49] Global Witness (2009). "Faced with a gun what can you do?" War and the militarisation of mining in eastern Congo. London, Global Witness.

[50] Huggins, C. (2021). Overlaps, Overestimates and Oversights: Understanding Domestic and Foreign Factors in the Land Rush in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Transnational Land Rush in Africa: A Decade After the Spike. L. Cochrane and N. Andrews. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 235-260.

[51] Kelly, A. (2019). "Apple and Google named in US lawsuit over Congolese child cobalt mining deaths." Retrieved 6 March, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/dec/16/apple-and-google-named-in-us-lawsuit-over-congolese-child-cobalt-mining-deaths.

[52] UN Security Council (2001). Report of the Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of DR Congo.

United Nations, Global Witness (2009). Faced with a gun what can you do? War and the militarisation of mining in eastern Congo. London.

Global Witness, Pole Institute (2010). Blood Minerals: The Criminalization of the Mining Industry in Eastern DRC. Goma, Institut Interculturel dans la Région des Grands Lacs.

Callaway, A. (2018). Powering down corruption. The Enough Project: 1-28.

Baraza, S. (2020). DRC: A history of pillage, destination unknown. The Africa Report 2021.

Padalecki, I. G. (2020). Cobalt, Computation, and the Congo:Making Corporations Pay for Their Transnational Terrors. Inquiries 12(9).

Responsible Mining Foundation (2021). Time to normalise respect and remedy for Human Rights in mining. Research Insight.

[53] Callaway, A. (2018). Powering down corruption. The Enough Project: 1-28.

[54] Mousseau, F. (2019). The Bukanga Lonzo Debacle: The failure of agro-industrial parks in the DRC. Oakland California, The Oakland Institute.

[55] Mudinga, E. M. and C. I. Wakenge (2021). Land Crisis and Stakeholders’ Responses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Congo Research Briefs Issue 9, SSRC, Governance in Conflict Network, GEC-SH, CRG and CRP.

[56] Ibid. P.5.

[57] De Boeck, F. (2015). "“Poverty” and the politics of syncopation: urban examples from Kinshasa (DR Congo)." Current Anthropology 56(S11): S146-S158.

[58] World Bank (2018). Democratic Republic of the Congo: Urbanisation review. Washington DC.

[59] Büscher, K. (2018). "African cities and violent conflict: the urban dimension of conflict and post conflict dynamics in Central and Eastern Africa." Journal of Eastern African Studies 12(2): 193-210.

[60] Hothschild, A. (1998). "King Leopold’s ghost." New York: McMillan.

[61] Huggins, C. (2021). Overlaps, Overestimates and Oversights: Understanding Domestic and Foreign Factors in the Land Rush in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Transnational Land Rush in Africa: A Decade After the Spike. L. Cochrane and N. Andrews. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 235-260.

[62] Betge, D. (2019). Making land rights work: ZOA land rights guidelines. The Netherlands, ZOA.

[63] Bisoka, A. N. and K. Claessens (2019). "Real Land Governance and the State: Local Pathways of Securing Land Tenure in Eastern DRC." Negotiating Public Services in the Congo State, Society and Governance: 190-213.

[64] Trefon, T. (2016). Congo's Environmental Paradox: potential and predation in a land of plenty, Zed Books Ltd.

Authored on

28 June 2022