Last week, I had the honour of moderating a panel on ‘Monitoring, Evidence and Data’ for Land Portal during the 10th Anniversary Event of the VGGT. The intention was to take inspiration from a recently published data story questioning the provision of data and monitoring to measure the impacts of the Voluntary Guidelines over the past 10 years. Yet the topic was already highly visible, garnering much attention during the first day of the event.

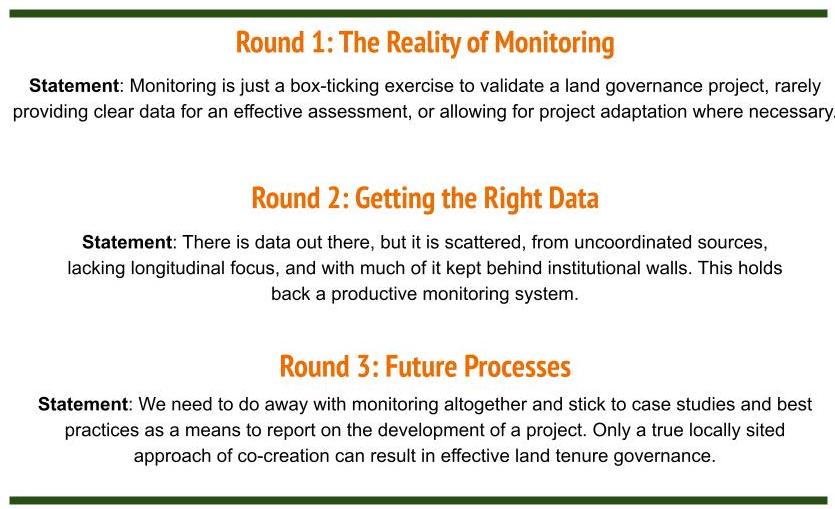

The session aimed to provoke discussion through responses to three contentious statements.

Guiding statements for the ‘Monitoring, Evidence and Data’ Session

The panel included seven of the sharpest minds in the land sector, representing large multi-lateral institutions such as the World Bank and implementors such as TMG, who support land degradation neutrality projects in several African countries. The discussion quickly moved to include voices both around the room on-site and in the online chat box. It is interesting to see how hybrid events can engage parallel simultaneous discussion.

Panellists from the ‘Monitoring, Evidence and Data’ Session

There are three key points of discussion I would like to highlight in this blog.

Firstly, we are not lacking for self-awareness about monitoring processes in land-relate development work. Yet this being the case, why is it that after 10 years of awareness-raising and implementation of the VGGTs, there remain significant deficiencies in its monitoring. Even if, as Francesco Maria Pierri of FAO points out, they do not have a mandate for such an activity concerning a non-binding set of guidelines. Mika-Petteri Torhonen from the World Bank asserted that there are robust and thorough programmes to monitor World Bank financed projects. However, he readily admitted that is not a perfect system and there is a need for greater flexibility and consultation as part of monitoring systems. On the other hand, Tony Piaskowy from Cadasta laid out the stark reality that many field projects operate under budgetary constraints, and so monitoring is at risk of becoming a tokenistic endeavour.

Secondly, while the basic notion of ‘open data’ seems irrefutable in its ability to support strong land policy, nevertheless it expands outwards into a complex and contested field. Harold Liversage from IFAD noted that ‘open’ does not necessarily equate with ‘accessible’. In this sense, Laura Meggiolaro from Land Portal is right to insist that open data is not an end unto itself. We need to ask questions as to whose data this is, who the data represents, and who it can impact upon.

There is a consensus of data contributing to the empowerment of community rights to land, and the use of open data to help them achieve secure tenure. Yet there is little sense of how this can be guaranteed, a fact that was highlighted in vital challenges from the floor. Angel Strapazzon from La Via Campesina emphasised the vital role that communities hold in the production of data, the place this data holds in filling knowledge gaps on land ownership and tenure security, and its ability to highlight shifts in this status. Yet Malcolm Childress from Global Land Alliance discerns that we are still only scratching the surface in terms of giving real voice to communities in the identification and preparation of projects, and then in the subsequent monitoring and evaluation as these projects proceed.

Thirdly, data is power and powerful actors may not wish to allow equitability in access and use. There are considerable risks in the participation of communities in data gathering and project monitoring. A culture of openness is fine but what if that data is then monopolised by other actors and used against the communities themselves. There are cases where data availability has resulted in land loss. As a result, we come to a stark contrasting reality, where Tony Piaskowy notes that Cadasta respects the rights of communities not to share data if they so wish. Francesco Maria Pierri promotes the value of multi-stakeholder platforms, many of which he sees as becoming more consolidated over time, playing an increased role in monitoring governance of tenure. Yet producing data over time can also become a burden to communities, and Frederike Klümper, from TMG, warns of data fatigue.

………………………………………………

The session covered considerable terrain, albeit without resulting in clear conclusions on how to improve data equity without putting communities at risk. From the point of view of Land Portal, it tapped into many existential discussions that we are already having. Namely, as we promote open data, what are the implications in terms of how this data is used, and with what consequences. It demands a real internal sharpening of the mind for us. In the meantime, it is vital that we keep up the conservation emerging from the issues raised in the session. It is a responsibility that Land Portal both acknowledges and accepts.