By Marie Gagné, reviewed by Gabin Korbéogo, Groupe de recherche sur les initiatives locales (GRIL) of the Joseph Ki-Zerbo University of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

This is a translated version of the country profile originally written in French

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country in West Africa whose economy is heavily dependent on the primary sector. Cotton production traditionally represented the country's economic engine, but the sector has declined in recent years.In 2018, the country lost its position as Africa's leading cotton producer, ranking third in 2020-2021, behind Côte d'Ivoire and Benin1. Although agriculture employs 80% of the working population, the contribution of the agricultural, forestry and fisheries sectors has declined from 28% of GDP in 1990 to 20% in 20202.

Burkina Faso has a long tradition of artisanal gold panning, which began even before colonization, at least since the 15th century.

Ouagadougou, photography by Thierry Draus, Some rights reserved license CC BY 2.0 DEED

For more than a decade, Burkina Faso has experienced an unprecedented mining boom. Gold displaced cotton as the country's leading export in 2009 and now accounts for almost two-thirds of foreign exchange earnings. The mining sector's contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) has risen from less than 1% in 2009 to 12.7% in 20203. Gold mining, is also a source of direct or indirect income for 20% of the Burkinabe population4.

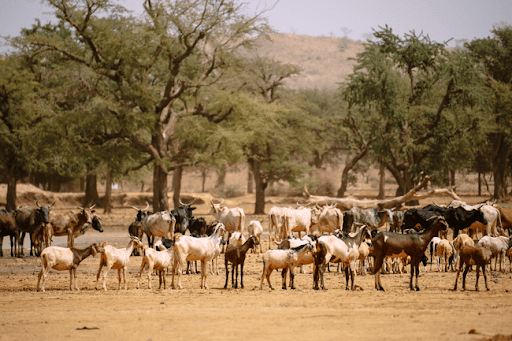

Burkina Faso has the second largest livestock population in West Africa, behind Mali. Livestock is the third largest sector in the Burkina Faso economy, contributing 12% of GDP and 19% of exports5. Livestock and dairy production is also used for local consumption. Livestock production in Burkina Faso is practiced extensively or, more often, in conjunction with agriculture. This is known as agro-pastoralism. The vast majority of rural households 91% own ruminants, illustrating the contribution of livestock to the livelihoods of the Burkinabe population6.

Despite sustained economic growth averaging 5-6% per year, partly linked to the boom in the industrial mining sector, poverty remains high in Burkina Faso. The country ranks 182e among 189 countries and territories on the Human Development Index in 20197.

The land issue in this country is marked by paradoxical trends. On the one hand, the Burkinabe government has adopted an innovative legal framework that recognises customary rights and aims to structure the territory through various developments (pastoral areas, installation of dams, irrigated agricultural areas, protected areas). On the other hand, these policies are accompanied by the weakening of access to land by local users, both in rural and urban areas. This weakening is due in particular to the expansion of large-scale mining and agricultural activities, environmental degradation, demographic growth, migratory flows, the rise of terrorist violence and land accumulation and speculation practices by private real estate companies. Conflicts between various land uses (subsistence agriculture, agro-industry, pastoralism, conservation, gold mining, industrial mining and housing) are leading to growing land insecurity. Thus, 44% of the Burkinabe population feels that their property rights are not adequately protected8.

Historical context

Burkina Faso is a former French colony called Upper Volta at the time. France essentially conceived the territory as a labour pool for cotton cultivation in Sudan, plantations in Côte d'Ivoire and mines in Niger. On the eve of independence, the colonial power relaxed the presumption of domaniality (i.e. the notion that unregistered land recognised by a land title belongs to the State) to recognise customary land rights in all its French colonies.

After the country's independence in 1960, Upper Volta generally maintained these land tenure policies. The State remains the owner of 'vacant and unowned' land. However, the government can only acquire land by 'amicable transfer or expropriation in the public interest' after an enquiry has been carried out to establish whether there are any customary rights to the land in question9.

Thomas Sankara came to power in 1983 in a coup. Upper Volta became Burkina Faso in 1984. In the wake of the revolution, Sankara promulgated the Agrarian and Land Reorganization Act on 4 August 1984. This law marks a paradigm shift and establishes a national land domain making the state the eminent owner of land. In so doing, this law ceased to recognize customary land rights and abolished individual private property, granting owners only rights of use without the possibility of transfer.

After the assassination of Sankara in 1987, Blaise Compaoré became president of Burkina Faso. The government introduced various reforms that gradually modified the 1984 law to facilitate access to private property while maintaining the state as the owner of the national land domain. These reforms were part of the structural adjustment programmes promoted by the World Bank

and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to liberalise the economy and reduce the role of the state. However, given the ineffectiveness of these measures, in particular Law No.o 014/96/ADP on agrarian and land reorganization in Burkina Faso in 1996, the government once again changed its approach.

From 1998 onwards, the country embarked on a process of reflection and pilot operations to recognise customary land rights10. Following a concerted approach with all stakeholders at the regional and national levels, the government promulgated Law No.o 034-2009/AN of 16 June 2009 on rural land tenure in Burkina Faso11. At the same time, however, the state has been encouraging private investment in agriculture.

A popular uprising forced President Blaise Compaoré out power in October 2014. The movement represents the culmination of the population's growing dissatisfaction with Compaoré's government, a dissatisfaction that dates back to the 1998 murder of Norbert Zongo, a journalist critical of the government. Roch Marc Christian Kaboré won the presidential elections in November 2015 and was re-elected in 2020. Since 2016, the country has been grappling with a rise in violence that has caused thousands of deaths and the displacement of more than 1.5 million people12. In the countryside, the proliferation of non-state armed groups linked to jihadist movements threatens the security of agricultural producers, herders and employees in the mining sector. This instability led to the overthrow of President Kaboré in January 2022, following a military coup by the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration.

Land legislation and regulations

Legislation differs for rural land and mineral subsoil.

Rural lands: In 2002, the government introduced a law on pastoralism that guarantees herders "the right of access to pastoral areas, the right of equitable use of natural resources and the

mobility of herds"13. To support this sector, the government has also created 27 pastoral zones covering thousands of hectares, of which about ten are actually operational.

Law No.o 034-2009/AN of 16 June 2009 recognizes customary land rights and transfers land management powers to rural communes. The recognition of the rights of rural populations to their land, either individually or collectively, is done through the rural land possession certificate (APFR). The APFR constitutes a "title of enjoyment" that can be transmitted, transferred or eventually transformed into a property title. In addition, the law allows for the elaboration of "local land charters" by the populations themselves in order to adapt the legal provisions to the practices and rules of their community14. On the whole, the law adequately protects customary rights, but it nevertheless excludes migrants from access to certificates of land possession in its Article 3615.

Law No.o 034-2012/AN of 2 July 2012 on agrarian and land reorganization (RAF) in Burkina Faso consolidates the 2009 law. By creating private domains for municipalities and individuals, it marks a break from previous laws that affirmed the principle of eminent domain of the State16.

Although Burkina Faso has a comprehensive and coherent set of land laws aimed at formalizing customary land rights, the process of attestation is slow. More than 90% of agricultural land is not secured by a formal deed. This is partly due to the expansion of newly cultivated land, which is increasing faster than the demand for land certification17. The scale of the expected changes, the weak capacities of decentralised bodies and the lack of legitimacy of the State in land matters also contribute to the predominance of customary rights. For the time being, most certificates are issued within the framework of projects financed by international cooperation, such as the Land Tenure Security Project carried out by the United States Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC).

The mining subsoil: Adopted in 2015, Law No. 036-2015/CNT on the mining code of Burkina Faso provides a framework for both artisanal gold panning and industrial-type mining activities. According to the law, gold miners are required to obtain an artisanal mining authorization,

valid and renewable for a period of two years. The perimeter of artisanal mines varies between one and one hundred hectares.

Industrial mining activities take precedence over gold panning. Article 73 of the law provides that exploration and research may be carried out on sites that have been granted an artisanal mining permit. When an industrial exploitation title is granted on the area concerned, this authorization cannot be renewed. The new operator must nevertheless pay compensation to the former beneficiary of an artisanal permit, although the law does not specify the amount. Gold panning within the perimeter of an industrial mine is only possible if the operator gives permission.

The legislation provides for expropriation mechanisms for industrial mining. The occupation of land for the purpose of prospecting, searching for or exploiting mineral substances entails the payment of "fair and prior compensation" to the owner of the land or its occupier (article 123). Similarly, the owner of the land who has previously carried out work on the area concerned is entitled to reimbursement of the expenses incurred (art. 126)18.

In response to pressure from Burkinabè and international civil society organisations, the new mining code increases development payments to local communities from 0.5% to 1% of their turnover. This money is used to feed the Local Development Mining Fund, to which the state also contributes 20% of its royalties. The law also establishes a Mine Rehabilitation and Closure Fund financed by industrial licensees19.

Land tenure system

Under Law No.o 034-2012/AN of July 2, 2012 on agrarian and land reorganization in Burkina Faso, the national land estate of Burkina Faso is composed of urban land and rural land. Located within the administrative boundaries of cities, urban land is mainly dedicated to housing, commerce, industry, crafts and public services. The occupation of these lands is governed by the urban planning and building code, except for the lands of villages attached to urban municipalities. For their part, rural lands are "intended for agricultural, pastoral, forestry, wildlife, fish farming and conservation activities, located within the administrative boundaries of rural communes and villages attached to urban communes.

In both urban and rural areas, the national land estate is made up of three distinct domains: that of the State, that of local authorities and that of private individuals. State and local authority land holdings are in turn divided into public real estate and private real estate. The land holdings of private individuals consist of all the rights of ownership, enjoyment and use of land and real estate20.

Trends in land use

Burkina Faso's population has grown from 8.81 million in 1990 to 20.9 million in 202021. The population remains concentrated in rural areas, with nearly three out of four people living in the countryside in 2019 (73.7%)22.

Taken as a whole, agricultural land covered 29,748 km2 in 1961 and increased to 121,000 km2 in 201823, or 44% of the territory. However, only part of the agricultural land is actually cultivated. New agricultural land is being developed at the expense of forest cover. Although 14% of the territory is officially protected as forest or nature reserve, satellite data reveal that only 2% of the land was actually covered by virgin forest in 201324.

There are more than one million farms in the country "of which 87% practice subsistence farming and or extensive livestock rearing" for family needs. The most common food crops are millet, sorghum, maize and rice. The western regions of the country (Boucle du Mouhoun, Hauts-Bassins, Cascades) have historically concentrated most of the cotton production, but the east and centre-east have seen an expansion of this crop in recent years25. In recent years, however, the sector has been affected by low rainfall, limited access to inputs, a boycott of production by some producers led by a civil society organization called the Democratic Youth Organization of Burkina, and insecurity in the east preventing farmers from accessing their fields26. In several villages, granaries were burned, crops and livestock were taken away by armed groups, and farmers were banned from production.

Women carrying cotton in Burkina Faso, photo by Ollivier Girard/CIFOR, Some rights reserved

The country is marked by significant internal migration flows, linked to climatic hazards, the expansion of the agricultural front and the socio-political crises that occurred in the 2000s in Côte d'Ivoire, a neighbouring country where millions of Burkinabè have settled. In the 1970s and 1980s, droughts prompted people in the north and centre of Burkina Faso to migrate to the south and west, areas that are sparsely populated but have fertile soil. While pastoralists are looking for pasture, Mossi farmers are attracted to cotton and cashew cultivation. Population movements towards the southwest increased in the 1990s due to the saturation of land in the traditional cotton basin. The return of Burkinabe migrants from Côte d'Ivoire in the 2000s also increased the pressure on land27.

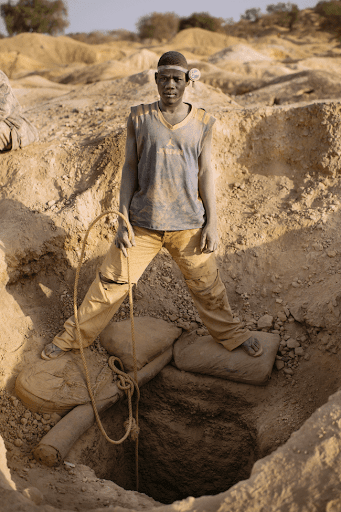

Burkina Faso has a long tradition of artisanal gold panning, which began even before colonization, at least since the 15th century28. The number of artisanal mines has been increasing since the 2000s and currently stands at between 700 and 1000. However, only some 261 sites have an artisanal mining permit. It is estimated that between 600,000 and 1.3 million people work in the sector29. Almost half of the annual artisanal gold production is concentrated in the southwest region, while the northern region hosts a quarter30.

Gold panning gallery in Burkina Faso, photography by Ollivier Girard /CIFOR, Some rights reserved

The number of gold mines has been increasing since 2007, when four industrial mines came on stream. In 2020, the country had 16 industrial gold mines and one zinc mines and planned to open three more mines in 2021. Burkina Faso is the fifth largest mining producer in Africa. The industrial mining sector employs 50,000 people31.

The expansion of gold mining activity is taking place at the expense of agricultural, pastoral and forested areas. In 2018, exploration and industrial mining permits covered almost half of the territory of Burkina Faso32.

Armed groups linked to the Islamic State and al-Qaeda are increasing attacks on artisanal and industrial miners in the context of a weakening state. Terrorist groups use artisanal gold mining as a means to launder money and finance their activities. This type of violence has increased in 202133.

Investments and land acquisitions

Land acquisitions are on the rise in Burkina Faso. Between 2000 and 2012, it is estimated that domestic and foreign investors obtained 288,044 hectares of land. Of these, the bulk (131,442 hectares) was for mining, 43,102 hectares for agribusiness and 113,500 hectares for biofuels34.

Law No.o 014/96/ADP on agrarian and land reorganization in Burkina Faso, which aimed to grant substantive rights to rural land to secure investments, actually made it easier for urban elites to acquire plots of land from customary holders35. This movement has since expanded. In some cases, agriculture is used as a pretext by political leaders or wealthy Burkinabè businessmen to appropriate large areas of land, which are then fenced off without any effective agricultural development.

In addition, the government aims to develop growth poles to encourage private investment, including three agropoles (Bagré, Samendeni and Sourou) and a mixed mining/livestock pole (the Sahel pole). The first pilot project launched in Bagré in 1986, the Bagrépôle, is a hydro-agricultural development of 30,000 hectares declared a public utility zone, with a quarter of the land allocated to family farmers and three quarters to private investors36.

As the subsoil belongs to the state, mining concessions are only granted to national legal entities. Foreign companies therefore have access to the subsoil through Burkinabe-registered companies37. The Burkinabe state holds, free of charge, 10% of the share capital of any industrial mining company exploiting a deposit free of charge and receives dividends on the profits38. The industrial mines are mostly owned by foreign multinationals, including Russian, Australian, Canadian, British and South African companies. The first wholly Burkinabè-owned and financed mine, Salma Mining SA, was granted an industrial mining licence in 2021 in the southwest of the country39.

Community land tenure systems

Agriculture: Traditional management of agricultural land is based on principles common to all ethnic groups in Burkina Faso:

- Since land belongs to God, man has the responsibility to tend to the land without owning it. Therefore, he cannot sell the land. Loans imply only a symbolic gift without monetary consideration.

- The land chief manages the village land on behalf of the community and supervises the sacrifices to invoke the local genies. The land chief is usually from the family of the original settlers.

- Access to land is based on belonging to a lineage made up of large families sharing the same ancestor. Use rights are assigned to the lineage, which is responsible for the distribution of land among its members.

- Land is available open to transhumant migrants and herders, who then enter into a 'tutorat' relationship with the customary landowners. Land loans and other land tenure agreements are normally for an indefinite period, but are terminated when the beneficiary of the use rights ceases to cultivate the allocated plot or does not respect the restrictions imposed (such as avoiding planting trees on the loaned plot).

In a context of monetarisation of exchanges and land saturation, however, land is gradually losing its sacred and inalienable character and is being perceived as a commodity. The traditional forms of access to land through donations and long-term loans are giving way to short-term sales and rentals, particularly in migrant-receiving areas such as the South-West. Land transactions are increasingly carried out at the individual or family level without consulting the customary authorities traditionally responsible for its management. Village land is thus fragmented into land domains administered by lineage chiefs rather than land chiefs. While the purchase of land offers buyers greater security of tenure, temporary loans (lasting from one to three years) increase the insecurity of migrants, young people and women who use them40.

Mining activities: The development of industrial mines often occurs at the expense of the local communities' land rights, causing thousands of people to be relocated from their villages. For example, Essakane, the second largest mine in Burkina Faso covering 100 km2 , has resulted in the involuntary displacement of over 16,000 people. Open-pit mines profoundly alter the landscape, creating huge pits, destroying vegetation, scaring away wildlife, contaminating waterways and groundwater. Overall, residents feel that the establishment of mines near their villages does not improve their living conditions or even contributes to their deterioration. Several demonstrations against industrial mining have been severely repressed by the police authorities41.

The development of industrial mines also hinders artisanal gold mining as most of the deposits are located within the exploration perimeters. Gold miners often operate within these perimeters without authorization, leading to conflicts between them and the industrial mines.

Gold panning is also not without consequences, generating frequent disputes between migrant gold miners and local communities. Artisanal gold mining pollutes the soil and groundwater due to the use of toxic substances such as mercury and cyanide. In addition, gold panning involves turning over hundreds of square metres of land or digging galleries up to 100 metres deep. Both techniques create piles of earth which subsequently make agriculture impossible42.

Open-pit mine in Burkina Faso, photograph by Isuru Senevi, Some rights reserved

Livestock: Livestock breeders in Burkina Faso are faced with increasing land insecurity. The capacity of agricultural areas to accommodate transhumant livestock breeders has decreased significantly due to the increase in cattle numbers and the expansion of agricultural land. This results in damage to crops and conflicts with agricultural producers. In a context of pressure on land, the system of free access to the bush does not offer herders security of tenure insofar as farmers are increasingly tending to exclude them from areas previously reserved for the passage or grazing of animals43.

Conflicts between pastoralists and artisanal gold miners are also common, even where pastoral rights are in principle guaranteed. Herders consider that gold panning hinders the mobility of their herds. The gold panners, on the other hand, argue that they carry out these activities to earn a living without impacting pastoral activities44. Land tenure insecurity is pushing many herders to resume long-distance transhumance or to leave areas where pressure on land is too strong and settle elsewhere in Burkina Faso, or even in Ghana or Côte d'Ivoire.

Herd near Lake Bam in Burkina Faso, photography by Ollivier Girard /CIFOR, Some rights reserved

Women's land rights

From a legal point of view, women's land rights are fairly well protected in Burkina Faso. Article 7 of the 2009 law explicitly states that rural actors must have equitable access to land regardless of gender. According to Article 13 of the same law, local land charters are also expected to define measures favouring "vulnerable groups, in particular women, pastoralists and youth"45. The country's legislation also aims to integrate women into land management through the appointment of two representatives of women's organizations to village land commissions46.

In reality, however, gender inequalities in land access remain pronounced. As in all patrilineal societies, the intergenerational transmission of land takes place through men descending from the same lineage. In Burkina Faso, few women own their land. They are generally granted a plot of land belonging to their husband's lineage. The soil on these plots is often of poor quality and small in area. Some ethnic and religious groups do not allow women to cultivate their own fields. With their husbands' consent, women must therefore in the dry season.

Women's use rights are precarious and revocable. For example, when a young head of household settles or a migrant returns to his village, customary owners tend to take back the plots allocated to women. Women do not take part in decisions about land management, which remains under the control of men47.

At the national level, women represent between 50% and 55% of the agricultural workforce. However, they only farm about 16% of the land. This percentage is even lower in the cotton basin regions, where it vvaried between 7 and 9% in 2020. Women are increasingly resorting to borrowing to access land. In 2020, nearly 57% of the land exploited by women was obtained by loan or lease, while 43% was acquired by inheritance, gift or bequest.

The persistence of customary practices is reflected in applications for certificates of rural land ownership, of which only 3.27% are from women (1,399 out of a total of 42,760 applications registered between 2014 and 2019)48.

Urban Land Tenure

Access to land in urban areas is governed by Law No.o 017-2006/AN on the urban planning and construction code in Burkina Faso and Law No.o 034-2009/AN of 16 June 2009 on rural land tenure in Burkina Faso. The country has 49 urban communes. As in rural areas, land tenure in cities is marked by customary law, informal practices and speculation in connection with the weak presence of the State.

Ouagadougou, photography by Thierry Draus, Some rights reserved

For example, in Ouagadougou, the country's capital and largest city, Mossi traditional leaders are frequently involved in the informal sale of land to real estate agencies or migrants. Those who build their houses on unplotted land, located in spontaneous settlements, hope to have their plots regularized afterwards, but are often threatened with eviction without compensation. In reaction land tenure insecurity in the city, citizens have created several committees to defend the right to housing. Two forms of legitimacy are therefore in conflict in the urban environment: the one claimed by customary chiefs based on their traditional authority and the one based on respect for official rules claimed by newcomers49.

Land innovations

The Burkinabe government is making significant efforts to promote women's access to irrigated plots. In 2020, the government allocated 45.94% of the new developed areas to women, thus exceeding its target of 30%50. In addition, the government seeks to promote women's access to agricultural inputs and equipment. A study reveals that these policies have positive effects and contribute to "food security, economic growth and improved living conditions for women"51.

Timeline - milestones in land governance

1984: Promulgation of Ordinance No.o 84-050/CNR/PRES of 4 August 1984 on agrarian and land reorganization in Burkina Faso

The law establishes the State as the eminent owner of the land following the Sankarist revolution.

2002: Law No. 034-2002/AN of 14 November 2002 on the orientation law relating to pastoralism

This law aims to secure the practice of pastoralism in Burkina Faso.

2009: Adoption of Law No.o 034-2009/AN of 16 June 2009 on rural land tenure in Burkina Faso

This law aims to recognize and formalize customary land rights.

2012: Adoption of Law No.o 034-2012/AN of 2 July 2012 on agrarian and land reorganization in Burkina Faso

This law establishes a land domain for municipalities and individuals. The State is therefore no longer the sole holder of the national land domain.

2015 : Adoption of the Law n° 036-2015/CNT on the mining code of Burkina Faso

This law revises the previous mining codes in order to increase the profits from industrial gold mining.

Where to go next?

The author's suggestions for further reading

To learn more about the complex links between gold mining and terrorist violence in the Sahel, readers can refer to the International Crisis Group's report, Getting a Grip on Central Sahel’s Gold Rush l. It discusses how armed groups, including jihadists, are taking control of gold-mining sites in areas with little state presence in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger.

If you are more interested in agricultural issues, I suggest a scientific article by Souleymane Ouédraogo and Marie-Claire Sorgho Millogo. The authors explain how customary land management systems have adapted to allow the introduction of techniques to combat desertification. Even those who do not own their land are trying to reverse land degradation.

References

[1] Boudani, Yaya. 2021. « Burkina Faso: bilan positif de la campagne cotonnière écoulée ». RFI, 12 mai. URL : https://www.rfi.fr/fr/podcasts/afrique-économie/20210511-burkina-faso-bilan-positif-de-la-campagne-cotonnière-écoulée.

[2] World Bank. 2021. « Country profile : Burkina Faso », World Development Indicators. URL : https://databank.worldbank.org/views/reports/reportwidget.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=BFA.

[3] Sebogo, Mahamadi. 2021. « Secteur minier : ‘Nous allons travailler pour que l’or et les autres métaux brillent pour tous’, Adama Soro, président du CMB ». Sidwaya, 30 juillet. URL : https://landportal.org/news/2021/11/secteur-minier-%C2%AB-nous-allons-travailler-pour-que-l%E2%80%99or-et-les-autres-m%C3%A9taux-brillent.

[4] Medinilla, Alfonso, Poorva Karkare, et Tongnoma Zongo. 2020. Encadrer à nouveau l’artisanat minier au Burkina Faso : vers une approche contextualisée. Maastricht: Centre européen de gestion des politiques de développement (ECDPM). URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/encadrer-a%CC%80-nouveau-l%E2%80%99artisanat-minier-au-burkina-faso.

[5] USAID. 2017. Burkina Faso– Property Rights and Resource Governance Profile. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/usaid-country-profile-property-rights-and-resource-governance.

[6] Minot, Nicholas, et Samara Elahi. 2020. Role of pastoralism in Burkina Faso: Contribution to revenue, food security, and resilience. SNV Voices for Change Partnership. URL : https://snv.org/assets/explore/download/role_of_livestock_report_en.pdf.

[7] PNUD. 2020. « Burkina Faso ». Rapport sur le développement humain 2020. URL : http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/fr/BFA.pdf.

[8] https://www.prindex.net/data/burkina-faso/.

[9] Hochet, Peter. 2014. Burkina Faso : vers la reconnaissance des droits fonciers locaux. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/fiche-pays-no-5-burkina-faso.

[10] Hochet, Peter. 2014. Burkina Faso : vers la reconnaissance des droits fonciers locaux. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/fiche-pays-no-5-burkina-faso.

USAID. 2017. Burkina Faso– Property Rights and Resource Governance Profile. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/usaid-country-profile-property-rights-and-resource-governance.

[11] https://www.foncier-developpement.fr/pays/afrique-de-louest/burkina-faso/

[12] Lanzano, Cristiano, Sabine Luning, et Alizèta Ouédraogo. 2021. Insécurité au Burkina Faso – au-delà des minerais de conflit. Les liens complexes entre l’exploitation aurifère artisanale et la violence. Uppsala: The Nordic Africa Institute. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/inse%CC%81curite%CC%81-au-burkina-faso-%E2%80%93-au-dela%CC%80-des-minerais-de-conflit.

Traoré, Dramane. 2022. « Burkina Faso : le nombre de déplacés internes s’établit à 1 579 976 personnes » Agence Anadolu (AA), 17 janvier. URL: https://www.aa.com.tr/fr/afrique/burkina-faso-le-nombre-de-déplacés-internes-s-établit-à-1-579-976-personnes/2475749.

[13] Loi n° 034-2002/AN d’orientation relative au pastoralisme au Burkina Faso. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/lex-faoc040975/loi-n%C2%B0034-2002an-portant-loi-d%E2%80%99orientation-relative-au-pastoralisme.

[14] Hochet, Peter. 2014. Burkina Faso : vers la reconnaissance des droits fonciers locaux. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/fiche-pays-no-5-burkina-faso.

Loi no 034-2009/AN du 16 juin 2009 portant régime foncier rural au Burkina Faso. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/loi-no-034-2009an-portant-r%C3%A9gime-foncier-rural-au-burkina-faso.

[15] https://www.foncier-developpement.fr/pays/afrique-de-louest/burkina-faso/.

[16] USAID. 2017. Burkina Faso– Property Rights and Resource Governance Profile. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/usaid-country-profile-property-rights-and-resource-governance.

[17] Ministère de l'agriculture et des aménagements hydro-agricoles du Burkina Faso. 2021. Tableau de bord statistique de l’agriculture 2020. Juin. URL : https://www.agriculture.bf/upload/docs/application/pdf/2021-07/tableau_de_bord_agriculture_2020_def.pdf.

[18] Drechsel, Franza, Bettina Engels, et Mirka Schäfer. 2018. « Les mines nous rendent pauvres » : L'exploitation minière industrielle au Burkina Faso. Berlin: GLOCON. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/%C2%AB-les-mines-nous-rendent-pauvres-%C2%BB.

Loi n° 036-2015/CNT portant code minier du Burkina Faso. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/loi-n%C2%B0-036-2015cnt-portant-code-minier-du-burkina-faso.

[19] Loi n° 036-2015/CNT portant code minier du Burkina Faso. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/loi-n%C2%B0-036-2015cnt-portant-code-minier-du-burkina-faso.

USAID. 2017. Burkina Faso– Property Rights and Resource Governance Profile. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/usaid-country-profile-property-rights-and-resource-governance.

[20] Loi no034-2012/AN du 2 juillet 2012 portant réorganisation agraire et foncière au Burkina Faso. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/loi-no-034-2009an-portant-r%C3%A9gime-foncier-rural-au-burkina-faso.

[21] World Bank. 2021. « Country profile : Burkina Faso », World Development Indicators. URL : https://databank.worldbank.org/views/reports/reportwidget.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=BFA.

[22] Ministère de l’Économie, des Finances et du Développement. 2020. « RGPH 2019 : Le Burkina Faso compte 20 487 979 habitants », 22 décembre. URL : https://www.finances.gov.bf/forum/detail-actualites?tx_news_pi1%5Baction%5D=detail&tx_news_pi1%5Bcontroller%5D=News&tx_news_pi1%5Bnews%5D=210&cHash=d4f20bcadd89c7ad2ad4f420b4300dfa.

[23] https://donnees.banquemondiale.org/indicator/AG.LND.AGRI.K2?locations=BF.

[24] USAID. 2017. Burkina Faso– Property Rights and Resource Governance Profile. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/usaid-country-profile-property-rights-and-resource-governance.

[25] Hochet, Peter. 2014. Burkina Faso : vers la reconnaissance des droits fonciers locaux. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/fiche-pays-no-5-burkina-faso.

[26] Engels, Bettina. 2021. « Peasant Resistance in Burkina Faso's Cotton Sector ». International Review of Social History 66 (S29): 93-112. Sylla, Fana. 2021. Cotton and Products Annual. Dakar: United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)-Foreign Agricultural Service and Global Agricultural Information Network (GAIN). URL : https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Cotton%20and%20Products%20Annual_Dakar_Senegal_04-01-2021.pdf.

[27] Gonin, Alexis. 2018. « Concurrences spatiales, libre accès et insécurité foncière des éleveurs (sud-ouest du Burkina Faso) », Cahiers du Pôle Foncier, Montpellier, Pôle Foncier, 33 p. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/concurrences-spatiales-libre-acc%C3%A8s-et-ins%C3%A9curit%C3%A9-fonci%C3%A8re-des-%C3%A9leveurs-sud-ouest.

Nana, Patiende Pascal. 2018. « Du groupe à l’individu : dynamique de la gestion foncière en pays gouin (sud-ouest du Burkina Faso) ». Belgeo (2). URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/du-groupe-a%CC%80-l%E2%80%99individu.

[28] Jean Baptiste Kiethiega, cité dans Bohbot, Joseph. 2017. « L’orpaillage au Burkina Faso : une aubaine économique pour les populations, aux conséquences sociales et environnementales mal maîtrisées. » EchoGéo 42. URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.15150.

[29] Bohbot, Joseph. 2017. « L’orpaillage au Burkina Faso : une aubaine économique pour les populations, aux conséquences sociales et environnementales mal maîtrisées. » EchoGéo 42. URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.15150.

Medinilla, Alfonso, Poorva Karkare, et Tongnoma Zongo. 2020. Encadrer à nouveau l’artisanat minier au Burkina Faso : vers une approche contextualisée. Maastricht: Centre européen de gestion des politiques de développement (ECDPM). URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/encadrer-a%CC%80-nouveau-l%E2%80%99artisanat-minier-au-burkina-faso.

USAID. 2017. Burkina Faso– Property Rights and Resource Governance Profile. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/usaid-country-profile-property-rights-and-resource-governance.

[30] Initiative pour la Transparence dans les Industries Extractives au Burkina Faso. 2021. Rapport ITIE 2019. Tunis: BDO Tunisie Consulting, Février. URL : https://eiti.org/files/documents/rapport_itie-bf_2019_version_finale_signee.pdf.

[31] Coulibaly, Nadoun. 2021. « Or : au Burkina Faso, trois nouvelles mines vont doper la filière en 2021 ». Jeune Afrique, 13 avril. URL: https://landportal.org/news/2021/12/or-au-burkina-faso-trois-nouvelles-mines-vont-doper-la-fili%C3%A8re-en-2021. Sebogo, Mahamadi. 2021. « Secteur minier : ‘Nous allons travailler pour que l’or et les autres métaux brillent pour tous’, Adama Soro, président du CMB ». Sidwaya, 30 juillet. URL : https://landportal.org/news/2021/11/secteur-minier-%C2%AB-nous-allons-travailler-pour-que-l%E2%80%99or-et-les-autres-m%C3%A9taux-brillent.

[32] Drechsel, Franza, Bettina Engels, et Mirka Schäfer. 2018. « Les mines nous rendent pauvres » : L'exploitation minière industrielle au Burkina Faso. Berlin: GLOCON. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/%C2%AB-les-mines-nous-rendent-pauvres-%C2%BB.

[33] Wilkins, Henry. 2021. « Gold Mining in Burkina Faso Becomes Increasingly Dangerous ». Voice of America (VOA), November 09. URL : https://landportal.org/news/2021/11/gold-mining-burkina-faso-becomes-increasingly-dangerous.

[34] COPAGEN, Inter Pares, REDTAC. 2015. Touche pas à ma terre, c’est ma vie ! URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/978-2-9815170-0-5/touche-pas-a%CC%80-ma-terre-c%E2%80%99est-ma-vie.

[35] Hochet, Peter. 2014. Burkina Faso : vers la reconnaissance des droits fonciers locaux. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/fiche-pays-no-5-burkina-faso.

[36] Pelon, Vital. 2019. « Coup d’œil sur l’agriculture et les politiques agricoles au Burkina Faso ». Bulletins de synthèse Souveraineté alimentaire, no30. Inter-réseaux Développement rural. URL : https://www.inter-reseaux.org/wp-content/uploads/bds_burkina_201219-vf.pdf.http://www.bagrepole.bf/qui-sommes-nous/historique

[37] Drechsel, Franza, Bettina Engels, et Mirka Schäfer. 2018. « Les mines nous rendent pauvres » : L'exploitation minière industrielle au Burkina Faso. Berlin: GLOCON. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/%C2%AB-les-mines-nous-rendent-pauvres-%C2%BB.

[38] Loi n° 036-2015/CNT portant code minier du Burkina Faso. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/loi-n%C2%B0-036-2015cnt-portant-code-minier-du-burkina-faso.

[39] Burkina24. 2021. « Salma Mining SA s’implante dans le Sud-Ouest ». 1er mars. URL : https://www.burkina24.com/2021/03/01/burkina-faso-salma-mining-sa-simplante-dans-le-sud-ouest/.

[40] Hochet, Peter. 2014. Burkina Faso : vers la reconnaissance des droits fonciers locaux. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/fiche-pays-no-5-burkina-faso.

Nana, Patiende Pascal. 2018. « Du groupe à l’individu : dynamique de la gestion foncière en pays gouin (sud-ouest du Burkina Faso) ». Belgeo (2). URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/du-groupe-a%CC%80-l%E2%80%99individu.

USAID. 2017. Burkina Faso– Property Rights and Resource Governance Profile. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/usaid-country-profile-property-rights-and-resource-governance.

[41] Drechsel, Franza, Bettina Engels, et Mirka Schäfer. 2018. « Les mines nous rendent pauvres » : L'exploitation minière industrielle au Burkina Faso. Berlin: GLOCON. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/%C2%AB-les-mines-nous-rendent-pauvres-%C2%BB.

[42] Bohbot, Joseph. 2017. « L’orpaillage au Burkina Faso : une aubaine économique pour les populations, aux conséquences sociales et environnementales mal maîtrisées. » EchoGéo 42. URL : https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.15150.

[43] Gonin, Alexis. 2018. « Concurrences spatiales, libre accès et insécurité foncière des éleveurs (sud-ouest du Burkina Faso) », Cahiers du Pôle Foncier, Montpellier, Pôle Foncier, 33 p. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/concurrences-spatiales-libre-acc%C3%A8s-et-ins%C3%A9curit%C3%A9-fonci%C3%A8re-des-%C3%A9leveurs-sud-ouest.

[44] Sidwaya. 2021. « Orpaillage dans la zone pastorale de la Nouaho : Une entrave à la pratique de l’élevage ». 5 octobre. URL: https://landportal.org/news/2021/11/orpaillage-dans-la-zone-pastorale-de-la-nouaho-une-entrave-%C3%A0-la-pratique-de-l%E2%80%99%C3%A9levage.

[45] Loi no 034-2009/AN du 16 juin 2009 portant régime foncier rural au Burkina Faso. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/loi-no-034-2009an-portant-r%C3%A9gime-foncier-rural-au-burkina-faso.

[46] Décret n°2010-404/PRES/PM/MAHRH/MRA/MECV/MEF/MATD du 29 juillet 2010 portant attributions, composition, organisation et fonctionnement des structures locales de gestion foncière

[47] Konaté, Georgette. 2006. « Burkina Faso : une insécurité foncièrement féminine ». Grain de sel no. 36:19. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/burkina-faso-une-inse%CC%81curite%CC%81-foncie%CC%80rement-fe%CC%81minine.

[48] Siribie, Djakaridia. 2021. « Journée de la Femme rurale 2021: La sécurisation foncière au menu ». Sidwaya, 17 octobre. URL: https://www.sidwaya.info/blog/2021/10/17/journee-de-la-femme-rurale-2021-la-securisation-fonciere-au-menu/.

[49] Korbéogo, Gabin. 2021. « Traditional Authorities and Spatial Planning in Urban Burkina Faso: Exploring the Roles and Land Value Capture by Moose Chieftaincies in Ouagadougou ». African Studies no. 80 (2):190-206. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/traditional-authorities-and-spatial-planning-urban-burkina-faso.

[50] Ministère de l'agriculture et des aménagements hydro-agricoles du Burkina Faso. 2021. Tableau de bord statistique de l’agriculture 2020. Juin, https://www.agriculture.bf/upload/docs/application/pdf/2021-07/tableau_de_bord_agriculture_2020_def.pdf.

[51] Souratié, Wamadini, Farida Koinda, Bernard Decaluwé, et Rasmata Samandoulougou. 2019. « Politiques agricoles, emploi et revenu des femmes au Burkina Faso ». Revue d'économie du développement no. 27 (3):101-127. URL: 10.3917/edd.333.0101.

Authored on

19 mei 2022