Updated on 21 December 2023

Estimates vary widely as to the number of pastoralists globally. These variations reflect different definitions. Using a broad definition where pastoralists are defined as people who generate more than 50% of their income from extensive livestock production in which mobility is a key management tool, there are around 500 million pastoralists worldwide.1 Other estimates which are premised on narrower definitions estimate there are in excess of 200 million pastoralists worldwide. Of these some 45% are in Asia, 37% in Africa and 18% in Latin America2 . Africa is the continent that has the largest land area allocated to pastoral land use—about 40% of land mass—and the largest percentage of the population dedicated to pastoralism.3 In sub-Saharan Africa alone, over 120 million people obtain their livelihood from livestock production of whom 41 million depend solely on livestock for their livelihoods.4 The world map of pastoralists which has been prepared for the 2026 International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists currently has information on over 800 groups of pastoralists worldwide.5

Pastoralists herd and manage around 1 billion animals worldwide, including sheep, goats, cattle, camels, yaks, horses and reindeer.6 Rangelands consist of seven biomes which cover 54% of the terrestrial surface of the globe.7. The largest rangeland biome is deserts and xeric shrubland which covers 19% of the global terrestrial surface.8 These are the Rangeland biomes Percentage breakdown between rangeland biomes; Deserts and xeric shrubland 35% Tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas and shrub lands 26% Tundra 15% Temperate grasslands, savannas and shrub lands 13% Montane grasslands and shrub lands 6% Mediterranean forests 4% Flooded grasslands and savannas 1% Together these rangelands harbour an estimated 35% of global biodiversity hotspots and provide habitat for 28% of endangered species.9 They also store some 30% of terrestrial carbon. Grazing lands sequester between 200-500kg of carbon per hectare per year, playing a leading role in climate change mitigation.10 Recent research suggests that as a consequence of climate change, in certain circumstances grasslands may become a more reliable carbon sink than forests.11

Faits marquants: Rangelands, Drylands & Pastoralismparcourir tout

Key concepts and terms

It is important to distinguish between rangelands and drylands. These often overlap, but they are not the same thing. Not all drylands are rangelands, and while all drylands are found within rangeland areas12 , some dryland regions may have different ecosystems which do not support grazing activities.

Rangelands

Rangelands are specific types of landscapes dominated by various types of vegetation, including grasses, shrubs, and forbs. These areas are used for grazing livestock and wildlife, rather than for intensive agriculture. This vegetation is typically natural or semi-natural or untransformed. This is the source of its biodiversity value which enables wildlife and other biodiversity to coexist with pastoralism. Overall, 78% of rangelands (approximately 62,000,000 km2) are classified as drylands.13

Globally, rangelands comprise the largest land use, estimated to cover about 25% of Earth's land surface.14 This makes them an essential resource for both maintaining environmental services like biodiversity conservation, carbon sequestration and as a source of livelihood, especially for rural communities. Rangelands are used primarily as a source of feed for livestock. They also provide important secondary resources such as firewood, wild foods, medicinal plants, and water.15

Drylands

Drylands are geographical areas characterized by a lack of sufficient water to support forest – whereas they can support grassland, shrubland and savanna. They have low annual precipitation and often experience high evaporation rates, which makes it challenging for plants to grow. Drylands are distributed among all continents and cover about 41 percent of the Earth’s land surface, totalling more than 6 billion hectares in extent.16 They support 2 billion people, about 90 percent of them in developing countries. Dryland ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to water shortage, drought, desertification, land-use change and degradation and climate change impacts. These vulnerabilities impact on the food security, livelihoods and wellbeing of their populations.17

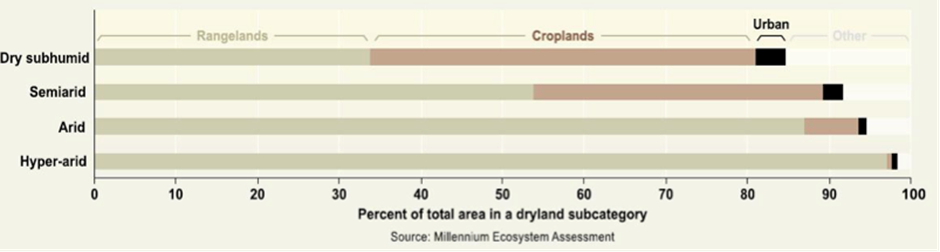

Drylands can be classified into four categories based on precipitation: dry sub-humid, semi-arid, arid and hyper-arid.

Distinguishing dryland systems. Source: Millenium Ecosystem Assessment

Within these four subtypes, land use is significantly influenced by rainfall, with crop production declining rapidly with increasing aridity.

Dryland sub categories

Pastoralism

Pastoralism is a livelihood system in which people rely primarily on the domestication and herding of animals for their livelihoods. Pastoralists depend on animals such as cattle, sheep, goats, camels, yaks, reindeer, or other herd animals for food, clothing, and various other products. Pastoralists are nomadic or semi-nomadic, moving their herds from one grazing area to another in search of fresh pasture and water sources. Pastoralists have an intricate understanding of the relationship between seasonality and changes in the availability of forage and water to support stock. But pastoral livelihoods have been undergoing major changes with policy makers often encouraging them to become more settled. Settlement incentives have been provided by drilling to exploit groundwater resources which has encouraged year-round grazing. This has had unintended consequences within rangeland ecologies, changing the species composition and resulting in the effective grazing out of highly palatable species.18 Now as the impacts of climate change affect the availability of grazing and the reliability of water sources, herders must migrate even longer distances with their herds. Competition for grazing and water resources has increased. This also reflects the concentration of livestock ownership in the hands of elites and the emergence of militarised ‘neo-pastoralist models that provide trigger points for armed conflict.19

Nomadism

Nomads do not live continually in the same place but move between places seasonally. Some nomads are hunter gatherers, but the majority are pastoral nomads, who may also act as traders.

Transhumance

There are two forms of transhumance: vertical and horizontal.20 Vertical transhumance sees herders move with their livestock between mountain pastures in warm seasons, and lower altitudes during the rest of the year. Horizontal transhumance occurs in widely different settings ranging from Siberia where herders move with their reindeer between the subarctic taiga and the Arctic tundra to East Africa where herders move determined by rainfall seasonality. Most peoples who practice transhumance also engage in some form of summer crop cultivation, and usually occupy some kind of permanent settlement.21

Degradation

The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes that land degradation is defined in many different ways within the literature, with differing emphases on biodiversity, ecosystem functions and ecosystem services. The IPCC defines land degradation as “a negative trend in land condition, caused by direct or indirect human-induced processes including anthropogenic climate change, expressed as long-term reduction or loss of at least one of the following: biological productivity, ecological integrity or value to humans”.22

Land degradation neutrality

The concept of LDN emerged from the UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) in 2012 focusing on how to intensify the production of food, fuel and fibre to meet future demand without further degrading our finite land resource base. LDN envisions a world where human activity has a neutral, or even positive, impact on the land.23

There is a global commitment to working to halt and reverse land degradation, restore degraded ecosystems and sustainably manage resources through a commitment to land degradation neutrality (LDN). While there is agreement that this is necessary, views and approaches vary widely on how best to achieve LDN. Currently, the global cost of land degradation reaches about US$490 billion per year, much higher than the cost of action to prevent it.24

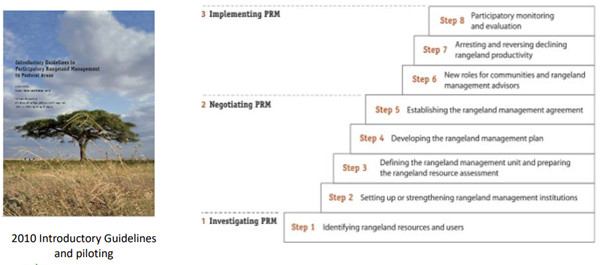

Participatory rangeland management

Rangeland users and communities play a central role in Participatory Rangeland Management (PRM) planning and monitoring processes, which can be supported by government departments, NGOs and rangeland scientists. Many PRM agreements remain oral and undocumented. However, some consultative processes result in a participatory rangeland management agreement which is both legally binding and can be effectively monitored.25

International legal framework and policies

Pastoralists are increasingly vulnerable to a wide range of threats. These include competition for resources which have intensified due to climate change; land grabs and security threats, particularly where pastoral ecosystems extend beyond national boundaries.26

There are a range of international laws already in force which provide some basis for protecting the rights of pastoralist peoples. These include international law relating to human rights, indigenous peoples, minority rights, and the right to development. However, it has been proposed that a specific category of rights should expressly to pastoralist peoples, so as to make these rights more effective.27 This is a complex task as pastoralists operate under widely differing ecological and political circumstances.

To date, much of the work in the international policy and legal sphere has been conducted by the FAO. This has sought to counter widespread prejudice against pastoralists who in many instances have been considered “backwards looking and unproductive and have historically been undermined by adverse legislation and a lack of supportive legislation.” 28

In 2016, FAO launched a technical guide on Improving governance of pastoral lands.29 This was to support implementation of the 2012 Voluntary guidelines on the governance of responsible tenure of land, fisheries and forests in the context of national food security.30

A 2018 review of legal and policy arrangements for cross-border pastoral mobility31 sought to assist governments and civil society actors in developing legislation and cooperative agreements to facilitate transboundary pastoralism.

A recent FAO handbook32 further advocates the right to livelihood for pastoralists and makes the argument that that securing pastoral mobility is central both to the practice of pastoralism and environmental sustainability in the rangelands. However, as early as 2010 The African Union (AU) published a policy framework for pastoralism in Africa.33 Framework principles include recognition of:

- the rights of pastoralists;

- pastoralism as a way of life and a production system;

- the importance of strategic mobility;

- the importance of regional approaches to policy development and implementation.

Member states are responsible for adapting and adopting this framework at the national level. This includes a focus on supporting and promoting sustainable development in pastoral areas and providing support for policy development and harmonization.34 However, there has been limited uptake in this regard with the exception of the work of the AU- Inter-African Bureau for Animal Resources (AU-IBAR). This was founded in 1951 to fight rinderpest in Africa and retains a broad but non-legally binding mandate covering all aspects of animal resources, including livestock, pastoral livelihoods, fisheries and wildlife, across the entire African continent.

Mapping challenges and risks

Challenges and risks to pastoral systems and livelihoods vary widely and are highly context specific. On the African continent it has been reported that conflicts between pastoralists and settled communities have intensified.35 Disputes over land and water rights are common among pastoralists' groups and also between pastoralists and sedentary cultivators. In the absence of recognised land rights, pastoralists' grazing areas are also often considered as vacant land available to be sold or leased to private investors.36

As more pastoralists are encouraged to adopt more sedentary lifestyles37,communal rangelands in pastoral areas have been informally privatized. This is a source of conflict over key resources and fuels boundary disputes.38

Conflict has also been exacerbated by a variety of factors. These include:

- climate change, which drives herdsmen into expanded ranges in search of fodder and water;

- the multiplication of migration routes which cross transnational routes – a factor frequently interpreted as a security threat, particularly where relationships between neighbouring states have a history of conflict as in the Sahel

- the simultaneous expansion of cultivated areas and an increase in livestock herds, which have deepened the competition for water and access to grazing land.39

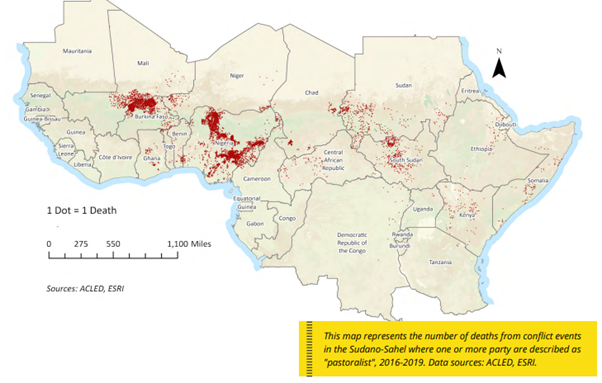

In Africa many conflicts related to pastoralism centre in the Sudano-Sahel ecological zone,40 but in the last decade these have extended further south to the DRC, Uganda and Kenya.

Deaths relating to pastoral conflict 2016-2020 based on ACLED ESRI data41

It has been argued that conflict prevention requires governments to promote the regulation of transhumance in ways that include all relevant actors.42 However this remains unlikely in political contexts characterised by instability, where authoritarian states face insurgencies and where cross-border trafficking of people, weapons and resources is of mounting concern.43

For example, conflict in the Central African Republic (CAR) has been linked to “the migration of militarized pastoralist groups from surrounding countries into the southwest, long occupied by sedentary peoples engaged in farming, forest product extraction, and artisanal mining of rich alluvial diamond and gold deposits. Pastoralist herds owned by urban elites of the surrounding countries are attracted to the rich water and pasture resources of the southwest, but also, the gold and diamond deposits, a major source of income from illicit mining.”44

The CAR example shows how pastoral migration can become overlaid and complicated by other factors. Further, the resurgence of ‘fortress conservation’ in response to global commitments to expand protected areas, supposedly as a buffer to climate change, also impacts on land rights and the livelihoods of pastoralists.

In Tanzania where conservation areas comprise almost 30 per cent of the country’s land, an estimated 150,000 Maasai pastoralists are threatened with displacement by the establishment of new conservation initiatives in two areas in Ngorongoro district.45

Further south in Botswana, it has been observed how the impacts of land tenure policies have led to the expansion of both commercial agricultural activities and conservation areas. In this context policy makers consider communal rights “as a constraint that hinders development with a need to be modernised.”46 Uncertainties facing pastoralists are not restricted to sub-Saharan Africa. In South Asia pastoral groups in India, Pakistan, Nepal and Bhutan are reported to be “experiencing profound transitions due to social, political, ecological and climatic factors... These drivers result in winners and losers, as some pastoralists successfully adapt to new opportunities and pressures, while others are pushed out of pastoralism.”47

Uncertainties and environmental impacts have been amplified by the imposition of approaches to rangeland management developed in temperate areas. These have proved to be highly inappropriate for ecological settings where uncertainty and sharp season variations are the norm.48

This combination of factors raises questions about the future sustainability of pastoralism as a production and livelihood system. This highlights the need for continuing context specific research to inform policy choices.

"Policies and development programmes for pastoralists and their environments need to be founded on up-to-date, factual and objective information about what is happening, why and where it is happening and on the impacts.49"

Overall fresh thinking proposes that pastoral policies require major reframing in ways that actively link pastoralism, uncertainty, and development.

"This means a shift from a commitment to ‘control’ – and prediction, stability, and planning – to one that is centred on social relationships and institutions that support flexible and adaptive responses to the inevitable uncertainties of today’s world.50"

Community, customary and indigenous land rights

The land rights of pastoralists and those who access land through systems of customary tenure are frequently vulnerable to elite capture in the form of informal privatisation, enclosure and resource grabbing.

The Voluntary Guidelines (FAO, 2012) sought to protect and enhance the rights of pastoralist populations to lands long used for social, cultural, spiritual, and economic purposes. Part 3 of guidelines sets out principles to secure “legal recognition and allocation of tenure rights and duties, so as to protect the rights of indigenous peoples and other communities with customary tenure.”

Clause 9.5 states that “Where indigenous peoples and other communities with customary tenure systems have legitimate tenure rights to the ancestral lands on which they live, states should recognize and protect these rights. Indigenous peoples and other communities with customary tenure systems should not be forcibly evicted from such ancestral lands.”

However, on the 10th anniversary of the adoption of the VGGT it was recognised that there remained an urgent need to scale up implementation.

Recent FAO reports confirm that the land and resource rights of pastoralists often remain poorly understood and undervalued.51 Development initiatives which change land use, may fail to recognise the impacts on pastoral livelihoods, or compensate pastoralists for loss of grazing access.

Climate change

Anthropogenic pressures driving climate change and global warming, have led to the deterioration of the ecosystems on which pastoralists depend. Currently climate change impacts are being felt most acutely in Asia where the majority of the world’s pastoralists reside. Asia is currently warming faster than the global average. In 2022 a total of 81 weather, climate and water related disasters impacted on the lives of 50 million people.52 At the same time as parts of China have experienced prolonged droughts, severe flooding hit Pakistan.

A large portion of the Sahel is inhabited by pastoralists who engage in livestock herding, and this livelihood is very climate sensitive. In 2011 and 2017 droughts in the Horn of Africa resulted in massive cross-border displacement to Kenya, particularly from Somalia. “Drought-related displacement of pastoralists (not to be confused with the regular transhumance patterns) have led to conflicts over land and water resources among pastoralists and between pastoralists and settled farmers.”53

The Lake Victoria Basin (LVB) is one of the most mobile regions in the world, with a long history of trade, nomadic pastoralism, and dry season migration for livelihood diversification54 Nomadic pastoralists in the basin depend on favourable climatic conditions to access grazing and water resources. Here again severe droughts have aggravated recurring tensions between farmers and pastoralists. The high levels of temporary and circular migration in Rwanda, conflicts between pastoralists and farmers in Tanzania, and climate pressures forcing the Karamoja pastoralists in Uganda to migrate longer and farther away, are all identified as threats to regional stability.55

As global institutions examine causes and responses to the mounting climate crisis, there has been a tendency to oversimplify the role of livestock production and animal products as key drivers of climate change. Recent research argues that simplistic and homogenising narratives about livestock and animal products and the failure to differentiate livestock systems can be “misleading and dangerous.” 56 Such narratives have seen relatively low impact, extensive livestock production, such as pastoral systems “being lumped in with industrial systems in the conversation about the future of food”.57

Another major climate-change related threat to rangelands is the pressure to use rangeland areas for nature-based solutions such as afforestation and other schemes which often target “empty” or “unused” land. Outdated theories on desertification and afforestation that widely shaped colonial policy and practice continue to influence science-policy frameworks. 58 This has led to “large areas of savanna being misclassified as degraded forests and targeted by inappropriate restoration and fire suppression policies”.59 Simultaneously, the rise of massive carbon offsetting projects, which have come under increasingly critical scrutiny, has seen the rights to huge tracts of land in multiple African countries being sold off in deals which will span decades.60

Recent studies present evidence which shows that in contrast to intensive livestock systems, extensive and mobile livestock production can be climate neutral, or even climate positive.61 Mobile pastoral practices that distribute livestock manure/urine and incorporate it, add to carbon cycling. There is a strong evidence base which shows that pastoral systems do not automatically cause ‘desertification’, as is sometimes assumed; but can enhance biodiversity and offer a low-carbon alternative to industrialised systems.62 Overall ecological management systems associated with pastoralism may far exceed the benefits of ‘protecting’ these ecosystems through exclusionary conservation.63

Women and youth in pastoralist societies

The role and place of women in pastoralist societies has been the subject of in-depth research.64 This emphasises that while there are millions of pastoral households worldwide, their social and familial contexts vary enormously. This in turn shapes the spaces that women occupy within them. These differences require critical assessment of generalised and dominant narratives which tend to foreground the marginalisation and oppression of women within pastoralist households, in favour of understandings of the role and place of women which are more solidly grounded in pastoralist life worlds and cultural norms.65

A recent review indicates that women in pastoral societies are involved in a wide range of economic and livelihood activities. These include “direct livestock production like cattle herding and indirect complementary livestock activities like milking, processing, and sale of dairy products (cheese, butter, and milk), crop farming, petty trading, skin/leather works, extracting rangeland products like firewood, and charcoal, among others.”66

It has been observed that when it comes to climate change, women and girls bear the greatest burden of drought, as they must continue to perform their reproductive and productive roles, while being forced to contribute more to household adaptation with less. 67

The position of pastoral youth is more complex. There are persistent narratives that young people in these societies are no longer interested in pastoral livelihoods. However, a recent FAO study draws attention to structural changes which have “transformed the pathways to autonomy open to young people, who now find themselves in family economies that are no longer uniquely pastoral”.68 This observes how “the pathways to adult status in pastoral societies are undergoing major transformations …that are reconfiguring the organization of the family.”69

Land governance innovations and empowerment in pastoralist settings

Much of the impetus for innovation and empowerment has stemmed from programmes for participatory rangeland management (PRM).

PRM supports community leadership and inclusiveness in land use planning policy and practice. It takes into account the interests, positions and needs of all rangeland users in pastoral areas and offers opportunities for negotiations to be carried out between these different stakeholders to come to agreement over the future of pastoral land use.70

While presented as a linear process of steps in the graphic below, in practice the process involves iteration between steps and integrates cross-cutting activities, including conflict resolution and institutional capacity development.

The outcome envisages that the agreed upon customary institution(s) and/or defined community rangeland management group are legally enabled to oversee the sustainable management of the natural resources in a specific rangeland area. PRM also enables the increased participation of women. A recent evaluation of PRM processes in Tanzania and Kenya confirms that many of the envisaged benefits of PRM are materialising, including the improvements in the condition of the rangeland.

Reframing pastoral policies: A Kenyan case study

In the Olgos area of Narok county in Kenya there has been an important community initiative to re-commonise Maasai rangelands. This has particular relevance as it runs counter to state policies and practices which have sought to settle pastoral communities and impose inappropriate livestock and rangeland management models.

In Kenya Maasai rangelands had been fragmented and fenced off as a result of a national government initiative dating back to the 1970s. These sought to subdivide commonly held lands and promote market orientated livestock keeping in Maasai pastoralist areas. This envisaged the individualisation of tenure in terms of the Land Registration Act of 1968 and the Land Adjudication Act of 1970.

This approach had disastrous consequences. “Within five years of the subdivision and fencing off, the area has undergone more extensive modification and degradation than at any other time in history.”71 The livestock population fell by about 60% and wild animals, especially large game, were moved to other areas. The erection of fences and the fragmentation of the land became drivers of local conflict and disputes over access to water and other resources. The erosion of community norms and values precipitated a local community intervention to find solutions.

A series of consultative meetings presided over by the most senior Maasai leaders identified a range of common challenges which needed urgent action. These included:

- the breakdown of social networks and cohesion;

- mounting human wildlife conflicts;

- shrinking herd sizes and related food insecurity;

- ecological degradation resulting from enclosure and insufficient access to land.

The community meetings resolved that all the fencing should come down and the land held by the community should revert to a Commons which should be accessible to all. Contrary to the outcomes forecast by the tragedy of the commons narrative72, these measures combined a 40% increase in family herds, the return of wild animals and environmental regeneration – all leading to improved social cohesion over time.73

Ways forward

Policy and development practice are often infused with anti-pastoralist bias which assumes that the way forward lies in “transforming the pastoralists to become something else”74. To the contrary research indicates that the assumptions many policy makers have about pastoralists are misplaced.

Rather we need to recognise that:

- As climate change and other forms of uncertainty intensify, pastoralists have unique knowledge and skills to respond flexibly and effectively

- Mobility is central to pastoral practices and a key part of pastoralists' responses to variability.

- Extensive livestock systems can enhance biodiversity and these practices can far exceed the benefits of ‘protecting’ these ecosystems through exclusionary conservation.

- In contrast to intensive systems, extensive and mobile livestock production can be climate neutral or even climate positive.75

Authorship

This issue page has been researched and written by Rick de Satgé. Peer review was provided by Susanne Vetter, Associate Professor, Department of Botany, Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa.

References

[1] Flintan, F. (2019). PIM Webinar: Innovations to help secure pastoral land tenure and governance. Research Program on Policies, Institutions and Markets led by IFPRI, CGIAR.

[2] USAID (2013). Pastoral Land Rights and Resource Governance. R. Behnke and M. Freudenberger. Washington DC, United States Agency for International Development.

[3] Ibid.

[4] De Haan, C., E. Dubern, B. Garancher and C. Quintero (2016). Pastoralism development in the Sahel: A road to stability. Fragility, Conflict, and Violence Cross-Cutting Solutions Area. Washington DC, World Bank.

[5] Mundy, P. (2023). "World map of pastoralists." Retrieved 27 July, 2023, from http://www.pastoralpeoples.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Pastoralist-map-poster-7.23-print.pdf.

[6] FAO. (2023). "Pastoralist Knowledge Hub: Key facts." Retrieved 24 July, 2023, from https://www.fao.org/pastoralist-knowledge-hub/en/.

[7] ILRI, I., FAO, WWF, UNEP and ILC, (2021). Rangelands Atlas Nairobi, Kenya International Livestock Research Initiative (ILRI).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Niamir-Fuller, M. (2022). "Sustainable pastoralism: a Nature-based Solution proven over millennia." Crossroads Blog https://www.iucn.org/crossroads-blog/202206/sustainable-pastoralism-nature-based-solution-proven-over-millennia 2023.

[10] FAO. (2023). "Pastoralist Knowledge Hub: Key facts." Retrieved 24 July, 2023, from https://www.fao.org/pastoralist-knowledge-hub/en/.

[11] Dass, P., B. Z. Houlton, Y. Wang and D. Warlind (2018). "Grasslands may be more reliable carbon sinks than forests in California." Environmental Research Letters 13(7): 074027.

[12] ILRI, I., FAO, WWF, UNEP and ILC, (2021). Rangelands Atlas Nairobi, Kenya International Livestock Research Initiative (ILRI).

[13] Ibid.

[14] UNEP. (2021). "New atlas reveals rangelands cover half the world’s land surface, yet often ignored despite threats." Retrieved 25 July, 2023, from https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/new-atlas-reveals-rangelands-cover-half-worlds-land-surface-yet.

[15] Seware, B. (2015). "Rangeland degradation and restoration: A global perspective." Point Journal of Agriculture and Biotechnology Research 1(2).

[16] ILRI, I., FAO, WWF, UNEP and ILC, (2021). Rangelands Atlas Nairobi, Kenya International Livestock Research Initiative (ILRI).

[17] FAO. (2019). "Trees, forests and land use in drylands: the first global assessment – Full report." FAO Forestry Paper No. 184. Rome. Retrieved 25 July, 2023, from https://www.fao.org/3/ca7148en/ca7148en.pdf.

[18] Flintan, F. and A. Cullis (2010). Introductory Guidelines to Participatory Rangeland Management in Pastoral Areas, Save the Children USA Ethiopia Country Office, FAO Emergency and Rehabilitation Co-ordination Office and European Commission Directorate General for Humanitarian Aid (ECHO).

[19] Luizza, M. (2019). "Urban Elites’ Livestock Exacerbate Herder-Farmer Tensions in Africa’s Sudano-Sahel." New Security Beat: The blog of the environmental change and security program https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2019/06/urban-elites-livestock-exacerbate-herder-farmer-tensions-africas-sudano-sahel/ 2023.

[20] Mundy, P. (2023). "World map of pastoralists." Retrieved 27 July, 2023, from http://www.pastoralpeoples.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Pastoralist-map-poster-7.23-print.pdf.

[21] (2023). Transhumance. Encyclopedia Britannica.

[22] IPCC (2022). Chapter 4: Land degradation. Special report on climate change and land, International Panel on Climate Change.

[23] GEF. (2023). "Land degradation neutrality." Retrieved 27 July, 2023, from https://www.thegef.org/what-we-do/topics/land-degradation-neutrality#:~:text=The%20concept%20of%20LDN%20emerged%20from%20the%20UN,without%20further%20degrading%20our%20finite%20land%20resource%20base.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Flintan, F. and A. Cullis (2010). Introductory Guidelines to Participatory Rangeland Management in Pastoral Areas, Save the Children USA Ethiopia Country Office, FAO Emergency and Rehabilitation Co-ordination Office and European Commission Directorate General for Humanitarian Aid (ECHO).

[26] International Crisis Group (2014). The security challenges of pastoralism in Central Africa. Africa Report No 215.

[27] Lopez, M. (2016). "The Rights of Pastoralist Peoples. A Framework for their Recognition in International Law." The Age of Human Rights Journal: 83.

[28] FAO (2022). Making way: developing national legal and policy frameworks for pastoral mobility. FAO Animal Production and Health Guidelines 28. Rome, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

[29] FAO (2016). Improving governance of pastoral lands: Implementing the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security. Governance of Tenure . Technical Guide No. 6. Rome.

[30] FAO (2012) "Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security."

[31] FAO (2018). Crossing boundaries: Legal and policy arrangements for cross border pastoralism. Rome, FAO and IUCN.

[32] FAO (2022). Making way: developing national legal and policy frameworks for pastoral mobility. FAO Animal Production and Health Guidelines 28. Rome, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

[33] African Union (2010). Policy framework for Pastoralism in Africa: Securing, Protecting and Improving the Lives, Livelihoods and Rights of Pastoralist Communities. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

[34] Devex. (2023). "African Union InterAfrican Bureau for Animal Resources (AU-IBAR)." Retrieved 27 July, 2023, from https://www.devex.com/organizations/african-union-interafrican-bureau-for-animal-resources-au-ibar-124661.

[35] International Crisis Group (2014). The security challenges of pastoralism in Central Africa. Africa Report No 215.

[36] Capacity4dev. (2014). "Pastoralism and Conflict." Retrieved 27 July, 2023, from https://capacity4dev.europa.eu/articles/pastoralism-and-conflict.

[37] Tuffa, S. (2022). "Maintaining Sustainability and Resilience in Rangeland Ecosystems." Research in Ecology 4(2): 51-55.

[38] Korf, B., T. Hagmann and R. Emmenegger (2015). "Re-spacing African drylands: Territorialization, sedentarization and indigenous commodification in the Ethiopian pastoral frontier." The Journal of Peasant Studies 42(5): 881-901.

[39] International Crisis Group (2014). The security challenges of pastoralism in Central Africa. Africa Report No 215.

[40] De Haan, C., E. Dubern, B. Garancher and C. Quintero (2016). Pastoralism development in the Sahel: A road to stability. Fragility, Conflict, and Violence Cross-Cutting Solutions Area. Washington DC, World Bank.

[41] Jobbins, M., A. McDonnell and L. Brottem (2021). Pastoralism and Conflict: Tools for Prevention and Response In the Sudano-Sahel. 2nd Ed. Washington DC, Search for Common Ground.

[42] International Crisis Group (2014). The security challenges of pastoralism in Central Africa. Africa Report No 215.

[43] Jobbins, M., A. McDonnell and L. Brottem (2021). Pastoralism and Conflict: Tools for Prevention and Response In the Sudano-Sahel. 2nd Ed. Washington DC, Search for Common Ground.

[44] Freudenberger, M. and Z. Mobga (2018). The Capture of the Commons: Militarized Pastoralism and Struggles for Control of Surface and Sub-Surface Resources in Southwest Central African Republic. Land Governance in an Interconnected World: Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington, DC.

[45] Nyeko, O. and J. Nnoko-Mewanu. (2022). "Tanzania Should Halt Plan to Relocate Maasai Pastoralists." Retrieved 28 July, 2023, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/02/22/tanzania-should-halt-plan-relocate-maasai-pastoralists.

[46] Basupi, L. V., C. H. Quinn and A. J. Dougill (2017). "Pastoralism and Land Tenure Transformation in Sub-Saharan Africa: Conflicting Policies and Priorities in Ngamiland, Botswana." Land 6(4): 89.

[47] Kerven, C. and R. Singh (2022). "Special issue on Pastoralism in South Asia." Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice.

[48] Scoones, I., Ed. (2023). Pastoralism, Uncertainty and Development. Rugby, Warickshire, UK, Practical Action Publishing.

[49] Kerven, C. (2023). "Edito's quote." Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice.

[50] Scoones, I., Ed. (2023). Pastoralism, Uncertainty and Development. Rugby, Warickshire, UK, Practical Action Publishing. P.4

[51] FAO and IFAD (2022). Geotech4Tenure. Technical guide on combining geospatial technology and participatory methods for securing tenure rights. Rome, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

[52] Loughran, J. (2023). "Climate change ramping up faster in Asia than rest of the world." Retrieved 28 July, 2023, from https://eandt.theiet.org/content/articles/2023/07/climate-change-ramping-up-faster-in-asia-than-rest-of-the-world/.

[53] IOM (2018). Migration in Kenya: A Country Profile. Nairobi, Kenya, International Organization for Migration.

[54] Rigaud, K. K., A. de Sherbinin, B. Jones, S. Adamo, D. Maleki, A. Arora, F. Casals, T. Anna, T. Chai-Onn and B. Mills (2021). Groundswell Africa: Internal Climate Migration in the Lake Victoria Basin Countries. Washington, DC., World Bank,.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Scoones, I. (2022). Livestock, climate and the politics of resources: A primer. Amsterdam, The Transnational Institute.

[57] Houzer, E. and I. Scoones (2021). Are Livestock Always Bad for the Planet? Rethinking the Protein Transition and Climate Change Debate. Brighton, University of Sussex, Pastoralism, Uncertainty, Resilience: Lessons from the Margin Programme.

[58] Vetter, S. (2020). "With Power Comes Responsibility – A Rangelands Perspective on Forest Landscape Restoration." Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 4.

[59] Ibid. P.3

[60] van Niekerk, P. (2023). Dubai carbon trader buys up African forests — saving the planet or environmental colonialism? Daily Maverick. South Africa.

[61] Scoones, I. (2022). Livestock, climate and the politics of resources: A primer. Amsterdam, The Transnational Institute.

[62] PASTRES (2022). The benefits of pastoralism for biodiversity and the climate. Pastoralism and biodiversity: Brief 1/6. University of Sussex, Pastoralism, Uncertainty, Resilience: Global Lessons from the Margins Programme.

[63] Scoones, I. (2022). Livestock, climate and the politics of resources: A primer. Amsterdam, The Transnational Institute.

[64] Flintan, F. (2008). Women's empowerment in pastoral societies, World Institute for Sustainable Pastoralism (WISP), Global Environment Facility (GEF), UNDP and IUCN.

[65] Hodgson, D. L. (1995). The politics of gender, ethnicity and" development" images, interventions and the reconfiguration of Maasai identities in Tanzania, 1916-1993, University of Michigan, Hodgson, D. L. (2000). Gender, culture & the myth of the patriarchal pastoralist, Hodgson, D. L. (2017). Gender, justice, and the problem of culture: from customary law to human rights in Tanzania, Indiana University Press.

[66] Onyima, B. N. (2021). Women in Pastoral Societies in Africa. The Palgrave Handbook of African Women's Studies. O. Yacob-Haliso and T. Falola. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 2425-2446.

[67] SNV. (2020). "Women and pastoralism: taking action for equality: Interview with Mary Njuguna." Retrieved 29 July, 2023, from https://www.snv.org/update/women-and-pastoralism-taking-action-equality.

[68] FAO (2020). Pastoralist youth in towns and cities Supporting the economic and social integration of pastoralist youth: Chad and Burkina Faso. Rome, Food and Agriculture Organisation. P.2

[69] Ibid. P. 15

[70] Flintan, F. and A. Cullis (2010). Introductory Guidelines to Participatory Rangeland Management in Pastoral Areas, Save the Children USA Ethiopia Country Office, FAO Emergency and Rehabilitation Co-ordination Office and European Commission Directorate General for Humanitarian Aid (ECHO).

[71] Tiampati, M. (2019). Recommonisation secures pastoralist production, livelihoods and ecosystem integrity in Olgos, Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya, AFSA, Pastoralist Development Network of Kenya.

[72] Hardin, G. (1968). "The tragedy of the commons." Science 168: 1243 - 1248.

[73] Tiampati, M. (2019). Recommonisation secures pastoralist production, livelihoods and ecosystem integrity in Olgos, Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya, AFSA, Pastoralist Development Network of Kenya.

[74] Mosebo, M. (2015). Livelihood of pastoral people is challenged by wrong assumptions, Danish Institute for International Studies.

[75] Scoones, I. (2022). Livestock, climate and the politics of resources: A primer. Amsterdam, The Transnational Institute.

Clause de non-responsabilité: Les données affichées sur le Land Portal sont fournies par des tiers indiqués comme source de données ou comme fournisseur de données. L'équipe du Land Portal s'efforce constamment de garantir le plus haut niveau possible de qualité et d'exactitude des données, mais ces informations sont par nature approximatives et peuvent contenir des inexactitudes. Les données peuvent contenir des erreurs introduites par le(s) fournisseur(s) de données et/ou par l'équipe du Land Portal. En outre, cette page vous permet de comparer des données provenant de différentes sources, mais tous les indicateurs ne sont pas nécessairement comparables statistiquement. La Fondation du Land Portal (A) décline expressément toute responsabilité quant à l'exactitude, l'adéquation ou l'exhaustivité de toute donnée et (B) ne peut être tenue pour responsable de toute erreur, omission ou autre défaut, retard ou interruption de ces données, ou de toute action entreprise sur la base de celles-ci. Ni la Fondation du Land Portal ni aucun de ses fournisseurs de données ne seront responsables de tout dommage lié à votre utilisation des données fournies ici.