This profile by Rick de Satgé revises and updates the original profile which was prepared by the Advocates Coalition for Development and Environment in 2016. Open review was provided by Dr Brian Makabayi, a surveyor and lecturer in the Department of Geomatics and Land Management, School of the Built Environment, College of Engineering Design Art and Technology, Makerere University.

Uganda is a landlocked country located in East Africa with an area of 236,040 square kilometres and a total land boundary of 2,698 kilometres. It shares borders with South Sudan, Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

In Uganda, 76% of the population of 45 million people live in rural areas, and 73% of the workforce is employed in agriculture. Almost half of Uganda’s population is under the age of 15 and there are high levels of poverty (41%). Given that the majority of Ugandans depend almost exclusively on agriculture for their livelihood and food security, land remains a vital resource, making land governance a crucial political question.

A number of long-established, sophisticated and socially stratified African polities governed territories preceding the imposition of British colonial rule in 1894. The Bunyoro Kingdom in Western Uganda was historically the largest polity established in the 14th century.

Historical backdrop

Buhoma, Bwindi NP, Landscapes, Tropical Forest, Tropical Smallholdings, Uganda, Upland Farmland photo by Peter Steward,License CC BY-NC 2.0

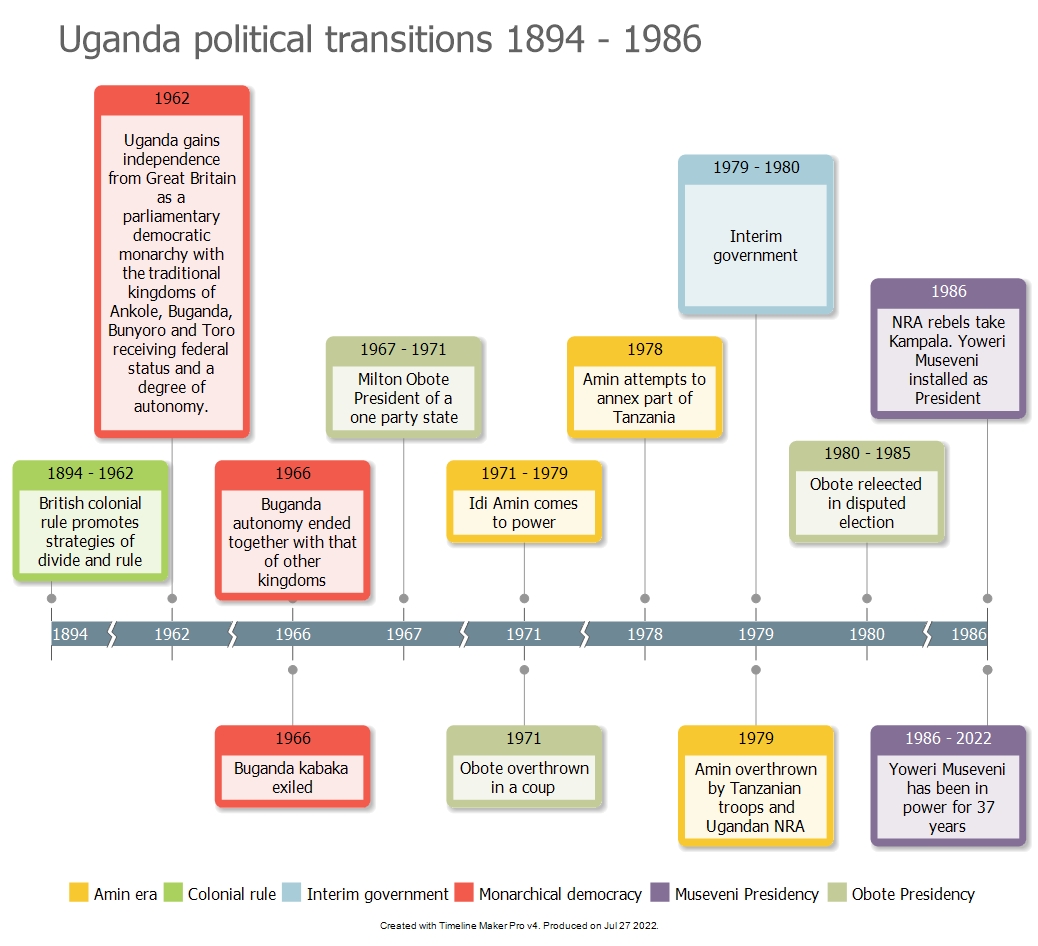

Uganda has a long history of conflict over land, water and pastures. These conflicts have been aggravated by changing political orders spanning the precolonial, colonial and post-colonial eras. The timeline below provides a high-level overview of the major political transitions in Uganda, from British colonial occupation, leading up to the installation of President Museveni in 1986.

A number of long-established, sophisticated and socially stratified African polities governed territories preceding the imposition of British colonial rule in 1894. The Bunyoro Kingdom in Western Uganda was historically the largest polity established in the 14th century1. However it had been eclipsed by the Buganda which dated back to the 12th century. At the time of colonial occupation Buganda was described as “a powerful, militarily organised feudal state”2.

British occupation was underpinned by the strategy of divide and rule3. This sought to keep kingdoms intact, consolidate and elevate ruling elites, while accentuating differences between the different polities and ethnic identities. Some, like the Bunyoro actively resisted British colonial control. In response, the British enrolled the support of the Buganda in their conflict with the Bunyoro. The British ceded two Bunyoro counties of Buyaga and Bugangaize to Buganda, once the Bunyoro leaders were defeated and exiled to the Seychelles.

Simultaneously, the British set out to co-opt the ruling elites within the Buganda state. The Buganda agreement of 1900 created a class of Buganda landlords which “would find it in its own interest to maintain the colonial status quo”4. This elite, which incorporated top social strata from the king down to local chiefs was allocated land as individual property. This had the effect of creating a hereditary ruling class5. The remainder of the land, much of it already directly occupied or claimed, was declared to be Crown land, administered by the Protectorate.

British colonial social engineering set the stage for land conflicts to come. Tenant grievances in the Buganda Kingdom were taken up by the Bataka Association – clan heads who had been excluded from the land rights awarded by the British. Tenant security of tenure became conditional on the payment of rents (busuulu) and tributes (envujjo) to Buganda landlords. The British sought to defuse Bataka grievances through the Busulu and Nvujjo law passed in 1928. This regulated rent ceilings, while granting security of tenure to tenant households. However, this remained conditional on the tenants continuing to grow cash crops6. The 1928 law was followed by similar laws in Ankole and Tooro districts in 1938. The laws contributed to “the escalating land conflicts and evictions in the central region, where resolving dual interests of ownership between the registered owner and the lawful or bona fide occupants became impossible”7.

Between 1895-1922 Britain imported 40,000 indentured labourers from India to build the East African railway. Of these, less than 20% remained in the country when their contracts expired. However, over time and with the support of the colonial power, Indians remaining in Uganda formed a thriving merchant class which dominated trade and commerce.

The many territorial and social contestations which characterise Uganda’s complex colonial and post-colonial history have fuelled “multi-level conflicts, embedded in history, social identity, economy and politics”8. While these conflicts invariably involve disputes over land and resources, they “are not simply about plots and boundaries”. It has been strongly argued that the diverse origins and drivers of these deep-seated and localised conflicts “must be unfolded and explored in order to be understood”[9. and to avoid inaccurate generalisation about the state of land governance.

Burnt hut. Photo by Paul Asjes via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0

Uganda gained its independence from Britain in 1962. However, the independence constitution was strongly imprinted by the manipulations of colonial rule. Attempts were made to put in place a hybrid system combining elements of democracy, monarchical rule and a measure of federal autonomy for districts and counties, despite their often-disputed boundaries.

A few years after independence tensions over land and the reach of federal power boiled over. This led to the exiling of the Buganda , or king. Milton Obote, prime minister at Independence assumed the presidency and soon declared Uganda to be a one-party state. All of the Buganda Kingdom land was confiscated by the central government in 1967 and vested in the Uganda Land Commission. The longstanding Bunyoro Kibaale land dispute was also resuscitated during this period when following a referendum, the two ‘lost counties’ of Buyaga and Bugangaize voted to return to Bunyoro control.

Obote was deposed in a military coup in 1971 which brought Idi Amin to power. Amin’s brutal dictatorial rule, which lasted until 1979 was catastrophic for Uganda and elevated ethnic tensions which would scar the country for years to come. Amin purged the army and police of Acholi and Langi soldiers, who he deemed to be loyal to deposed President Obote through a series of barrack massacres. The military also targeted thousands of civilians from ethnic groupings considered hostile to Amin’s rule. It is estimated that over 100,000 people were killed in the first two years that Amin was in power10. In 1973 Amin gave all Indians who were non-citizens three months to leave the country, imposing strict limits on the cash and possessions that they could take with them. Some 70,000 people were deported, forced to leave their properties and businesses behind.

In the last years of his despotic rule Amin sought to annex part of Tanzania, prompting a regional conflict which led to his overthrow in April 1979. This brought a new Acholi elite to power under the Okello presidency for a brief period of interim governance. The following year Obote regained the Presidency, following disputed elections. Obote retained power for five years before he was overthrown by rebel forces of the National Resistance Army (NRA) led by Yoweri Museveni, who was installed as president in 1986. Despite his characterisation of historic kingdoms in Uganda as ‘feudal relics’ Museveni restored the abolished kingdoms in 1993, giving them recognition as traditional institutions.

In Uganda today there are continuing struggles over the control of mailo land in the Buganda kingdom. One commentator has characterised this as “a tussle for power between an indigenous kingdom and an authoritarian state”11. However it needs to be recognised that mailo tenure rights only apply to 9% of the land in Uganda, so this statement needs to be understood in context.At the time of writing Museveni has been in power for 36 years. Although elections have been held there is widespread evidence of sustained suppression of political opposition. A recent constitutional amendment removed limits on the number of terms which can be served by the president12.

Rural shop with election poster. Photo by Gloria via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0

A range of rebel militias have driven conflict in post-independence Uganda. Since Museveni came to power, the most prominent and long-standing conflict was with the so-called Lord’s Resistance Army in Northern Uganda. Fighting between the LRA, local people and government lasted from 1990-2005. Ostensibly the LRA sought to defend Acholi interests against the Museveni government, while advocating governance by the ten commandments. However, the LRA became parasitic on its supposed Acholi constituency, degenerating into extreme warlordism, dependent on random killing and abduction for the forced recruitment of child soldiers.

At its peak this conflict displaced more than 900,000 people into massive and densely settled protected villages. In some sub-regions between 30 percent and 90 percent of the population were interned in camps for internally displaced people (IDPs), for decades13. This negatively affected the social fabric of Ugandan society, both in and beyond the region. Since 2005 land disputes have been a prominent feature in post-conflict Acholiland, as internally displaced people were encouraged to return “to wherever the war found them”.

Pabbo IDP camp 2005. Photo by John and Melanie via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0

The drought-prone Karamoja District in the north-eastern corner of Uganda, between South Sudan and Kenya has a long history of conflict over land, mobility and the rights of pastoralists to natural resources14. This conflict has been amplified by severe drought and rangeland degradation, exacerbated by climate change and armed cross-border cattle raiding. There has been an “explosion in conflicts over land”15. in this area which has hampered resettlement efforts. Currently more than half a million people are reported to be going hungry, following crop failures and social upheaval.

The Kibaale land dispute also remains unresolved. Land conflicts in Hoima, Kibaale and Masindi Districts erupted in 2005, which were reported to have an ethnic dimension, pitting Banyoro against non-Banyoro. A commission of enquiry which was appointed in 2005 found that camps established in the 1970s and 1990s to resettle people displaced from conflicts in other regions had contributed to further polarisation and conflict in Kibaale. The alienation of Bunyoro land for forest reserves and national parks was also reported to be a source of tension. The enquiry also implicated several senior politicians and rich Banyoro in land grabbing and illegal evictions16.

As Uganda’s 2013 Land Policy has acknowledged “land disputes and conflicts broke across national boundaries, spread to tribal and ethnic groupings and merged with current phenomena to generate overwhelming uncertainties in land rights resulting in tenure insecurity”17.

Social tensions within Uganda intersect with complex conflicts which have resonated throughout the Great Lakes region and beyond. In 2022 Uganda was reported to host the largest refugee population in Africa18. This includes displaced people from six countries including South Sudan (927,823), DRC (433,747), Somalia (59,197), Burundi (41,624) Rwanda (26,108) and Eritrea (24,631)19. Land Portal profiles of Somalia, Burundi, Rwanda and the DRC provide insights into the issues facing the region as a whole.

Land policy and legislation

This section explores land policy and law enacted since Ugandan Independence.

The 1965 Land Acquisition Act provides for compulsory acquisition of land for public purposes. The Act sets out procedures for compulsory land acquisition. In 1969 the Public Lands Act vested all lands held under customary tenure in the Land Commission.

In 1975 Amin declared that all land in Uganda was public land. Amin’s Land Reform Decree converted all land into state leasehold. However, reportedly Amin’s decree was largely ignored20.

As noted above Museveni restored the Kingdoms of Uganda in 1993. The Traditional Rulers (Restitution of Assets and Properties) Act, 1993 sought to return some assets and properties specified in its schedule to Traditional Rulers. However, in practice very little restoration took place.The 1995 Constitution vests the overall ownership of land in Ugandan citizens, while the State acts as a trustee, particularly of natural resources, minerals and petroleum. Following the promulgation of the 1995 Constitution of Uganda (Art. 237) earlier land laws have since been challenged in Ugandan courts as being inconsistent with the constitution.

The Constitution recognised four land tenure systems: Customary, Leasehold, Freehold and Mailo. The Constitution provided that holders of land under customary tenure should be able to acquire certificates of customary ownership which could be converted to freehold. The 1995 Constitution also paved the way for the establishment of such institutional structures as District Land Boards (DLBs), the Uganda Land Commission (ULC) and Land Tribunals (LTs). Under Article 273(2)(a), the Constitution empowers the Government to compulsorily acquire land. But this power is subject to Article 26 of the Constitution. Article 26 provides that every person has a right to own property and the right will not be taken away, except if the taking of possession is necessary for public use or in the interest of defence, public safety, public order, public morality and public health; and only if there is prompt payment of fair and adequate compensation.

The 1998 Land Act (with accompanying Amendment Acts 2004 and 2010) and Land Regulations of 2004 sought to clarify the various categories of tenure created by the Constitution and give effect to their administration. The Land Act sets out the powers, procedures and functions of Land Boards and tribunals, and enables the establishment of Communal Land Associations (CLAs) to manage and protect group interests on communal land.

It guarantees security of occupancy on registered land to lawful and bona fide occupants. The Act seeks to enable formalisation of traditional land rights and to accelerate the transition to freehold tenure21. This had been the recommendation of a 1998 land tenure study sponsored by the World Bank and USAID, which advocated the promotion of freehold tenure throughout Uganda to create a land market and encourage investment22.The Act elaborates the procedures through which land occupiers in different tenure settings can apply for a certificate of customary tenure. This enables the rights of transfer and mortgage but requires that these remain consistent with customary norms. There is an option to convert the certificate to freehold, but this requires that the land parcel is surveyed.

The Land Act also governs valuation and compensation where land is acquired in the public interest. Section 42 allows government or local government to acquire land in accordance with Articles 26 and 237(2) of the Constitution. The valuation of customary land is determined either by the open market value of the unimproved land, or by calculating the replacement cost. A disturbance allowance is also normally paid for loss of access to the source of livelihood.

The 1998 Act established a multipurpose Land Fund. The fund sought to correct historical land injustices dating back to the colonial times. In part the fund was to support customary tenants to obtain certificates of occupancy and to compensate mailo landowners whose rights would be diminished by this process. [23. In practice the Land Fund was poorly financed, restricting the buy-out of land from mailo landowners.In 2001 a national Land Policy Working group was established to develop a comprehensive land policy for Uganda. This was the start of a 12-year process to finalise a land policy document.

Rural cultivation. Photo by Mer via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0

Further legislation in the form of the Land (Amendment) Act of 2004 sought to streamline the structures of the land administration system, clarify the jurisdiction of Local Council Courts, and provide for security of occupancy for spouses on family land. The 2004 Amendment to the Land Act attempted further to formalise the relationship between tenants on registered land and landowners by regulating ground rent. The Land (Amendment) Act of 2010 was passed to rectify weaknesses in the original Land Act by criminalizing illegal evictions of bona fide and lawful occupants. It sought to provide a framework to ensure workable relationships between tenants on registered land and the landowners. It also provides penalties of up to 7 years’ imprisonment for violation of the Act.

A National Land Conference was held in 2010 in order to concretise “a transformed Ugandan society through optimal use and management of land resources for a prosperous and industrialized economy with a developed services sector”24.

The resultant 2013 Uganda Land Policy acknowledges that “post-independence and recent attempts to settle the land question by the Land Decree (1975), the 1995 Constitution of Uganda, and the Land Act (1998) failed to deal with fundamental issues in land tenure”25. It highlighted needs for administrative Land Tribunals and the creation of special divisions in both the Magistrate’s Courts, and the High Court, for handling land disputes. It sought to define and categorise land as private land, public land and government land, while recognising customary tenure to be at the same level as other tenure systems.

The policy sought to establish a land registry to register land rights under customary tenure, while resolving to “disentangle the multiple, overlapping and conflicting interests and rights on mailo tenure and “native” freehold tenure26. It also recognises the rights of minority ethnic groups to ancestral land, together with those of pastoral communities. The policy also committed government to pass legislation in the form of a matrimonial property law to protect the land inheritance rights of women. With regard to land confiscated from traditional rulers in 1967, the policy commits the state to “conclusively return” all such properties “upon proof of claims”27.Despite the commitment to secure customary tenure, the Minister of Lands stated in 2014, that land reforms should focus on changing the Ugandan mindset to “stop looking at land as a cultural and social commodity, but as an economic commodit”28.

A four-year Land Probe Commission submitted its report to the President in 2019. The key recommendation that emerged from this report was the need for all land in Uganda to be registered as this would minimize land disputes, enhance tenure security, create avenues for optimal land usage and ultimately result in economic growth. It proposed the introduction of a customary freehold, enabling the registration of certificates of customary title29. There was also thought of abolishing Mailo land but this was not enacted.

The report also recommended the merging of all existing land administration institutions to establish the Uganda Land Services Bureau (ULSB). This commission also proposed the introduction of a tax on idle land, that was to be levied on privately owned large tracts of land of half a square mile (320 acres) and this would be designed to drive the landowner to better utilize the land.

In order to address land disputes, the commission recommended that land and environmental courts are established, while district land tribunals (DLT’s) should be reinstated, presided over by an individual fit to be a magistrate. The commission also recommended the establishment of a land ombudsman in charge of institutions responsible for civil and criminal investigative prosecutions to address land matters. It proposed that the ombud should be given special powers to prosecute eviction complaints and secure relief.

A national land bank was also recommended to operate under the Uganda Lands Services Bureau (ULSB) to acquire land prior to and in accordance with the development agenda submitted to the National Planning Authority (NPA). With regards to mineral discovery and extractives, the commission recommended that a strong legal framework is established to check the pervasive corruption and to protect the rights of local communities that are impacted by these investments, while safeguarding their livelihoods against land grabbing by powerful individuals in the sector30.

Land tenure classifications

Uganda’s Constitution and the Land Act provide that land may be held under four tenure categories: Customary, Leasehold, Freehold and Mailo.

Customary land tenure systems vary from community to community and are prevalent in the northern and eastern regions. Some of the main variations include the systems developed in the Buganda, Bunyoro, Toro and Ankole subregions, where land is vested in a hereditary leader in trust for the recognised members of the social grouping. Elsewhere clan related systems remain in Acholiland and Kigezi sub-regions, while nomadic tenure and grazing access systems predominate in the Karamoja region in the northeast31 Overall however instances where the clan holds land on behalf of communities has significantly diminished. Powers over land on customary land is vested at family level, especially in Kigezi region.

Ankole cattle. Photo by NeilJS via Flickr CC-BY

The underlying commonality in all customary holdings is that rights are derived through recognised membership in a community. These rights are accompanied by reciprocal obligations in that community. Customary rights in land can also be transferred through inheritance. In terms of the Land Act communities have the legal right to document the boundaries of their customary lands, agree rules for how they want to manage their lands, and apply to the government of Uganda to register their lands32

Leasehold tenure provides tenure security either by contract, or by operation of the law. It is a form of ownership in which the landlord or lessor grants the tenant or lessee exclusive possession of the land, usually for a defined period, provided that conditions specified in the lease agreement are met and the agreed rent payments are made.

Freehold tenure originated in the colonial period. Freehold property ownership has no limit in time for the landowner and their beneficiaries. The landowner’s use of the land is restricted by the legal framework.

As discussed in the introduction, the mailo land tenure system was introduced by the British in 1900 under the Buganda Agreement in a colonial bid to create a hereditary landed elite. Mailo ownership of registered land means holding title to it in perpetuity and thus it is similar to freehold. Mailo exists in western and central Uganda, with an estimated 9 per cent of the land mass being owned in this way. The mailo system is unique to Uganda. The Kabaka Mailo was land given to the king which is now owned by the Buganda Land Board. Official Mailo was land given to certain officials and it is now also owned by the Buganda Land Board. Private Mailo was land given to around 1,300 people and institutions, such as churches between 1900 and 1908. This land is still owned privately, complete with longstanding tenants, and confusion over the differences between owner and tenant rights has led to conflicts.

Today the mailo system derives its legality from the 1995 Constitution. Both the Constitution and the Land (Amendment) Act 2010 protect lawful occupiers and their successors against arbitrary eviction, whether they occupy mailo, leasehold or freehold lands, provided that the prescribed nominal ground rent is paid.

Mailo tenure enable land to be held in perpetuity; ownership of land may be separated from the ownership of developments made on the land by lawful, bona fide occupants; and the holders of the land may exercise all powers of ownership, subject to the rights of those persons occupying the land at the time of the creation of the mailo title. In practice however, the mailo system creates conflicting interests and overlapping rights to the same piece of land.

Land investments and acquisitions

Large scale land acquisitions are frequently characterised by a lack of transparency and there have been recommendations for urgent measures to improve this33. The majority of Ugandans depend almost exclusively on agriculture for their livelihood and food security34. Museveni has sought to modernise Uganda and has co-operated with the World Bank since 1991. Uganda has endeavoured to attract private investment, both domestic and foreign, in productive sectors of the economy, by creating an enabling investment climate and facilitating investors to access land. The key sectors are agriculture, livestock, energy, petroleum, minerals, water, wildlife, and forestry. Large chunks of land have been acquired for palm plantations, sugarcane growing, and forestry, tea growing and ranching.

Approximately 15% of land in Uganda can be considered to be government land35. As a result investors seek to acquire privately owned land. However much of this land is also occupied by tenants, creating the possibility that landowners may forcibly evicting other rights holders for financial gain. According to the Ugandan Investment Agency and the Land Commission, land identified for investment must be cleared of “squatters” prior to acquisition36.

Hillside cultivation. Photo by NinaR via Flikr CC-BY

Foreigners cannot own land in Uganda—they can only acquire leasehold rights to land (Land Act of 1998, Section 40(1)). A noncitizen of Uganda cannot acquire a lease exceeding 99 years37.From 2004 to 2013 the foreign direct investment (FDI) flows into Uganda increased from $295 million to $1.1 billion. By 2020, the stock of FDI grew to USD 14.5 billion38. The agricultural sector is still dominated by small holder farmers who face significant challenges. Several of these investment deals have had negative consequences for ordinary Ugandans and smallholder farmers whose land rights may be erased. For example, in 2011, the government evicted 20,000 people from the central districts of Mubende and Kiboga to pave the way for a tree planting project by the UK-based New Forests Company39.

In 2013 the Bank approved a $100 million loan to finance the Competitive and Enterprise Development Project, the first component of which was the “implementation of business environment reforms, including land administration reforms”40. The Uganda Investment Authority was mandated to acquire large pieces of land to support private investment in agriculture.

This encouraged a land rush involving foreign and national companies, powerful individuals, and the state. In 2012, seven large-scale land acquisition deals were officially recorded, which by 2016 had risen to twenty-two. Between 2001 and 2009 foreign companies growing export crops, including the German coffee planter Neuman Kaffee Group and palm oil producers Wilmar International and BIDCO, obtained 99-year land concessions. In 2013 Amantheon Agri acquired 7500 ha through lease and sub-lease in northern Uganda. Reportedly however this investment involved a comprehensive and participatory approach to land acquisition to mitigate the risk of disputes.

Overall, however, the Ugandan government has yet to convincingly ensure that investors observe acceptable rules of the game during land acquisition and compensation. Allegations of land grabbing continue to be reported by the Uganda Land Observatory. In 2022 three multinational companies Agilis, Kiryandongo Sugar Company and Great Seasons SMC Ltd were reported to have been implicated in a “land grabbing scandal which has rendered thousands of smallholder farmers homeless in the Kiryandongo district”41.

There is also increased investment in extractive industries, especially petroleum development and mineral exploration. Big blocks of land have been acquired for industrial establishments and infrastructure development. Since the discovery of viable oil reserves in the Albertine Graben area of Uganda, land has been acquired for establishment of an oil refinery and associated facilities.

In April 2021, the Presidents of Uganda and Tanzania signed an agreement to construct the 1,440 km East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP). The $3.55 billion pipeline will stretch from Uganda’s Albertine Graben region to the Tanzanian port of Tanga.

The need for land for several investments has attracted speculative land acquisition in the region which in the majority of the cases is reported to have violated community land rights and left some families landless42.

Land losses without adequate compensation can have calamitous consequences for the majority poor, especially women whose land rights are precarious. Where displacements, evictions, or even compensations, are based on collectives like families and communities it worsens the situation for women. Most of these people are excluded from negotiation and compensation processes. The question of their participation remains unanswered. Many women live under undocumented marital unions and lack written proof of owning land. This reduces their bargaining power in cases of resettlement and related compensations43. The concerns of managing the environment, climate change responses and biodiversity conservation have also become more pronounced as investments on land affect productivity, food security, or investment in surplus production for income generation and export earnings. This has led to a proliferation of multifaceted, multi-level, land conflicts44.

Land use trends

Uganda is among the world's most susceptible countries to climate extremes, such as droughts. Research has begun to explore climate change as a driver of violent conflict45. Conservation is one of the global strategies implemented, ostensibly to protect natural resources. Uganda has received support from a range of international agencies and NGOs to establish protected areas, forest reserves and national parks. However, the conservation model employed has frequently involved fortress conservation, which seeks to exclude and forcibly resettle people from protected areas.

Forest. Photo by Helena van Eykeren via Flickr CC BY 2.0

Several of these struggles have been closely documented. Some, like the forced resettlement of communities within and adjacent to the Mount Elgon National Park have remained unresolved for decades. Mount Elgon is located in eastern Uganda, spanning the Kenya–Uganda border. Originally Crown land, it was settled during the Amin era, but in 1983 the Ugandan forest department forcibly resettled 30,000 people, creating the Benet resettlement area. Since the 1990s this area has been marked by high levels of tenure insecurity, poverty and food insecurity, coupled with soil and water degradation as a consequence of overcrowding46.Local communities continue to resist their displacement through a wide range of strategies characterised as the ‘weapons of the weak’47.– practicing multiple forms of non-compliance48.

In the agricultural sector, the strategic plan (2015/16 - 2019/20) focuses on 12 priority commodities — (bananas, beans, maize, rice, cassava, tea, coffee, fruits, vegetables, dairy, fish, and livestock (meat) and four strategic commodities: cocoa, cotton, oil seeds, and oil palm. Consistent with Uganda’s modernisation pathway the plan seeks to transform subsistence farmers (growing for consumption) into enterprise farmers (growing for consumption and responding to market needs) and transform small-holder farmers into commercial farmers. This has implications for land access and use and underpins large scale land acquisitions.

Women’s land rights

The Land (amendment) Act of 2004 was enacted to streamline the structures of the land administration system, clarify jurisdiction of Local Council Courts, and provide for security of occupancy for spouses on family land.

The key challenge of land governance today lies in transactions involving communally owned resources, where rights and interests of defenceless persons are frequently overlooked by powerful individuals, groups, and organizations. Large-scale acquisitions seem to be unstoppable since they usually involve global pressure, use of force, and state-capital collusion. This complicates the terrain for women, youth, children, the disabled, the sick and the elderly. This worsens where displacements, evictions, or even compensations, affect families and communities.

Tuckshop trader. Photo by Louis Reynolds via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0

Women and members of marginal households are frequently excluded from negotiation and compensation processes. Many women live under undocumented marital unions and lack proof of owning land. This reduces their bargaining power in cases of resettlement and related compensations. However recent legal action by Advocacy for Women in Uganda successfully challenged the constitutionality of Section 27 of the Succession Act on the grounds that it discriminated against women. Amendments to the Act recently signed into law in 2022 now state that a woman, whether married or divorced, has a claim to their partner’s estate, “especially on things achieved while the marriage subsisted”49.

Urban tenure issues

In 2018 Kampala was growing at a rate of 3.9% per year with a resident population of 1.5 million, but a daily workforce of 4.5 million people50– the majority commuting from the urban periphery. The complex land and urban tenure regime51. is cited as “one of the most binding structural constraints to urban planning… and, as a consequence, investment and urban land re-development in Kampala has been slow”52. In 2015 Kampala was the second fastest growing city in East Africa53. By 2022 the population of Kampala had risen to 3.6 million of which 40% was housed informally.

Kampala. Photo by Slumdweller International via Flickr CC-BY

Community land rights

As can be observed from the previous sections, land related disputes and conflicts in Uganda remain a significant challenge. There are still many evictions, arbitrary land dispossessions, disputes and conflicts across national boundaries, as well as land-related disputes at the household level. These tensions cut across all social groupings and contribute to the prevalence of uncertainties concerning the security of land rights. Some communities have lost their ancestral land rights due to infrastructural projects, large scale agricultural investments, and wildlife conservation.

Land conflicts in Uganda are conservatively estimated to affect seven per cent of agricultural landholdings. This reflects mismatches between the land policies, the legal framework, and implementation processes. These conflicts mirror intra-regional and ethnocentric tension, most in sub-regions like West Nile, Acholi, Lango, Karamoja, Buganda, Teso, Bunyoro, Rwenzori, Ankole, Bukedi and Sebei.

Most cases of the land conflicts arise from social displacement, and subsequent perceptions of trespass associated with illegal settlement by strangers on communal lands. At individual household level, most conflicts arise from disagreements over inheritance in estates of the deceased, or between landowners and bona fide occupants. There is now a growing trend of conflict between government, investors and communities. Most of these conflicts negatively impact livelihood and food security, because disputed lands may be rendered inaccessible for productive use.

Government’s remedial actions include review and amendment of land-related laws that may be out-dated and in conflict with the Constitution and provisions in various international instruments, as well as measures of enforcement and regulations to enhance land access alongside judicial mechanisms for addressing land.

The Land Inquiry Commission uncovered several conflicts in their investigation. This has triggered legislative reform to clarify the relationship between land ownership and land acquisition for development. The National Land Use Policy, National Land Policy, and the National Land Acquisition, Resettlement and Rehabilitation Policy are key responses to reform legislation, land management institutions, guidelines and regulations.

In addition, a total of 21 ministry zones have been established with one-stop centres for the extension of land services to local communities. These Zones/Centres are supported by a computerised land registry with an evolving Land Information System (LIS).Uganda has a vibrant civil society with local and international organisations focused on a range of land, human rights and livelihood related issues. However civil society organisations are under serious pressure from authoritarian rule in Uganda which seeks to neutralise all forms of opposition54.

Land governance innovations

Uganda is part of the United Nations Committee on World Food Security (CFS) and endorsed the VGGT on 11 May 2012.

Uganda has implemented a series of national multi-stakeholder workshops and capacity development initiatives to support the implementation of the VGGT in the country. In addition, a pilot project for documenting and certifying customary rights, which is now informing the roll-out of a follow-up project financed by the UN Capital Development Fund. In addition, 56 Forest Management Plans were validated by communities/private forest holders and district authorities and approved by district councils.

Timeline – milestones in land governance

12th century- Buganda kingdom established

14th century- Bunyoro and other kingdoms established

1894- Uganda declared a British Protectorate

1900- Buganda agreement creates mailo tenure on half of Uganda’s land as Britain seeks to consolidate a hereditary ruling class

1928- The Busulu and Nvujjo law passed to regulate landlord tenant relations

1962- Uganda obtains independence

1965- The Land Acquisition Act provides for compulsory acquisition of land for public purposes

1967- Ugandan kingdoms are abolished by the Obote government and land is held by the Uganda Land Commission

1971- Idi Amin comes to power following a coup

1979- Amin deposed

1980- Obote restored to power

1986- Obote overthrown by Yoweri Museveni

1990- Conflict begins between Ugandan state and the Lord’s Resistance Army in Northern Uganda

1993- The Traditional Rulers (Restitution of Assets and Properties) Act, 1993 restores the kingdoms

1995- The Constitution establishes District Land Boards (DLBs), the Uganda Land Commission (ULC) and Land Tribunals (LTs) However the land tribunals are non-functional in Uganda today

1998- The Land Act passed

2001- A national Land Policy Working group established to develop a comprehensive land policy for Uganda

2004- Land Regulations developed

2005- Conflict in Northern Uganda comes to an end

2010- National Land Conference The Physical Planning Act passed providing for the development and implementation of a national physical planning policy, and the regulation of physical planning activities

2013- National Land Policy

2015- Presidential Land inquiry Commission established

2019- Land Inquiry Commission presents report

2022- Succession (Amendment) Act enlarges women’s property rights

Where to go next?

There is a wide-ranging literature on land related issues in Uganda. Much of it is highly specialised and regionally specific. Two handbooks on land rights and tenure by USAID and SAFE (2014) and LEMU and Namati (2016) provide useful overviews. A special issue of the Journal of Peace and Security Studies – Unfolding land conflicts in Northern Uganda, published in 2013 provides dated, but important insights into the relationship between conflict and land insecurity. Matt Kandel has published in depth research into the post conflict politics of land in north-eastern Uganda.

The work of Emmanuel Nkurunziza provides detailed analysis of how underlying tenure relations have impacted on urban planning and development in Kampala. A recent article in Foreign Policy by Liam Taylor "How Land Reform Became Uganda’s Most Controversial Problem" provides accessible perspectives on unresolved struggles over land.

There is also a useful body of work on large scale land acquisitions in Uganda including that of Stickler (2012) and Nakayi (2016). Oxfam (2022) recently published report Doing business on uneven ground provides a valuable case study of community company dispute resolution in the Kiboga and Mubende districts of Uganda.[55] See the reference list for more information and also explore full text resources available on the Land Portal.

References

[1] Doyle, S. (2006). "From Kitara to the Lost Counties: Genealogy, Land and Legitimacy in the Kingdom of Bunyoro, Western Uganda." Social Identities 12(4): 457-470.

[2] Mamdani, M. (1975). "Class struggles in Uganda." Review of African Political Economy 2(4): 26-61.

[3] Atuhairwe, R. (2019). British divide and rule policy in Uganda. The Observer. Kampala.

[4] Mamdani, M. (1975). "Class struggles in Uganda." Review of African Political Economy 2(4): 26-61.

[5] Green, E. D. (2006). "Ethnicity and the politics of land tenure reform in central Uganda." Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 44(3): 370-388.

[6] Mamdani, M. (1975). "Class struggles in Uganda." Review of African Political Economy 2(4): 26-61.

[7] Government of Uganda (2013). The Uganda National Land Policy, The Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development.

[8] Whyte, M., Q. Gausset and P. Henriques (2013). "Unfolding land conflicts in Northern Uganda: Introduction." Journal of Peace and Security Studies 1. P.4

[9] Ibid. P.4

[10] World Peace Foundation. (2019). "Mass attrocity endings: Uganda Idi Amin 1971 - 1979." Retrieved 29 July, 2022, from https://sites.tufts.edu/atrocityendings/2019/12/20/uganda-idi-amin/.

[11] Taylor, L. (2021). "How Land Reform Became Uganda’s Most Controversial Problem." Retrieved 1 August, 2022, from https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/10/15/uganda-buganda-kingdom-land-reform-debate-museveni-colonialism-indigenous-power/.

[12] Kronke, M. (2022). Broad support for multiparty elections, little faith in electoral institutions: Uganda in comparative perspective. Afrobarometer Policy Paper No. 79, Afrobarometer.

[13] Gelsdorf, K., D. Maxwell and D. Mazurana (2012). Livelihoods, basic services and social protection in Northern Uganda and Karamoja, Working Paper.

[14] Niamir-Fuller, M. (2001). Conflict management and mobility among pastoralists in Karamoja, Uganda. Conflict and Cooperation in Participatory Natural Resource Management, Springer: 19-38.

[15] Kandel, M. (2016). "Struggling over land in post-conflict Uganda." African Affairs 115(459): 274-295.

[16] Malaba, T. (2007). Bunyoro Land Commission Implicates Senior Politicians in Land Grabbing. Kampala, Uganda Radio Network.

[17] Government of Uganda (2013). The Uganda National Land Policy, The Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development. P.2

[18] Opportunity International. (2022). "Where we work: Uganda." Retrieved 27 July, 2022, from https://opportunity.org/our-impact/where-we-work/uganda-facts-about-poverty.

[19] CIA World Factbook. (2022). "Uganda: Refugees and internally displaced persons." Retrieved 27 July, 2022, from https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/uganda/#terrorism.

[20] Hunt, D. (2004). "Unintended consequences of land rights reform: the case of the 1998 Uganda Land Act." Development policy review 22(2): 173-191.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Government of Uganda (2013). The Uganda National Land Policy, The Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Anyuru, M., A. , R. Rhoads, O. Mugyenyi, J. Ekwenyu and T. Balemesa (2016). Balancing Development and Community Livelihoods: A Framework for Land Acquisition and Resettlement in Uganda. Policy Research Series, No. 75, ACODE.

[29] Land Watch. (2020). "All land needs to be registered – Land Probe Commission recommends." Retrieved 2 August, 2022, from https://www.landnet.ug/landwatch/all-land-needs-to-be-registered-land-probe-commission-recommends/.

[30] This summary of the key recommendations of the Land Probe Commission was provided by Brian Makabayi

[31] USAID and SAFE (2014). Land Rights Handbook: Draft, USAID.

[32] LEMU and Namati (2016). Community Guide: How to protect your community's land and resources. Kampala, Uganda, LEMU and Namati.

[33] Stickler, M. M. (2012). Governance of large-scale land acquisitions in Uganda: The role of Uganda Investment Authority, Africa Biodiversity Collaborative Group.

[34] Government of Uganda (2015). Second National Development Plan (NDPII) 2015/16-2019/20. . Entebbe, Uganda.

[35] Stickler, M. M. (2012). Governance of large-scale land acquisitions in Uganda: The role of Uganda Investment Authority, Africa Biodiversity Collaborative Group. P. 15

[36] Ibid.P.16

[37] Ibid.

[38] Lloyd's Bank. (2021). "Foreign Direct Investment in Uganda." Retrieved 2 August, 2022, from https://www.lloydsbanktrade.com/en/market-potential/uganda/investment.

[39] Oakland Institute (2014). World Bank's Bad Business in Uganda. Our land - Our business.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Witness Radio. (2022). "A land grab case against Agilis Ranch 20 and 21 Limited kicks off next week." Retrieved 4 August, 2022, from https://witnessradio.org/a-land-grab-case-against-agilis-ranch-20-and-21-limited-kicks-off-next-week/.

[42] Kuteesa, A. (2014). "Local Communities and Oil Discoveries: A Study in Uganda’s Albertine Graben Region." Retrieved 2 August, 2022, from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2014/02/25/local-communities-and-oil-discoveries-a-study-in-ugandas-albertine-graben-region/.

[43] Nakayi, R. (2016). Interrogating Large Scale Land Acquisitions and Land Governance in Uganda: Implications for Women’s Land Rights.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ide, T., J. Schilling, J. S. Link, J. Scheffran, G. Ngaruiya and T. Weinzierl (2014). "On exposure, vulnerability and violence: spatial distribution of risk factors for climate change and violent conflict across Kenya and Uganda." Political Geography 43: 68-81.

[46] Himmelfarb, D. K. (2012). In the aftermath of displacement: A political ecology of dispossession, transformation and conflict on Mount Elgon, Uganda. PhD, University of Georgia.

[47] Scott, J. (1985). Weapons of the weak: Everyday forms of peasant resistance, Yale University Press.

[48] Norgrove, L. and D. Hulme (2006). "Confronting conservation at Mount Elgon, Uganda." Development and change 37(5): 1093-1116.

[49] Paliament of the Republic of Uganda. (2022). "What new amendments to the Succession Act mean." Retrieved 4 August, 2022, from https://www.parliament.go.ug/news/5646/what-new-amendments-succession-act-mean.

[50] Ngoga, T. H. (2018). The potential for tenure-responsive land use planning in Kampala, International Growth Centre.

[51] Nkurunziza, E. (2007). "Informal mechanisms for accessing and securing urban land rights: the case of Kampala, Uganda." Environment and Urbanization 19(2): 509-526.

[52] Ngoga, T. H. (2018). The potential for tenure-responsive land use planning in Kampala, International Growth Centre.

[53] World Bank Group (2015). Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities: Kampala, Uganda, Urban Environmental Profile, World Bank.

[54] Human Rights Watch. (2021). "Uganda: Harassment of Civil Society Groups." Retrieved 3 August, 2022, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/08/27/uganda-harassment-civil-society-groups.

[55] Cole, C. C. and S. Burgos (2022). Doing business on uneven ground: Advancing land equality is key to addressing climate change and farmer rights. Issue 2: Briefings for Business on inequality in food value chains. UK, International Land Coalition and Oxfam.

Authored on

15 mei 2023