Over the past nine years, the project on Supporting Implementation of the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests (VGGT) has helped countries make political commitments towards the eradication of hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition, with the explicit outcome of increasing awareness among decision makers, development partners, and society at large regarding access to natural resources. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the Land Portal are holding two events to showcase the results achieved, learnings gained and key challenges to improving governance of tenure in different countries during the implementation project. In the context of these events, we spoke to Javier Molina Cruz, Senior Land Tenure Officer for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

What would you describe as a major contribution of the VGGT over the past ten years?

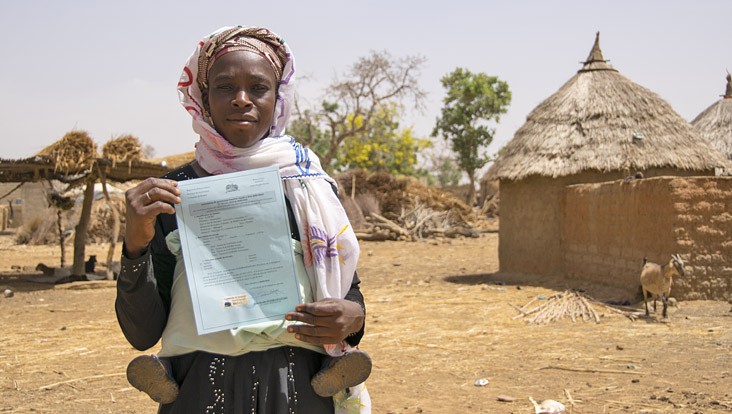

Sometimes the facts get overlooked in our desire to measure impact on policies, on the number of people and the number of countries who have benefited from changing land laws and policies. The Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security (VGGT) have been a game changer in terms of bringing marginalized groups into the policy debate for the first time ever. The VGGT have provided a framework for civil society organizations, farmers’ groups, and indigenous communities to contribute to policy discussions. Prior to the endorsement of the VGGT in 2012, engaging with these stakeholder groups was not on the agenda and was seen as an issue almost exclusively discussed by governments. The advent of the VGGT has been a significant change from the past.

And there's something additional that must be recognized. The current challenge has become policy implementation, which is not easy to overcome. Countries have adopted new land regulations and policies and yet they continue to struggle to implement these changes. In some cases, we have not seen much progress other than the mere adoption of these policies. The question now becomes: How can we engage different stakeholders in order to set in motion policy implementation? This is not an easy task, as we have to create momentum by building on the VGGT – which are a ‘soft law’ – while taking into account legislation that has been adopted over the past ten years in numerous countries.

We are now seeing emerging and pressing issues that we haven’t faced before, including changing weather patterns, land degradation, deforestation and the expansion of agricultural frontiers; this has become a problem for sustainability of systems and is leading to climate change like we have never seen before. The body of knowledge and our understanding of the impact of land use and its impact on climate change was not as fully understood in the past as it is today. Thirty years ago, very few people were talking about the linkages between land use and the need for a long term vision on use of natural resources; a concerted effort will be necessary to avoid these disconcerting trends.

We need to rethink the way we use land, how we use land to produce food and also how we relate to the environment to avoid biodiversity loss and the disruption of the equilibrium of ecosystems. We now have the tools to improve the governance of the way we use land and water. This critical moment will include not only governments, but community leaders, farmers’ groups, and private sector representatives. Moving forward, we will need to take it to the next level so that we can rise to the challenge of creating sustainable food systems worldwide.

What do you say to people who suggest the application of the VGGT is not moving fast enough?

We should keep in mind that when talking about access to and use of natural resources, we are often talking about private interests and vested interests. With power relationships and asymmetries at the country level, often those who advocate for more sustainable and more equitable access and use of land do not have the power to shift to a more equitable access and use of resources. Those who have vested interests in the status quo don't want to change because they're benefiting from the current standards. Obviously, their short term interests prevail over the long term interests of society as a whole.

Addressing these power asymmetries can be done through raising awareness of different stakeholders in society. Those vested interests are focusing on short term gain as opposed to the long term interests of society as a whole. We have to recognize that shifting these relationships is a long term endeavor. The current ownership structure wasn't built in a month or two, it has been built over centuries. We must take it step by step and with the VGGT the first step has been accomplished. Having a universal standard such as the VGGT translates to tenure rights that have been advocated for and understood by everybody. Similarly, we now have the ways and means to change policy, and over the years we have seen several concrete country case studies. We understand how people may be frustrated, as there are policies on paper that have yet to be translated into action, but I believe that in twenty or thirty years change can become a reality if we keep pushing for reform. We have always viewed tenure rights as a long term process and not something we can change or achieve overnight.

Can you describe some success stories of the VGGT?

We have seen numerous success stories in Colombia, for example how indigenous communities work with the national parks to administer territories that overlap; this land is recognized by the law as indigenous people’s territories, but at the same time they are national parks. A state agency has the mandate to manage this land, but there may be a diverse community living on or near those lands. There are also settlers who have no title or no claim to live in the national park, but who nonetheless live there. Through the VGGT, the indigenous communities and the agency are jointly managing the land. This large area of about 800 square kilometers has given the settlers a choice. They can either remain on the land, but they will have to abide by a certain code of conduct, meaning they cannot clear primary forest, they cannot pollute the lakes, lagoons, rivers and watersheds. They cannot hurt wildlife at will, but they must abide by hunting seasons, and if they infringe upon those regulations they must pay a fine. The National Park Agency supervises implementation, and communities themselves are also vigilant. The settlers are not allowed to sell or inherit the land. If they don’t agree to these terms, they must move out, and the lead agency then helps them find another place to live in the private market. This has helped stop illegal miners who were using arsenic and contaminating the watershed. This kind of experience does make a difference.

Another important example of changes being made comes from the international arena. The European Union, for instance, can drive change by encouraging consumers to only buy products showing the source country. There are certain criteria to enter the European Union Market, including prerequisites concerning the way food and commodities are procured and EU requirements can help encourage macro level changes. A concrete example is in Guatemala: When we first started engaging stakeholders in the 1980s to change land policy, there was an association of large landowners, including owners of large African palm oil plantations and banana plantations. We didn't get much of a reception, but after a process of talking to them and letting them know that if they don’t comply with certain standards, they may be excluded from selling their products on the global market. If they don't comply with the VGGT, we will communicate their non-compliance to the European Union and to the United States. After this, they started attending meetings. They started to be more open because they saw the writing on the wall, how things are changing. Change may come slowly, and in some places, more slowly than others. Yet over time, what FAO has introduced through the VGGT provides great value: access to governments and the legitimacy to reach out to all actors involved as a UN agency.