By Yuliya Panfil, Omidyar Network

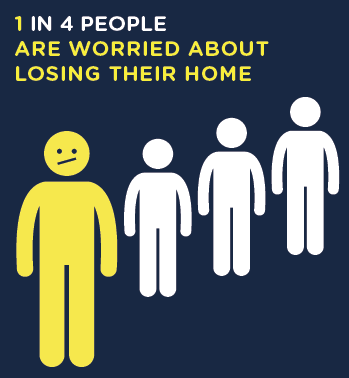

One in four people are worried about losing their home against their will in the next five years, according to a nine-country Gallup-led survey on people’s perceptions of their property rights. The survey, which polled 11,000 people across Peru, Colombia, Brazil, Greece, Indonesia, India, Egypt, Nigeria, and Tanzania, was released this week as part of the Global Property Rights Index (PRIndex) initiative.

PRIndex aims to measure — for the first time ever — people’s perceptions of the security of their land and property rights on a global level, with a goal of expanding to 140 countries over the next three years.

The PRIndex findings are important because they provide context for international donors who have spent billions of dollars to help people around the world map, document, and defend their property rights. They also may provide a crucial data source for the Sustainable Development Goals, which aim to measure as one of their indicators the proportion of the world’s adult population with secure rights to land.

The results shed light on a global crisis lurking in plain sight. If this data was to be extrapolated worldwide, these findings could potentially mean that two billion people around the world are scared that they’ll get booted from their homes or kicked off their land. And while a nine-country dataset is not robust enough to scientifically draw such a conclusion, even if it turned out to be half of that — one billion people — that’s still a big deal.

To many Americans, the problem of insecure property rights is foreign. Our land registries work well. Property documents are easy to get. And, barring extreme cases like eminent domain, we’re unlikely to be forced from our homes, assuming we’re paying our mortgage.

But that’s not the case in many places around the world. The World Bank estimates that only 30 percent of the world’s land rights are registered and recorded. In Africa, a measly 10 percent of rural land is registered. Even those with registered rights risk being kicked out of their homes due to corporate land grabs, land giveaways by corrupt governments, and ethnic conflict.

Without secure property rights, people have little incentive to invest in their home, or in their agricultural land if they are farmers. They don’t adopt productivity-boosting measures, don’t plant long-term crops, and don’t protect their property against the impacts of climate change. And forget about getting a bank loan without property documents.

Against this backdrop, it becomes critical to understand just how insecure people actually feel, why they feel insecure, and the impacts of their insecurity.

Here are the five things we found most interesting from the study and the three things we’re still wondering about.

Insecurity levels ranged from 10% in India to 31% in Nigeria. Unsurprisingly, renters were significantly more worried than homeowners that they would lose their homes — sometimes by a multiple of three.

A surprising amount, actually, if you look at the abysmal state of formal land registries in many developing countries and at the conventional wisdom that only a third of land rights across the world are registered and recorded. Nevertheless, self-reported documentation rates (including both formal and informal documents) ranged from 57% in Tanzania to 96% in Greece.

For example, in Colombia, 49% of those with property documents said they thought those documents would help protect their property, while 47% said they did not. In Indonesia, 42% of those without documents thought that having documents would help prevent property loss, while 52% didn’t think so.

One-sixth of those who had lived in their home for more than 10 years were worried about losing it. By contrast, 40% of those who had lived in their home for less than 5 years were worried. It seems that length of tenure is a more reliable predictor of security, than the presence of documents.

The proportion of residents who invested in major improvements to their homes in the last five years ranged from 34% in India to 64% in Brazil. In all cases, those who were secure in their property rights were also more likely to invest in improvements, though in some cases the difference was small, within the margin of error.

Some surprising results may be attributable to methodology and sampling quirks: PRIndex is still in its pilot phase, refining the way it’s selecting samples and asking questions. Other results have the power to debunk common misconceptions and change the way we think about property rights and land tenure security. Here are the three most surprising findings:

In many developing countries, only a small fraction of property is formally registered. So why are so many people saying they have property documents? At this point, we really don’t know. One hypothesis is that people possess documents that they believe evidence legal ownership, but that in fact do not (for example, utility bills, informal contracts, or maps showing the size of their plot). Another hypothesis is that respondents fibbed to pollsters for fear that they could get in trouble for living in a property without having documents.

A lot of people seemed to think that property documents were useless, at least when it came to helping them keep their property. It begs the question: what’s going on with the legal systems of these countries, that a title deed is not enough to keep you from being kicked out of your house? Another question is, what’s the point of giving people documents, if these documents won’t protect them, particularly in places where registering property is a long and expensive process?

Whereas a quarter of people said they were worried about losing their home, the percentage of people worried about losing property used to support the household (such as agricultural land) was much higher. For instance, in Tanzania and Indonesia, both highly agrarian societies, 41% and 38% of people, respectively, said they were worried about losing their land. Why do people feel less secure about the land they farm, than the land their house sits on? And what are the impacts of that difference?

As PRIndex continues piloting and testing its methodology, the answers to some of these questions may come into focus. Others will continue to befuddle experts. At the very least, PRIndex may yet launch a thousand PhD papers examining some of its more interesting results, sparking an evidence-based debate about how big the problem of property rights really is, and how we go about solving it.

A shorter version of this piece appeared on Place.

The Global Property Rights Index is an initiative of Omidyar Network and UK DfID, being implemented by Land Alliance in association with Gallup, Inc. To learn more, visit PRIndex.net.

Yuliya Panfil is an associate at philanthropic investment firm Omidyar Network, where she sources and manages investments for the firm’s Property Rights initiative. She was previously a land governance and legal advisor at USAID, where she oversaw USAID’s responsible land-based investment practice and led USAID’s private sector and donor engagement on land and property rights issues.

What We Learned

Roughly a quarter of those surveyed said they felt insecure in their property rights.

A lot of people said they have property documents.

But, many of them said they didn’t think their property documents would protect them.

In fact, the amount of time someone has lived in a place is a better predictor of their security than whether or not they possess documents.

Those with secure property rights are more likely to invest in upgrading their homes.

What We’re Scratching Our Heads About

Why did so many people say they have documents?

Why don’t people think that property documents will protect them?

Why are people more worried about losing their agricultural land, than losing their home?